Faculty Friday: Josh Reid

On May 17, 1999, nine members of the Makah tribal nation paddled a canoe into the waters off Cape Alava on the Olympic Peninsula in pursuit of a 30-foot gray whale. From the first harpoon strike to a finishing shot delivered by a specialized rifle, the hunt lasted no more than ten minutes, but kicked off an international debate on the meaning of sovereignty and the nature of history that has roiled waters of public opinion ever since.

Opponents of the hunt questioned whether it was right to kill whales to keep a longstanding cultural practice alive, while supporters of the Makah hunters asked how treaty rights of a sovereign people could be subverted in favor of preserving what might amount to a few whales each year. Newspaper editorials called for the culture to “evolve,” while animal rights activists threatened to disrupt any future sojourns by the Makah to hunt on the open sea.

Josh Reid, now an associate professor of History and American Indian Studies at the University of Washington, was teaching middle school in 1999 when it all went down.

“One of the things that really struck me was that even supporters and opponents seemed to agree that Makahs were whaling because they wanted to live in the past,” he recalls. “Those who supported Makahs said, ‘Well, we’ve screwed them over [in the past], so let’s let them have this life in the past if this is what they want,’ while opponents said they need to modernize and used far more racist rhetoric than that.”

Makah man in a canoe getting ready to harpoon a whale off the coast of Washington (Photo: Asahel Curtis – University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections)

As an undergraduate at Yale, Reid had written his senior thesis on the politics surrounding fishing rights in Washington State. When the debate over the Makah whale hunt flared in 1999, both he and his class of middle school students were electrified.

“Students get fired up by incidents of justice and injustice. Not much more shows you a sense of this disconnect over intent and how things actually play out than the adjudication of treaty rights over time,” he says.

The issue’s complexity was—and is—a product of the Makahs’ own unique place in the history of the Pacific Northwest.

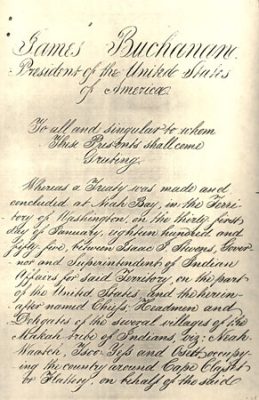

The only tribal nation in the lower 48 states of the United States with a treaty that expressly guarantees them the right to whale, the Makahs voluntarily suspended whaling activities in the 1920s when commercial whaling drove gray whales to the brink of extinction. But by 1994, the populations had rebounded to the extent that the gray whale was removed from the endangered species list. Shortly thereafter, the Makahs announced their intention to reactivate the hunting rights assured them by the Treaty of Neah Bay.

The Treaty of Neah Bay was ratified by the U.S. Senate on April 18, 1859. At its signing in 1855, one Makah chief informed negotiators, “I want the sea. That is my country.”

As part of the 1855 treaty signed by Governor of Washington Territory Isaac Stevens and leaders and delegates of the Makahs, the Makahs reserved for themselves the rights “of taking fish and of whaling or sealing at usual and accustomed grounds,” while also extending these rights to whites “in common.”

“It flips on its head the usual narrative that we have on American Indian history that tribal lands and resources were shared in common by those particular peoples [and] then the nation state came in and turned it into individual units,” Reid says. “That is indeed the opposite of what happens for Makah marine waters.”

Thus, the 1999 hunt was simultaneously a moment of supreme cultural significance that saw the Makahs reassert sovereign rights over the waves and nothing new—simply the latest outing onto the open sea in a whaling tradition that stretched back nearly 2,000 years.

“In a nutshell, these are the people of the sea,” Reid says. “They are tied to the ocean. It’s why they call themselves Qʷidiččaʔa·tx̌ (pron. kwi-dihch-chuh-aht), meaning People of the Cape. They are whalers, fishers, they caught seals—and have for thousands of years.”

Contrary to what Reid sees as the prevailing public discourse, the Makah Nation’s reassertion of whaling rights in their customary grounds off Cape Flattery wasn’t some bid to cling to or reclaim a lost past; it was a step toward revitalizing Makah culture for generations to come by reestablishing long-standing relationships with the sea and its marine life.

For centuries, the Makahs (a name conferred by the neighboring S’klallam people, meaning “generous with food”) enjoyed a regional hegemony based on their dominance over the Strait of Juan de Fuca and prowess in harvesting halibut, seals, and whales, whose byproducts they’d trade in great quantities with neighbors on the Olympic Peninsula and Victoria Island. Whale oil was particularly valuable in this exercise of economic imperative.

When the first non-native ships began arriving in the late 18th century, the Makahs’ prominent position and economic self-sufficiency extended them a greater degree of independence in dealing with the new arrivals and uncommon agency in charting their own path forward.

The Makahs’ singular relationship with and political and economic dominance over the sea forms the subject of Reid’s first book, The Sea Is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs.

The first full-scale history of the Makah people from the arrival of maritime fur-traders in the eighteenth century, the book uses history as a precedent to challenge and debunk standards of “realness” that hold native peoples’ “authenticity” hand in hand with living in a technological and cultural past. In doing so, it illustrates the under-sung influence the Makah Nation had in shaping the maritime economy of the Pacific Northwest.

Even as more Europeans and Americans arrived to the region, Makahs were able to leverage their mastery over the waters and resources therein to simultaneously resist assimilation and embrace modern opportunities and technology on their own autonomous terms. By the eighteenth century, Makahs were enjoying products made in Europe and China, while tenaciously resisting the colonial inroads that often accompanied such commercial exchanges elsewhere.

