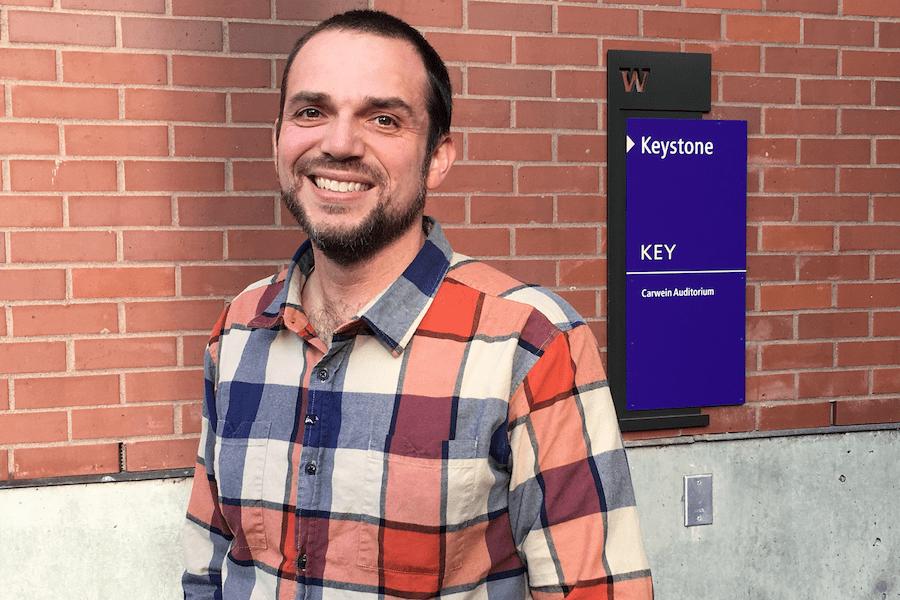

Faculty Friday: Michael Berry

If aliens were ever to land, Michael Berry thinks his music theory students would be prepared.

“I want my students to be able to figure out what makes their music tick,” Berry says, calling up connotations of the scene in 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind in which aliens and humans communicate through a series of musical tones.

Centering music, its permutations, and influences is at the heart of Berry’s work between two appointments at the UW—one as a lecturer at UW Tacoma teaching courses on rap music, music and trauma, and the history of rock and roll and another at the UW School of Music in Seattle teaching first-year music theory.

“Music schools are still very much focused on classical music training, so I’m trying to think of ways to move outside of that box,” Berry says. “Rather than teach a theory, can we teach students to theorize?”

Indeed, whether he is spending the day in Seattle or Tacoma, Berry actively tries to cast his classroom as an otherworldly, alternate space—somewhere students can access and practice forms of musical understanding, appreciation, and inquiry that they might not find elsewhere.

“When people ask me what music theory is, I always tell them it gives us a language to talk about our musical experiences,” Berry says. “For students who might have learned to play by ear, the written theory course gives them an opportunity to experience music in another way.

“Music theory is something that’s descriptive, not prescriptive.”

Teaching the toolbox

This winter, Berry is teaching the second course in the music theory sequence at the UW School of Music—something he says he enjoys because it gives him the “opportunity to work with students all year and develop good relationships.”

His primary aim with the course is to help students broaden their repertoire as theorists. That desire to broaden the definition of how music theory is applied is part of what got Berry—who, as a student, once foreswore all popular music to focus on classical studies—interested in hip-hop.

“Western classical music is very much a written tradition,” he says. “The tools we have to talk about Mozart, Haydn, and Beethoven don’t really tell us anything important about hip-hop. What would a music theory that grows from hip-hop look like then?”

It’s a question Berry explores in the course he teaches on rap music.

“There’s a very conservative view of what it means to be “musically literate” and classical and most jazz musicians are considered “musically literate” and yet pop musicians somehow are not?” he opines.

“Pop artists are every bit as musically literate, but it’s just a very different musical literacy.”

Berry says he thinks broadening the music theory curriculum beyond more classical modes of engagement will have an added effect of helping students land more paid work as musicians once they leave college. He always encourages students to accept music-playing gigs, even if they’re unsure if they’re fully qualified.

“Don’t say no. Say yes and then figure out how to do it,” he advises, citing that his desire is to help students develop a broad skill set so they can then play that up when potential employers call.

“What I do as a performer very much influences how I teach theory because most of my students are going to go out and play or go out and become music educators—or both,” he says. “If what we’re doing in the classroom doesn’t directly translate to that [real-world experience] then I’m not doing my job.”

Berry views class as a setting where students can learn to become a more complete, well-rounded artist capable of moving with versatility as a professional musician.

“Freelancing is its own skill set,” he says. “But it can be hard thing to teach.”

But Berry does his best to. Growing up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Berry learned to play classical double bass. He’d dream of one day playing in the Philadelphia Orchestra.

His first job in music after college was as a church music director.

