Faculty Friday: Jennifer Bean

Deep in a cavernous concrete basement, Jennifer Bean sits stooped over a Steenbeck machine. The large, flatbed editor helps her hand-control the frame-by-frame movement of a filmstrip nobody has seen in eighty years. Like all filmstrips produced before the mid-century introduction of acetate safety stock, it is made of nitrocellulose, a highly flammable material prone to disintegration and spontaneous combustion that shares a similar chemical composition to gunpowder.

“When nitrate begins to deteriorate, it can look like bubbles or gassy layers or a perforation,” Bean says. “But there are still times I have this sense, this feeling, that I can still see what’s under it, when, in fact, you can’t.”

Fleeting figments on early film stock frustrate Bean—a vexation augmented by her “sense of a history evaporating and deteriorating” before her very eyes. Recovering what remains of the fraction of surviving films produced during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and slowly piecing parts back together is all Bean can do.

But Bean—who the Seattle Times once heralded as knowing “more about silent films than Stephen Hawking knows about physics”—does it better than most.

The associate chair of Comparative Literature and Director of the Cinema and Media Studies programs at the University of Washington, Bean traces her archival work with silent films to the 1979 discovery of more than 500 reels of silent film buried in the cold-packed tundra of Dawson City, a remote Canadian town near the Arctic Circle. With little else to do in the wilds of the Arctic during the first decades of the 20th century, the 75,000-person Gold Rush town binged on reels upon reels of early movies, each no longer than 15 minutes. Bean explains how, years later, as the films’ popularity waned, the Dawson City Chamber of Commerce “dug a hole, threw the films in—just buried them.”

However, the dark, freezing conditions were ideal for the preservation of nitrate film, which otherwise acquires a “gummy, almost tar-like” quality as it begins to decompose.

The discovery was, quite literally, a case of the past reemerging to tell a story of how the present came to be. Since then, Bean, whose interest and specialization in early film emerged from a dual-track Ph.D. in American Literature and Film Studies at the University of Texas-Austin, has “never looked back.”

Over the last two decades, her investment in silent-era film preservation and restoration has led to her advise the Women and Film History International Project, the Thanhouser Film Company Preservation, Inc., Turner Classic Movies, and the National Film Preservation Foundation.

