Faculty Friday: Rob Turner

Rob Turner has a message for his fellow teachers: A watered-down syllabus is a good thing.

Students in Turner’s class explore the sweeping role of H2O. “It’s about how water moves around the globe — in the natural cycle, but also via trade and commodities,” said the UW Bothell senior lecturer.

You’d be surprised how much water is in everything around you. Those 20-minute showers are lavish, but how much water did it take to make your favorite pair of shoes? How about the beans in your morning coffee? The fuel in your gas tank?

Water that goes into producing consumer goods is called virtual water, and it flows through your closet, your kitchen, and your daily commute. Virtual water accounts for over 95% of our water footprint, according to estimates by National Geographic, but we don’t talk about it much. Turner wants to change that.

He teamed up with the InTeGrate program, which is funded by the National Science Foundation, to create a module for his class BIS 392: Water and Sustainability. Starting this fall, teachers around the country will be able to bring Turner’s lessons into their classrooms.

What’s So Great About Water?

In developed countries, people tend to overlook water issues because they don’t have issues finding water. But more than a third of the world’s population lacks reliable sanitation, and 800,000 children under 5 years old die from diarrhea each year. On a systems level, global water scarcity can cripple industries, spark social unrest, and ignite civil wars.

Reliable access to water builds strong economies. Between 1760 and 1840, water-based steam power fueled boats, railroads, and textile factories, enabling a period of large-scale mechanization and production known as the Industrial Revolution. Crops grew on fertile land, harvested by slaves or cheap labor.

Today, developing countries are hamstrung by comparison. Their access to water is often curbed by natural disaster and drought, and they must be diligent about how to invest their limited supply. “Historically, and still to this day, it’s mostly used for agriculture,” Turner said. “But that’s not the most efficient way to foster economic development — the kind that the developed world has enjoyed.”

That’s why some countries redirect their water from agriculture to industry. This shift requires importing food and gambling on the new economy to pay the tab. Venezuela, a country that turned away from agriculture to develop oil, provides a case study of the risk involved. “When oil prices plummeted over the past year, their economy collapsed, and they are suffering from severe food scarcity,” Turner said. “Their decision to stop producing the bulk of their food and rely on imports is having a devastating impact on their citizens.”

Developed countries are also feeling the heat when it comes to water scarcity.

“The multiple-year drought in California put a lot of the United States on notice,” Turner said. “This is not a problem you can just brush off.”

Where’s Your Water Source?

California isn’t alone. Drought has spread through the Southwest and up to Oregon and Washington. Governor Jay Inslee declared a statewide drought emergency in 2015, but those of us on the west side of the mountains might not have noticed. “We mostly avoided repercussions since our reservoirs were in good shape,” Turner said. Drive over into Yakima Valley, though, and it’s a different story. “Too many users, not enough water to go around.”

That’s not to say Puget Sounders are in the clear. We’ve been getting less and less snowfall in the mountains. That snow melts down into rivers as a freshwater supply — our “bank” in the drier summer months.

If you didn’t know that, you’re not alone. Turner says most of his students don’t know where their water comes from, or where it goes when they’re finished with it.

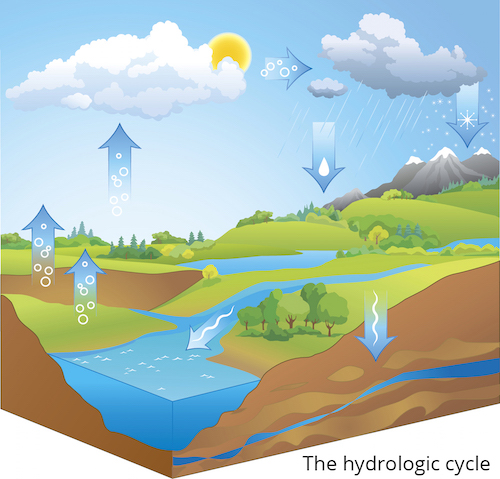

As simple as it sounds, the answer to the first question is “from the sky.” As any TV show based in Seattle will remind you, it rains a lot here. That rain pours into our rivers and reservoirs, then gets filtered, treated, and piped to your home. The Chester Morse Reservoir, depicted in the top right of this diagram, supplies most of the water for the Seattle region.

When we flush our toilets, the water flows to a wastewater treatment plant (the same place that factories send their water). The disinfected water is then recycled or sent back into the Puget Sound, where it eventually evaporates back into the sky. This is the hydrologic cycle.

