Faculty Friday: Alexes Harris

For any academic, the moment of holding your first published book is one of accomplishment, elation, and total triumph. But for Alexes Harris, a professor of Sociology at the University of Washington, that moment came on the heels of learning her life hung in the balance.

For any academic, the moment of holding your first published book is one of accomplishment, elation, and total triumph. But for Alexes Harris, a professor of Sociology at the University of Washington, that moment came on the heels of learning her life hung in the balance.

A year earlier, she’d been working out when she sensed something wasn’t right.

“I started having what felt like asthma attacks in the indoor cycling class, so I went to see my primary care physician,” Harris says. “It took a year from lab work to seeing cardiologists and allergists before an hematologist at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance eventually said, ‘Let’s do a bone marrow biopsy.’”

That was May 2016.

“He called me the next night and said this is serious and set up an appointment with a doctor,” Harris recalls. “Then he called me again on a Thursday when I was preparing to go present at the Southern Poverty Law Center in Alabama.”

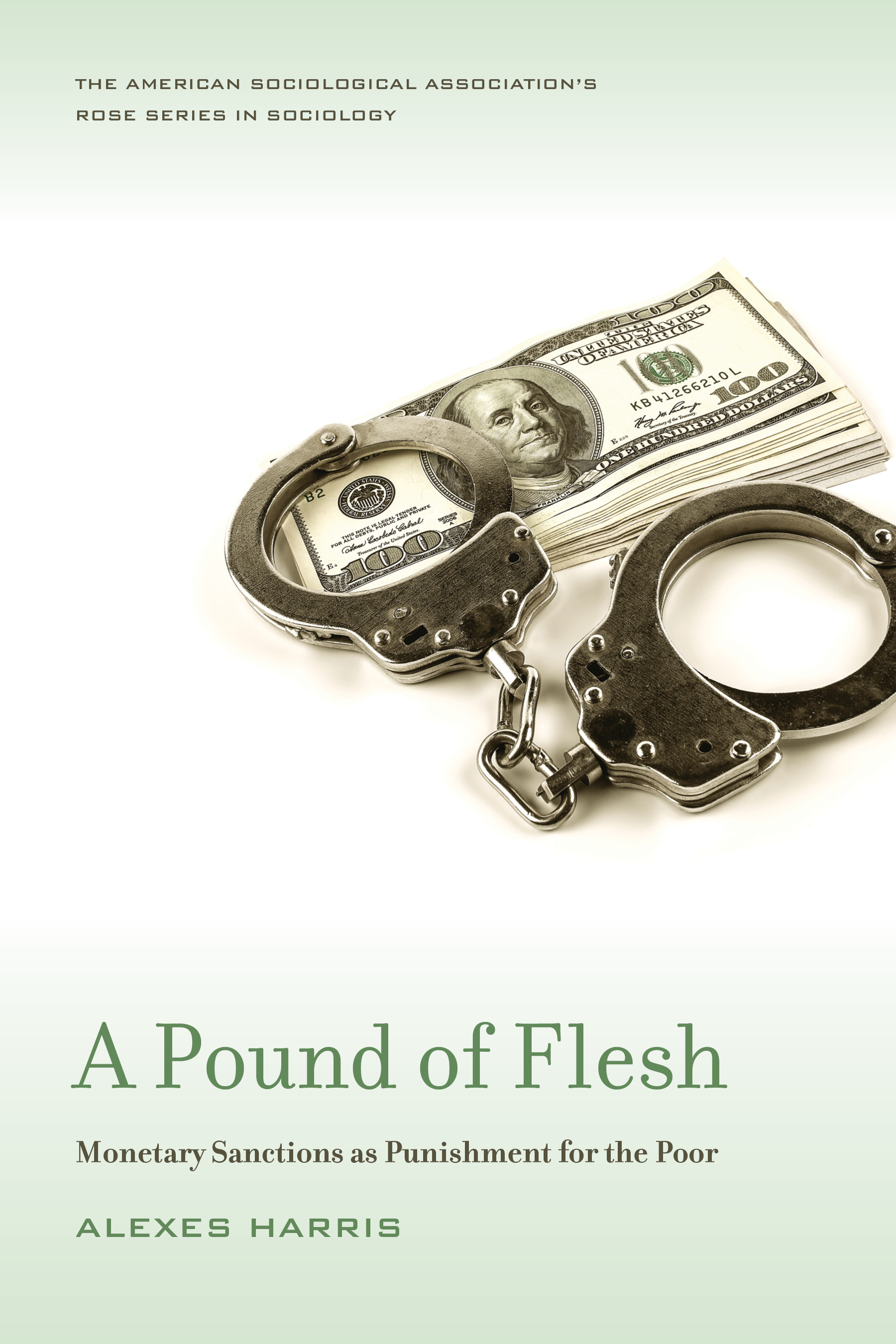

The impending trip stood out as Harris’ first chance to see the hardcopy of her book, A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. The SPLC had ordered 100 copies. She asked her doctor if she could still go.

