Staff Story: Alysun Deckert

Alysun Deckert knows what it means to run fast. She always has, dating back to high school in Salinas, Kansas where she won nine state championships running cross-country and as a track athlete in the 1600m and 3200m.

Turned marathoner after college, she also knows what it means to sustain performance at the highest levels—not just over the course of a grueling 26.2-mile marathon, but over long periods of time as well: having competed in Olympic Trials for the marathon four times in 1996, 2000, 2004, and 2008.

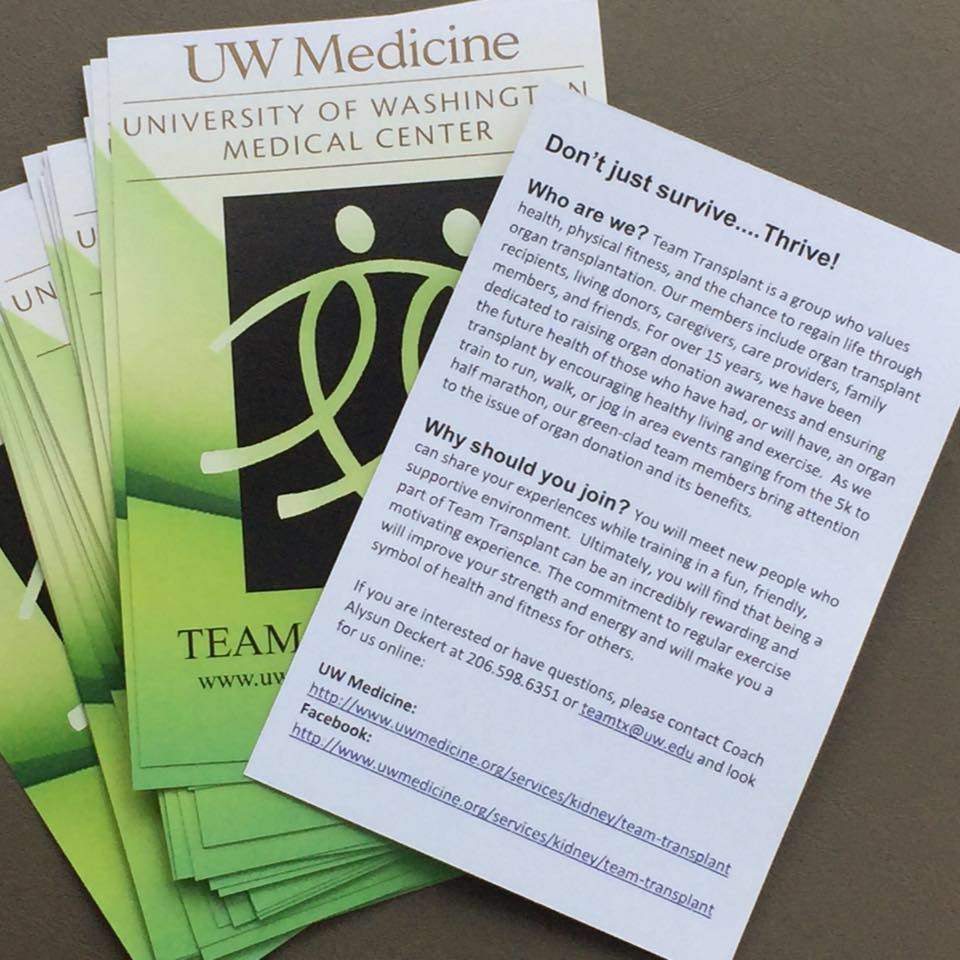

As clinical nutrition manager at the University of Washington Medical Center, she also understands what it means to start all over again. Deckert coaches kidney, liver and pancreas transplant patients back to strength and life—not just from their hospital bedside, but on the footpaths and side streets of Seattle as part of Team Transplant, a comprehensive training and exercise program she helped found in 2001.

“It’s about getting people out and saying, yes, you can exercise, you can go a little farther, you can push yourself a little harder,” Deckert says of Team Transplant, whose goal is to promote fitness as well as organ donation awareness by training for and completing a half marathon in the Greater Seattle area. “I thought, instead of doing something in honor of them, let’s get them to be the participants.”

The group consists of UWMC staff, transplant recipients, their friends, family members, and donors and has grown from an initial 35 members (of which five were transplant recipients) in 2001 to more than 180 participants (of which approximately 30 are transplant recipients) today. For Deckert—who also serves as a clinical instructor in the School of Public Health—Team Transplant provides a chance to bridge her professional experience as a registered dietician with her competitive experience as a top-flight runner.

“The dietitian is a partner in care, not someone who is supposed to tell you what or what not to eat,” she says when asked to debunk a common misperception about the profession. “Our job is to try and help people understand the ‘whys’ behind actions and to give you more power to manage your health better.”