Drive Down Your Water Footprint

Turner has students track their virtual water consumption with a water footprint calculator (here’s one made by National Geographic). The calculator tracks the water you consume in your home, your diet, your car, and your trips to the mall.

“In most cases, you’re going to find that your water footprint is way above the global average,” Turner said. “We live a very water-intensive lifestyle, and we take it for granted that this is the norm. But if everybody lived like we did, there would not be enough water to go around.”

The state of our water supply should guide our water use. Shorter showers in the morning? Sure. Faucet off when you brush your teeth? No reason not to. These are good habits, Turner says, but they probably shouldn’t be your priority. “A more impactful decision you make is the products you buy.”

The best thing you can do is shop from local sources, since imported goods drain the water supply of other countries (add that to your list of ethical dilemmas). Cotton production in Uzbekistan, for example, helped dry up the Aral Sea. “It doesn’t make sense for us to get cotton from deserts,” Turner said, “but we do.”

And then there’s meat. Livestock has to eat, and what they eat has to be grown. Here’s the rub: Over 300 gallons of virtual water go into a single serving of beef. Another 100 gallons go into a 3-ounce slice of pork, and 88 more are in a piece of poultry. By this math, an average American eats 3,600 gallons of water each week.

“It’s pretty hard for us to justify,” Turner said. “From an environmental analysis, it’s not very sustainable.”

In this sense, a locally sourced plant-based diet does wonders for your water footprint: You eat the food that the livestock would eat, instead of eating the livestock that eats the food. Crops also need water to grow — 27 gallons of water make a 3-ounce serving of corn — but meat needs exponentially more.

What’s a card-carrying carnivore to do? When possible, opt for chicken and fish instead of their four-legged friends (this can also improve your heart health). Whichever meat you eat, buy local. Trucks, trains, and cargo ships need fuel to move, and 13 gallons of water go into each gallon of gasoline.

As with anything, start small. Try shopping at a farmer’s market, carpooling when you can, or giving up meat one day a week. “When I go to Subway, I get the veggie patty,” Turner said with a chuckle.

A Multilayered Guy

Turner is a marine geologist by training, but he talks about economics a lot. And politics. And social issues. His wide-ranging teaching style made him a great fit for UW Bothell, which prides itself on blending disciplines. He joined the campus in 2006.

“You get to make up what you want to teach and learn while you’re doing it,” Turner said about teaching at UW Bothell. “If I would have taken a position at other places I interviewed, I would be teaching the same disciplinary geology courses over and over again, which would get pretty darn stale.”

Outside of the classroom, Turner has spent years tracking water quality with students. He’s currently researching UW Bothell’s famous crow population, which totals 15,000 birds in the winter months. These crows are known to leave behind waste, which is full of both nutrients and pathogens.

Turner and his team have found high rates of E. coli bacteria in the nearby North Creek Wetlands. In the lab, they’re experimenting with mushrooms that can soak up these pathogens. By running wetland streams through wattles that have been inoculated with these mushrooms, Turner thinks they might be able to counteract many of the pathogens. “If it’s successful, we can live with the crows instead of shooing them off.”

As for Turner’s off-the-clock habits — well, this one sounds like the back of a Laffy Taffy. What does a geologist do in his spare time? Plays in a rock band. “It’s a wonderful creative hobby,” he said. “I don’t do sudoku — I write songs. They’re like puzzles that I solve.”

His research occasionally streams into the music. One of his songs is about sustainability. Another tackles liberal-versus-conservative animosity. But mostly, he admits, it’s the usual stuff: “Songs about love, or lack thereof.”

Turner has a B.S. from Allegheny College, an M.S. from Western Washington University, and a Ph.D. from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He also teaches geography, environmental science, and environmental monitoring.

4 Thoughts on “Faculty Friday: Rob Turner”

On July 15, 2016 at 9:18 AM, Marilyne Cunnington said:

What a fascinating, educational, interesting article, with a bit of humor added, which I enjoyed. Loved reading it and it pointed out some real hard facts about water usage I was not aware of………Thank you!!!

On July 15, 2016 at 11:52 AM, jay said:

I’m glad to see meat mentioned! 🙂 I think if more people knew how many resources meat farming uses, more people would choose to eat a lot less meat. (It was definitely a surprise to me.)

On July 15, 2016 at 1:57 PM, Rebecca said:

Seeing the evaporation of the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan, and running the numbers on my virtual water use through the National Geographic water calculator certainly augmented the great interview with Rob Turner. Nice work and thanks for the these links!

On July 21, 2016 at 9:59 AM, Sebastian said:

Oh my gosh what a stud! And I know him, too!

Comments are closed.