Drawing on legal precedent, state practices, and in-depth interviews, “A Pound of Flesh” uncovers the ways in which unpayable legal debt becomes a source of permanent punishment for the poor in encounters with the criminal justice system. It debuted fewer than three weeks before Alexes Harris began intensive chemo therapy for myelodysplastic syndrome, a rare form of blood cancer.

“He said I think physically you’ll be fine, but I think he was like, ‘Do you mentally get what I am telling you?’ I knew that, but also knew this was going to be the first time—and maybe the last time—I could talk about my book too.”

She decided to make the trip, but it wasn’t easy.

“It was surreal because the symptoms were getting worse, so I was really, really tired,” Harris remembers.

“I had actually taken the afternoon and went to my hotel room on that Monday to take a nap when my doctor called me and said I was probably going to need a marrow or stem cell transplant.”

Tuesday morning came. Harris grabbed a copy of her book, gave her talk, and took an early flight home.

“At least I got to hold my book and sign a couple copies, which was neat,” she says. “Then, that Thursday, May 26, 2016, I got the full diagnosis.”

Harris learned she had myelodysplastic syndrome, a rare blood cancer.

She was told that if she did not begin treatment right away, she would have about 18 months to live and that she needed to take at least a year off in order to receive treatment that would put the cancer into remission. Only then would an attempt at a transplant be possible.

“My book came out June 9th, we celebrated my daughter’s birthday on June 26th, that Saturday, and then on Monday, I went into the hospital and got a port put in my chest and had intensive chemo for a week.”

Everything else in Harris’ life had to be put on hold—including her work as the principal investigator on an eight-state, multi-year study expanding on the work she’d chronicled in her book on the criminal justice system’s sentencing system of fines and fees.

The $4 million grant-funded project, then only a year underway, would have to wait, along with everything else. “The post-docs and graduate students here kept everything afloat,” Harris says. “Once I was told I had 18 months to live and needed a transplant, I knew that this was going to be a tough road.”

“Devastating” disparities

But things were about to get even tougher than Harris could have imagined. Initially, she had assumed she would be able to easily find a marrow donor match with her twin brother.

When it turned out he wasn’t a match—only 30% of the patients who need a transplant are able to find a donor who is a perfect match within their own family—Harris realized she was going to have to rely on a stranger to save her life.

In the U.S., more than 14,000 people’s only chance of survival is a marrow or stem cell transplant from a complete stranger.

Be the Match, the nation’s largest marrow donor registry, identified two other listed individuals as a potential match on the registry, but both declined to move forward in the process as donors. Then, a third match turned up—cause for a brief flicker of hope. But because of the blind search process, Be the Match didn’t realize that they had found Harris as a potential donor for herself.

She had registered twenty years prior as an undergraduate at the UW. The news of that “match” was proof of the donor registry’s pinpoint accuracy, but disheartening all the same.

“It was a horrible feeling,” Harris recalls.

“It was devastating when I found out my brother wasn’t a match; devastating when I learned two people weren’t going to do it; devastating when, for a second, they thought my 20-year-old self could save my 40-year-old self.”

She immediately started to research how matches were found and discovered finding a non-related, full match can be exceedingly difficult if you are a person of color—especially one of mixed ethnicity—because fewer such individuals are represented on the donor registry. Harris’ heritage is African American, Filipino, and Caucasian.

For one whose work focuses on social stratification processes and racial and ethnic disparities, it was a bitter irony.

Tangible transformations

While Caucasians have a 75% chance of finding a full match in the existing marrow registry, African Americans only have a 19% likelihood of finding a match and comprise only 7% of the United States registry.

Within the U.S. registry, the likelihood for finding a full match is higher for people of Mexican (37%), Chinese (41%), South Asian (33%), Hispanic Caribbean (40%) and Native American (52%) ancestry than for African Americans, but still significantly lower than for Caucasians.

Eventually, Be the Match identified a mismatch for Harris via donated umbilical cord blood.

It wasn’t perfect, which meant it would present its own risks during the transplant process, but Harris decided to move forward with the alternative stem cell transplant procedure anyway.