In her own experience, few activities proved more empowering or transformative than taking control over one’s own training and conditioning as a competitive runner. Training for a half marathon, she reasoned, was just the sort of tangible, yet challenging goal that could help transplant recipients not only achieve their goals of improved health, but also celebrate them in a meaningful, visible way.

Deckert (center) training alongside Susan Bussell (left), an RD at the UWMC outpatient kidney, pancreas, and lung transplant clinic and Team Transplant member since the group’s founding, and former Kansas Governor and then-U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius (right).

“I think for many [transplant recipients], it’s a chance to show stewardship for the gift they’re given,” Deckert says. “The whole idea of prevention and wellness starts over. Now you’re back in life. People see it as a second chance: that I’m going to make myself better than I was before.”

Participants typically start training in mid-August, meeting for group training sessions every Saturday morning at a predetermined location around Seattle as they work to gradually build up their mileage—running or walking—over a 4-month period to prepare for the 13.1 mile half marathon event. For her part, Deckert develops runners’ training schedules and organizes informational clinics on strengthening, stretching, and sports nutrition, as well as walking and hill running technique.

“It’s not meant to be [that] you have to do this forever,” she says. “For many, it’s a good way to build their confidence up so they can go do other things—whatever that is.”

One member eventually left to take up ballroom dancing. Another embarked on a months-long walk of the Camino de Santiago, the popular medieval pilgrim’s route in northern Spain that can involve walking as many as 16 miles in a day. Still others got interested in mountain climbing or used the experience to build up the momentum and endurance to continue their education.

In other words, getting up, out, and running is just the start. If team members complete the half marathon and feel ready to move on, Deckert says that means the program is working. Yet even with the turnover, three of the five original team members who received organ transplants are still involved in various ways.

“Everything goes in cycles,” Deckert says. “You can always return.”

The cyclical nature of athletics—that nothing is likely to stay constant, no matter how diligently you might train—is a fact Deckert herself knows all too well. Beneath her feat of qualifying for four consecutive Olympic Trials in the marathon flows a river of life in all its ripples and eddies.

“You have another job, you have another life, so your running ebbs and flows over the course of four years,” Deckert says. “But then you say, ‘Oh maybe I could qualify again.’”

Wearing their signature bright green colors, Team Transplant takes time out to pose after the 2016 Rock ‘n’ Roll Seattle Marathon and Half Marathon.

Her first Olympic qualifying time came at Grandma’s Marathon in Duluth, Minnesota in 1995, when she clocked a 2:44:22. To that point, since coming to the UW for graduate training as a dietician in the early 1990s, she’d been training with Tom Cotner, a longtime UW faculty member in pediatrics and legendary distance coach for Club Northwest.

She says she set out training with the goal of making Olympic Trials in mind and was quietly pleased to have reached it on her first attempt.

The road to her second Olympic Trial in 2000 was less auspicious. Shortly after competing to make the Olympics in 1996, she got injured and had to have foot surgery.

“During that four year span, I had to do a lot of coming back,” she says, adding that during that time her mother also passed away from leukemia. “There was a lot of life going on.”

On her way back from injury, Deckert was asked to coach the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Team in Training, which helps athletes train for endurance challenges around the world, while raising money to pioneer new breakthroughs in the fight against cancer.

“Part of it was trying to get back to my roots,” she says. It was the first step in the next cycle of her evolution as a runner—and toward the eventual inception of Team Transplant.

She returned in time to again qualify and race at Olympic Trials in South Carolina in 2000 and would consistently put up some of her best career marathon finishes over the course of the next decade. She stopped competing at the end 2008, but says her involvement training with and as coach of Team Transplant helped make the transition an easy one.

“I have one friend who says it’s about going from a competitive to an appreciative runner,” she says. “This is a good group for that. They help me balance where running fits into my life.”

She still runs often—alone, with the Team, and with her husband, although a knee injury this winter has proven a momentary setback. It’s not so much that Deckert is dialing back the intensity; rather, she says she’s beginning to explore the many facets of the sport to find both joy and excellence in every form.

“That’s what I’m striving for—that feeling that everything’s smooth and everything’s clicking. Sometimes, you hit a cycle where training clicks and everything falls into place,” she says. “You almost feel like, ‘Nobody can beat me today, because I’m so on it.’”

She says it doesn’t happen every day and there’s no use trying to predict it, but that it also isn’t liable to happen at all unless you put in the daily practice and take good days with the less-good days all together. That goes for elite runners and transplant patients alike—whether it’s on the day of their first race, their twenty-first, or on any given weekend run with the team around Seattle.

“If you can have that one day, it’s freedom.”

Meet some of the donors, recipients, and other members of Team Transplant and hear their stories first-hand in this series of on-the-fly videos. Learn more and get involved by visiting Team Transplant’s website or its Facebook page.