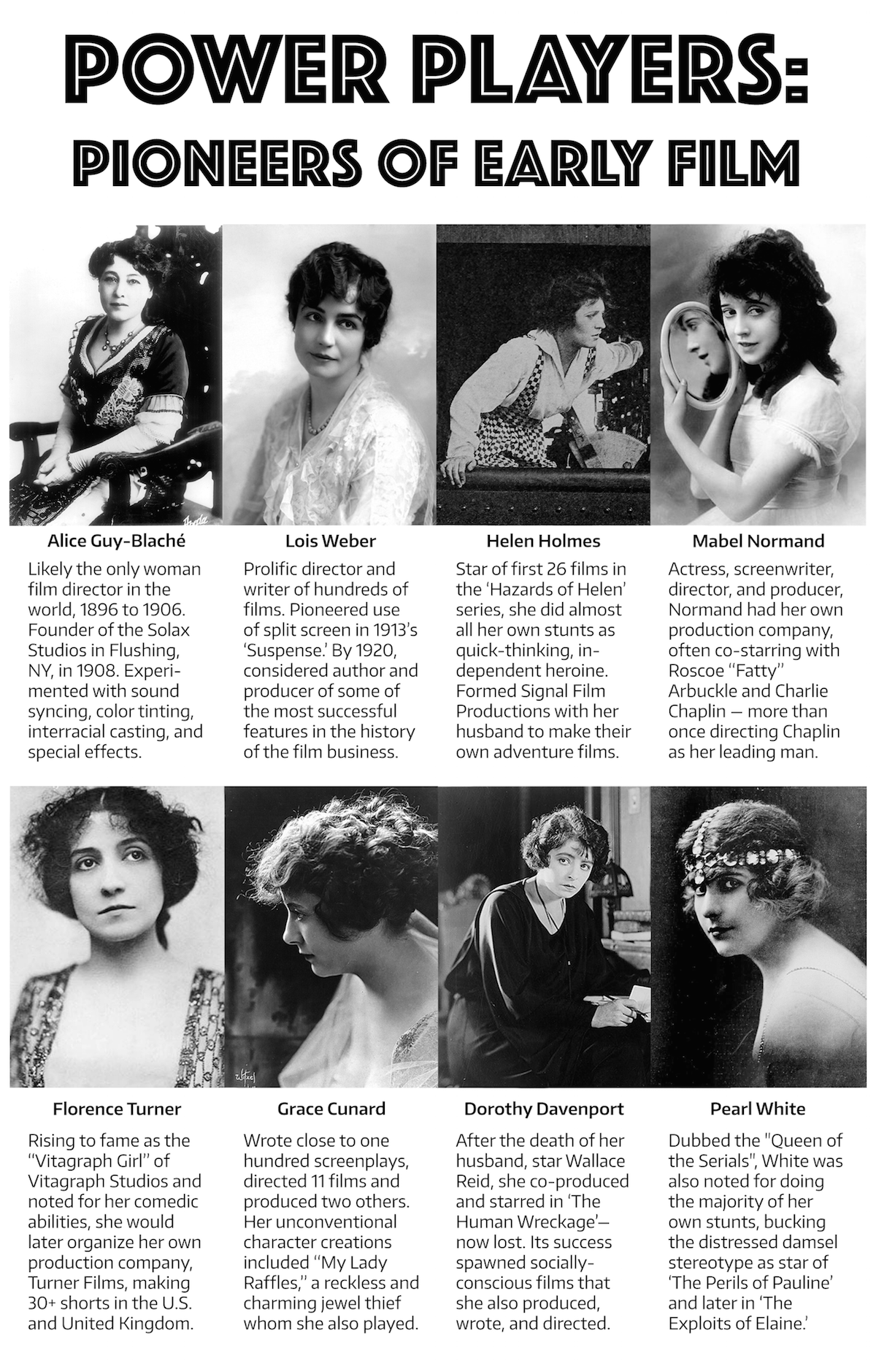

She also helped found The Women Film Pioneer Project, a richly appointed, freely accessible digital encyclopedia spotlighting the hundreds of women who worked behind the scenes in the silent film industry. “They were not just actresses,” the site declares, but also worked as producers, directors, co-directors, scenario writers, scenario editors, camera operators, title writers, editors, costume designers, and exhibitors.

“What we’re working to do with this international collaboration is to list where we’ve seen prints of films, if we know a given individual is involved with the film, and if we think it’s lost,” Bean says. “It’s astounding what still surfaces—and what is still in archives, unlabeled and deteriorating.”

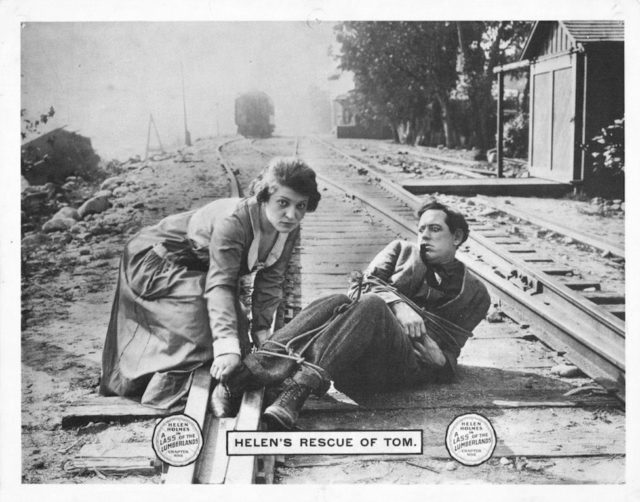

At 119 episodes, each lasting about 12 minutes, ‘The Hazards of Helen’ is believed to be the longest film series of all time. Over the course of the series, four actresses played Helen—a character whose independence and ingenious solutions to often dangerous predicaments upended the common trope of “damsel in distress.”

Silent cinema—perhaps better defined as early cinema—spans a period ranging from 1893 to 1929 in the United States (and up to a decade longer elsewhere). However, of thousands of films produced during that span, less than 20 percent are estimated to survive. There is likely another 10 percent that only exists in pieces and fragments, Bean says, but then it’s a matter of tracking down, identifying, and preserving reels that, due to early mass distribution, could be hidden anywhere from Hoboken to Hong Kong.

Several years ago, Bean salvaged from a Moscow archive of films that once belonged to seminal Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein reels comprising House of Hate, a 20-part 1918 spy thriller starring Pearl White, an actress known for her portrayal of plucky heroines and doing the majority of her own stunts. But fully intact reels are hard to come by.

While working on preservation of another early film series, The Hazards of Helen, whose 119 installments over the course of three years make it the longest film series of all time, Bean struck a dead-end when she discovered the second half of one reel was damaged and missing—dashing her hopes of ever knowing the daring denouement of a 1915 episode, The Escape on the Fast Freight.