In September 2016, she received a transplant using cord blood. It was successful and her cancer is now in remission. And while Harris still has manageable chronic issues due to the inexact nature of the match, what matters, she says, is that she’s alive—and now more determined than ever to make a difference.

“I knew that I had an opportunity to raise this as an issue,” Harris says. “I told everyone I’m not going to die from this, but in my mind, I didn’t know if I was going to die. And I felt like if I was going to die, I didn’t want to die for nothing. This had to matter and mean something.”

Before finding her partial match, Harris’ friends organized registry efforts in her name in Seattle, Houston, New Orleans, two in New York, as well as one in Washington, D.C. in concert with the Department of Justice.

“If that meant we could have registries and get people and save one life—even if it was somebody else’s—then why not try?”

“I teach about disparities in education, criminal justice and health, and we feel overwhelmed and frustrated with the lack of changes [in these areas],” she says.

“I want people to know that registering to donate marrow or asking your friends to register is literally one thing we can tangibly do toward saving lives. If you register, you are directly changing the landscape of health inequalities.”

Pioneering partners

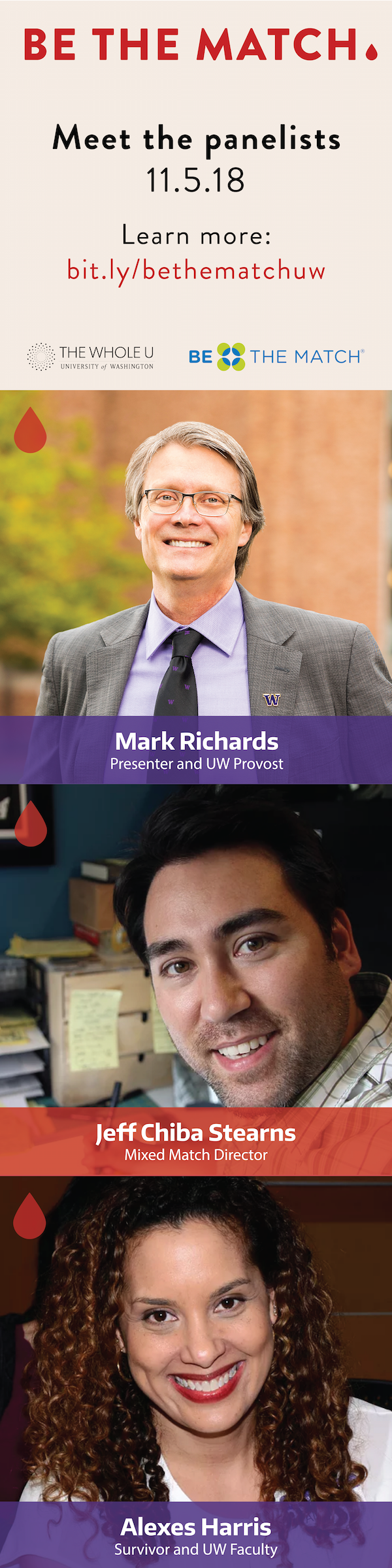

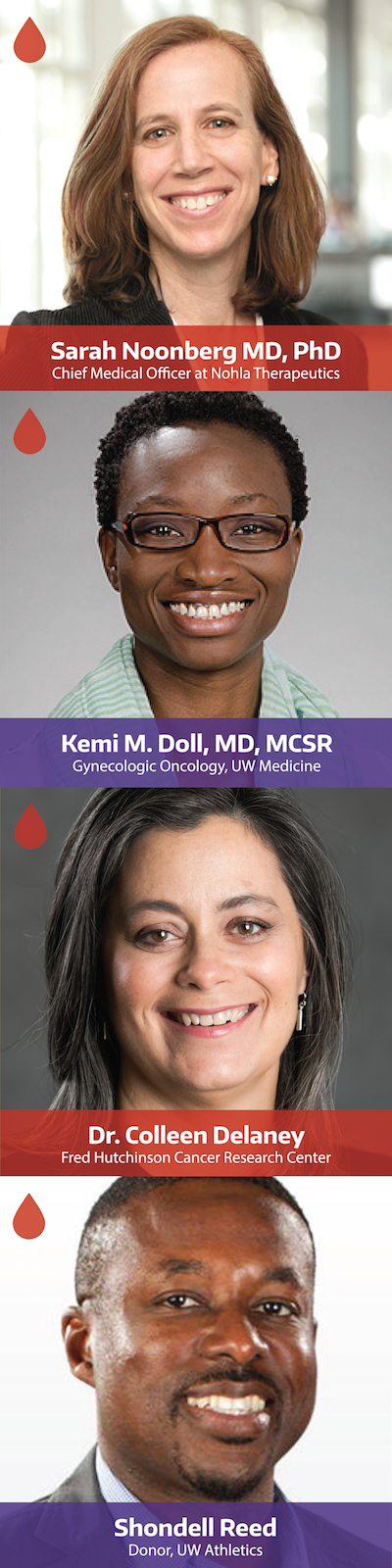

Harris’ efforts will take on a new dimension on November 5, when the University of Washington and Be the Match officially launch a first-of-its-kind partnership with a documentary screening and panel event at the HUB.

Hosted by The Whole U with an introduction from Provost Mark Richards, the kickoff will feature six panelists, including Harris, doctors from UW Medicine and Fred Hutch, and a marrow donor, Senior Associate Athletic Director Shondell Reed.

“The more we tell these stories, the more people will want to do something,” Harris says. “Once we come out and announce this partnership, my hope is other universities will follow suit.”

Over the next two years, the UW and Be the Match aim to raise awareness of the disparities in donor representation and register 2,500 diverse individuals from the UW community in the process. The partnership has the potential to save the lives of at least five people who otherwise would not be able to find a match.

For Harris, the partnership presents a chance for students, faculty, and staff to realize their greater potential as global citizens.

“I think this is one opportunity where we don’t have to feel helpless,” Harris says, citing that there are now more than 80 diseases that can be cured with a marrow or stem cell transplant.

“What better way to be connected to people around the world?”

For people of color fighting for justice and greater equity in society at large, Harris says registering can serve as an act of solidarity and intersectionality that draws people together in common—demonstrating the power of valuing lives and representing a step in the direction of joining together to address other broader issues, such as state-sponsored violence and reform of the criminal justice system.