“I don’t think there was a bass opening in the Philadelphia Orchestra for twenty years after I graduated,” he quips, noting that such factors are unavoidable when charting a career in music and that informed improvisation is often called for. Like when he arrived at Temple University and started listening to hip-hop.

“When I finally let my guard down [and started listening to popular music again], a lot of people were listening to hip-hop and, with Temple situated in North Philadelphia, I got to see a way of living that I had never encountered,” Berry says. What was then a newfound interest would later help define his role as an educator.

Berry switched his focus from performance to studying music theory, getting a master’s at Temple before moving to get his Ph.D. in music theory from the City University of New York. After a Ph.D.-level class on popular music, Berry began thinking more about his burgeoning interest in rap and hip-hop.

“It bothered me that nobody was really talking about the notes,” he recalls. “Our tools [as musical theorist] for dealing with artists like Big Daddy Kane and Rakim and Migos are kind of poor at this point, so it’s like, if we want to talk about rap as music, what kind of tools do we need to do that?”

When Berry commits, he commits. A three-time marathon runner, he once ran on a treadmill for twelve hours, covering 54 miles, in a bid to raise awareness around a Team in Training for the Leukemia Lymphoma Society fundraiser he was a part of. When it came to the idea for teaching the music of hip-hop, his approach was no less dogged.

“I wanted to be the person talking about the music theory of hip-hop,” Berry says. “I thought, ‘What if we had a class that unpacked what this stuff is talking about so students can understand what they’re listening to when they’re listening to rap in order to challenge their ideas about race and class and things like that.’”

Berry joined UW in October 2011 after teaching for seven years at Texas Tech, which is where he first experimented with an Honors College course on rap music. Berry “readily admits” he “maybe wasn’t the most equipped to handle those conversations then,” but says it was a start.

“You’ve got to start somewhere.”

The class evolved over the years; Berry along with it.

In tracking the evolution of rap and hip hop, Listening to Rap illustrates its vast cultural significance, offering a clear and accessible introduction to vital and influential music.

“It’s not just talking about the music,” he says. “It’s also about the values the music puts through and how the music is shaped.”

To talk about rap is to talk about race, Berry says. “Many of the criticisms of rap as music are criticisms that are rooted in race and so to talk about rap music is a political thing—to say this is music and here’s why it’s music.”

Berry recently finished his first book, Listening to Rap: An Introduction, an undergraduate textbook he wrote while also teaching a full load of classes.

“The title, Listening to Rap, centers the music, but the different chapters are ways into listening to music: listening to music, listening to poetry, listening to history, listening to precursors like disco, funk, and jazz and seeing how rap grew out of those things,” Berry says. “But then there’s [also] listening to race, listening to gender, listening to religion, and listening to politics because all those things come into play too.”

Beginning to think about rap as growing from the ruins of the South Bronx is an important aspect of its story, Berry says.

“It’s the music of marginalized communities, so we need to untangle those origins. We need to understand who controls what we hear on the radio,” he says, adding that his book is really an effort to come at rap from “a variety of angles” with the aim of “recognizing the forces that shape it.”

“I see it to be very much a kind of anti-racist project where we start by talking about music and poetry—objective things like end rhyme and internal rhyme, things are very much a source of pleasure in hip-hop.

“But then we need to think about how and why it is we are deriving pleasure built on music that reinforces hetero-patriarchal norms, that grew out of oppression and police brutality, to examine what is the music actually reflecting.”

For Berry, it’s about going “beyond the beats and rhymes.” To supplement classroom discussion, he bought two turntables and an old mixer, devoting time to learning the basics of turn-tabling and scratching so that he might bring the set-up in to give students them a chance to put their hands on records and scratch them.

“They learn what it takes to loop a break beat for ten seconds and they realize, “Wow, this is really work.”

Berry strives to do his best to give students—especially those in his UW Tacoma classes—hands-on opportunities in music. His music appreciation classes at UW Tacoma also provide students opportunities to write capsule album reviews, compose songs, and incentives to explore local music scenes.

“I want to be central on the music and give students opportunities to create where they might not otherwise,” Berry says.

“We don’t have a music program at UW Tacoma, so the extent to which I can offer creative outlets for students who are musically inclined, I’m happy to.”

That every student is able to bring their own experience or background in music to the table is what Berry says he likes most about teaching at the UW. “At Seattle, it’s great fun to work with the music majors because I see a lot of me in them—they just want to absorb all this knowledge about music,” Berry says. “At UW Tacoma, so I get all sorts of majors and that to me is a really great environment for talking about music.”

Berry also teaches a course on music and trauma at UW Tacoma, which largely engages students of social work.

“The benefit for me in teaching here is that I hopefully learn as much from my students here as they learn from me.”

2 Thoughts on “Faculty Friday: Michael Berry”

On February 24, 2019 at 9:36 AM, Jennifer Weiss said:

So inspiring!

On February 27, 2019 at 8:33 AM, Jen Miller said:

He is a GREAT teacher and obviously in the classroom for all the right reasons. Thank you, Dr. Berry!

Comments are closed.