But several years later, in a rare stroke of luck, the missing half turned up in an Italian archive, allowing Bean to complete the restoration and conclude a stunning action sequence in which the hard-nosed Helen wrangles robbers from atop of a moving train before tumbling off a bridge with one in her clutches to continue the fight in the waters below.

But for every fortuitous find, there are countless other lost films fading from existence—the stories of those involved in their production disappearing along with them. “There’s so much there that’s overlooked,” Bean says.

Pioneers preserved

21st century digital editing and preservation technology stands as a potential means of salvaging these at-risk histories. This weekend, Bean is coordinating “Sound and Images: Video Essay Workshop,” which will train film scholars in new forms of digital scholarship that utilize the language and form of audiovisual media to critique it.

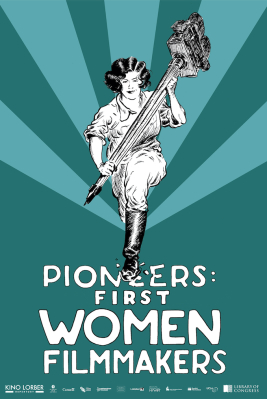

Out in November, “Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers” will bring together dozens of Bean’s film restorations.

The workshop is led by visiting faculty Jason Mittell of Middlebury College, who first developed it with National Endowment for the Humanities funding in 2015.

Hosted on the Seattle campus by faculty from all three UW campuses, including Bean, David Coon of UW Tacoma, and Lauren Berliner of UW Bothell, the 20-spot workshop is already full with 8 PhD students and 12 faculty, but the public lecture on Friday at 4pm is open to all.

“This type of video essay workshop allows scholars and teachers to explore their object of study from the inside out,” Bean says. “Audiovisual editing skills are increasingly essential to the profile of any cinema and media studies scholar. We’re training ourselves so we can train and facilitate undergraduates’ ability to harness the tools of editing software.”

Bean says her hope is that the workshop will illuminate students’ vision for what’s possible as a filmmaker and film scholar in college, but that it will also serve as a catalyst for the next steps in her own preservation work.

“Part of my personal impetus to become involved in videographic criticism is to take prints and digitize them and put them together in a new form,” Bean says, alluding to her ultimate goal of building a digital home for thousands of film fragments as well as feature-length composites that can bring films once on the verge of being lost forever back into the public eye.

“I want to train myself to capture what remains from the archives and reproduce it in digital form in new ways for people to see,” she says. “If you have something to restore that doesn’t look like it could be projected in a theater, it can be difficult.”

In November, Kino Lorber, a major distributor of early films, will release Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers, which brings together dozens of Bean’s restorations of the work of early film pioneers, including Alice Guy-Blaché, Lois Weber, Helen Holmes, Mabel Normand, Grace Cunard, and Dorothy Davenport Reid, who thrived as directors, writers, and producers—all “before Hollywood hardened into an assembly-line behemoth and boys’ club.”

“I want to recover these moments in which women were stepping out into the streets and stepping onto the screen and behind the camera and mobilizing as one of the many factors that led to women’s right to vote and the ratification of the 20th amendment,” Bean says.

The New York Times dubbed the release “a corrective to our collective amnesia,” and “a thrilling look at the variety of films made by women, most before they won the right to vote. But, for Bean, Pioneers: First Women Filmmakers and collections poised to follow it are as much about looking to the future as they are about looking to the past.

“Although a lot of what I work on may seem like just entertainment—these are comedies and early action movies—it’s women doing this real, physical work and showing people that they are capable of doing things, thinking things, and making things that had previously been prohibited or considered unimaginable,” she says. “Real change is possible and I like to imagine that our future could be different just as it was imagined at that time.”

Dive into the action-packed cinematic past with this Whole U primer on how to navigate UW’s Silent Film Online Database.

Jennifer Bean holds a B.A. from Davidson College and an M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Texas-Austin and has published widely on silent-era cinema, including recent collections, Silent Cinema and the Politics of Space, Flickers of Desire: Movie Stars of the 1910s, A Feminist Reader in Early Cinema, and a special issue of Camera Obscura on “Early Women Stars.”

Her voiceover on various restored films from the early period of cinema can be heard on two DVD-anthologies, More Treasures from The Film Archives (2004), and Treasures III: Social Issues in Early American Cinema (2007). She is currently at work on two books, Junking Modernity: Early Cinema, Globalization and the Question of History and Uncertain Feelings: Feminism, Affect, and American Cinema, 1907-1927.