The recipient of four major awards since it was published in May 2015, The Sea Is My Country found its genesis in those initial conversations Reid had with his middle school history students back in 1999.

“That’s where things came together and I realized this was something that would be worth my time and be important to somebody else—i.e. the Makahs,” Reid says.

But even before the whale hunt or the electrifying classroom discussions that followed in its wake, Reid’s own personal history was on a collision course with the one he would later write. A member of the Snohomish Indian Nation, Reid grew up in Olympia, where he played Cajun violin in a band called Slide One Bayou. He used to go camping with his grandfather on the Olympic Peninsula, just south of Cape Flattery, where he’d listen to his grandfather tell stories over a driftwood fire of learning to fish from his mother and grandmother near Port Angeles.

“I always kind of thought of how native peoples had this relationship with the ocean; that it was more than just this connection to the land,” Reid says. “Even if I really couldn’t articulate it beyond the stories my grandfather would tell.”

Years later in the late 1970s, his parents took him on a backpacking trip near Ozette, Washington, where an old Makah village buried in a landslide in the mid 16th century had recently been excavated, revealing a trove of valuable historical artifacts.

“Makahs knew the village had been there, but what the excavation did was confirm all the stories the tribal nation had told about their practices on the ocean,” Reid says. “From the Makah perspective, there was no doubt—they knew this—but from an outside perspective, there’s long been a tension between oral histories and what constitutes historical evidence.”

The hard archaeological evidence from the Ozette dig bridged a divide between the practices of “academic” history and how history is constituted from the perspective of native peoples. The sheer scope of the site and all it contained proved the “magnitude and longevity” of Makah practices once and for all.

Makah cutting up a whale, 1910. (Photo: Asahel Curtis – University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections)

“There were so many whales being hunted and processed, it was more than that community there at Ozette could consume, which means that those were goods that were traded to neighboring tribes and communities,” Reid says. “Those experiences early on gave me a personal connection and relationship to that part of the Olympic Peninsula.”

“It framed for me this idea that native people have had and have a relationship with the ocean just as much as they have had with the land, which is what you’ll typically learn in a text book.”

In 2003, Reid began graduate work at UC Davis. He toyed with writing a dissertation comparing Makah notions of marine space with those of Maori in New Zealand, with Davis funding two research trips there. Reid says the process helped him shape questions about his research and, if not for the need for extensive Maori language work, he might have crafted a comparative history.

He ultimately chose to focus solely on the Makah, but his graduate work in New Zealand and elsewhere in the Pacific would come to influence projects later on.

In the two years since The Sea Is My Country was published, Reid has embarked on curriculum development work that’s taken him back to his K-12 teaching roots.

“Some of the most, if not the most, important work that I do is in working with K-12 teachers and students and taking all this rich, good work we do as teachers and historians and helping to pull that apart and make it digestible for the larger public,” he says. “Our basic narratives need a healthier dose of American Indian history.”

Reid contends that, instead of using the encroachment of Europeans on native peoples as an entry point to understanding native histories, we should have robust sets of native histories that stand on their own—incorporating U.S. histories into a broader and far-reaching narrative of native peoples at the point of intersection.

From Reid’s experience researching the Makahs and his graduate work in New Zealand emerged a framework of questions that informs what he refers to as his “next big monograph,” dealing with indigenous explorers in the Pacific. In reading captains’ logs from encounters with Makahs, he discovered there were indigenous people from the Pacific Northwest aboard these British ships returning from China.

“They’re often written off as laborers or kidnap victims; their motivations are undercut and minimized and never prioritized,” he says of these returning travelers. “These people were actually looking at what the broader world was like, just like Europeans were doing at the time.”

Through a series of case studies, Reid says he’ll seek to turn history on its head and reevaluate notions of what and who an explorer is.

Makah whale hunters landing their canoe at Neah Bay, 1900 (Photo: Anders B. Wilse – University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections) Explore more historical images of the Makah at the UW Libraries Digital Collections.

“We think we know what exploration is. It’s done by certain types of people for certain purposes, but native people are doing this too. For me, I’m turning that around in talking about native engagement with the making and shaping of the modern world.”

Because each individual case study involves its own set of unique historiographies (such as what did print culture look like in 1780s Canton, China, if any existed at all), the project presents its own set of challenges. But for Reid, it’s all part of the process of beginning to conceive of native history outside of the boundaries of smaller-scale tribal histories—looking for those larger connections wherever water is found.

It might be uncharted territory for an historian, but the trackless expanse of the Pacific never stopped the Makahs or the host of other historical figures who populate Reid’s future text.

For once, at land’s end, history begins.

Josh Reid holds a B.A. from Yale University and an M.A. and Ph.D. from University of California, Davis. A three-time Ford Foundation Fellow, he previously served as assistant professor of history and director of the Native American and Indigenous Studies Program, University of Massachusetts, Boston. Next fall, he’ll teach the course, Indigenous Leaders and Activists. Learn more about The Sea Is My Country here.

2 Thoughts on “Faculty Friday: Josh Reid”

On July 28, 2017 at 11:59 AM, Erin Clowes said:

Great article – inspiring, Josh! Thank you!

On July 30, 2017 at 12:05 PM, David Barr said:

I remember this controversy from reading the papers back then and this gives a totally different perspective–

Comments are closed.