“This gives people an opportunity to be a superhero and help—particularly if you’re a person of color,” Harris says. “It’s one thing we have to do for ourselves, by ourselves as communities of color—nobody else can do this part for us.”

Only 1 in 430 on the registry will ever be called upon as a close enough match to donate to a specific patient, but every person who registers swells the chances that ethnically diverse cancer patients eagerly awaiting a match will find one.

While the issue of diversifying the nation’s largest marrow registry now goes beyond Harris’ own need, the fact that she was able to beat cancer and still be here today means the world to her—both personally and professionally.

“I have a son who’s seven, a daughter who is 11, a husband, and I think I do important research that contributes to our society,” she says. “I teach at least 600 students and, without my transplant, I would not be here doing that work. So that matters.”

Harris is now in year four of her five-year, eight-state study of systems of monetary sanctions. By the end of December, she and her fellow investigators will have concluded their data collection phase, which includes observations of sentencing and sanctioning hearings as well as interviews with more than 700 people who can’t afford to pay the average $1,200 fine for a felony conviction. As a result, these individuals are often re-incarcerated, incurring what can become a lifelong debt that effectively tethers them to the criminal justice system. Within a year’s time, Harris hopes to publish the study’s findings in full.

“Inequality in general is something that ruffles my feathers,” she says. “I got into academia not solely to write journal articles or books that are going to sit on shelves, but really to try to engage with and inform public policy. I have no shyness about that. I really want my research to matter in a way that could help inform changes that could benefit people who are poor, people who are of color.”

As a survivor of cancer who benefited from a stem cell donation, Harris says whatever positive implications born of her ability to continue her research are a direct beneficiary of peoples’ willingness to register and donate marrow and stem cells.

“You’re not giving me something material or frivolous. You’re giving me my life.”

Harris, whose donor was a newborn, wonders if that parent knows the impact their decision to donate the umbilical cord had on her life and the lives of everyone around her.

“That parent could raise that child saying the day you were born, you saved someone’s life. That’s just amazing to me and I wish more people would feel that way.”

“Can you imagine if you saved someone’s life? Very few people can say that.”

On November 5 from 5:30 p.m. – 7:30 p.m., we invite you to join the UW community in the HUB South Ballroom for a Be the Match Kickoff Event to explore the essential need for multiethnic donors worldwide. Doors will open to this free event at 5 p.m. for light refreshments with a welcome and introduction from Provost Mark Richards. Learn more here.

One Thought on “Faculty Friday: Alexes Harris”

On October 22, 2018 at 3:43 AM, Barclay said:

Way to persevere Professor Harris. Glad you are still with us through all of your obstacles.

Comments are closed.