Faculty Friday: Steve Herbert

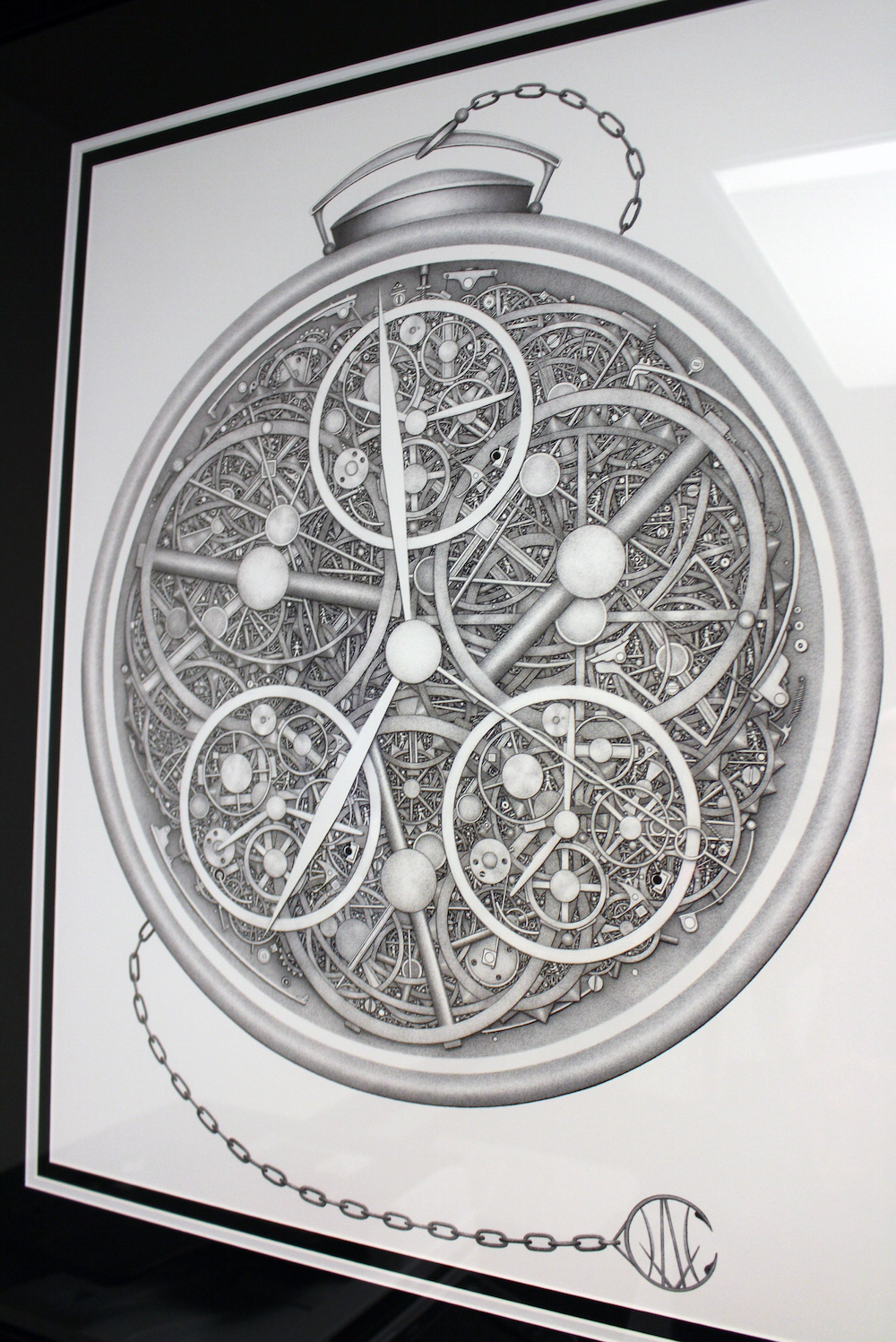

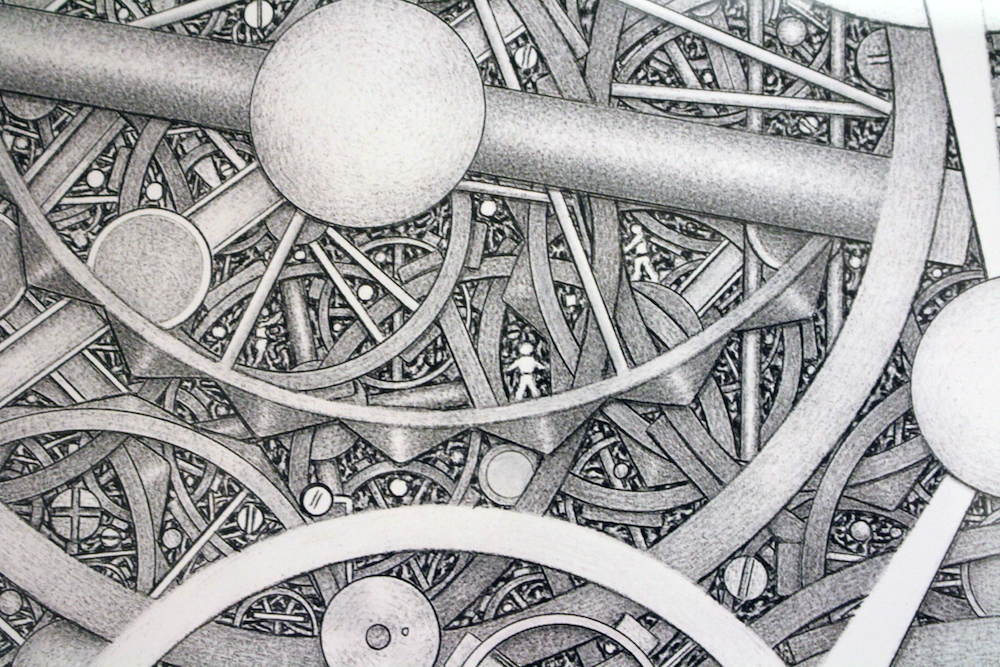

The product of more than 500 hours’ work, this pen and ink drawing created by Hoyt Crace is one of three displayed in the Department of Law, Societies, and Justice at the University of Washington. Crace discovered a talent for art while incarcerated. (Matthew Leib/The Whole U)

Step into Steve Herbert’s office in Smith Hall at the University of Washington and it’s the art that immediately catches your eye. On a back wall above his desk hang two large pen-and-ink drawings of labyrinthine detail, imbued with a spinning sense of motion through thousands of short hatch marks made by a ballpoint pen.

The effect of perpetual motion frozen in a moment recalls the work of Piranesi, an 18th-century Italian artist famous for a series of sixteen prints depicting soaring subterranean vaults crammed with cables, causeways, and catapults that foist upon the viewer a sense of awe slashed with inescapable dread.

Piranesi styled the drawings Carceri d’invenzione, or “Imaginary Prisons.” They were the product of a versatile and resourceful designer exploring the boundlessness of his creative imagination. The drawings in Herbert’s office, by contrast, are the product of an incarcerated hand, produced by a man serving a life sentence in prison without the possibility of parole.

It’s one case in which the walls really do talk, speaking directly to Herbert’s work as Mark Torrance Professor and Department Chair of Law, Societies, and Justice at the University of Washington.

This fall marked the release of Herbert’s most recent book, Too Easy To Keep: Life-Sentenced Prisoners and the Future of Mass Incarceration, which draws on extensive interviews with 21 people sentenced to life in prison without parole at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe, along with 27 prison staff in positions privy to the challenges and implications of tending to this steadily growing number of aging “lifers.”

“A lot of the politics of mass incarceration were built around the demonization of the criminal and are what made it possible,” Herbert says. “It’s that cultural narrative I believe deserves to be challenged.”

As qualitative as it is quantitative, Too Easy to Keep spotlights the harsh consequences of excessive sentences, underscoring what Herbert views as a need to reconsider punishment policy.

Herbert’s new book is out now from University of California Press

The United States criminal justice system currently houses the largest prison population in the world per capita with more than 2.3 million behind bars—more than 200,000 of whom are sentenced for life. Four times as many people are incarcerated today than in the late 1970s when interest in rehabilitative incarceration waned in favor of stricter sentencing.

“There isn’t built into our system a real strong incentive for prisoners to engage in rehabilitation because they’re not going to get a reduction in their sentence if they change,” Herbert says. “I think that’s regrettable.”

For example, Hoyt Crace, the artist who created the works in Herbert’s office, was sentenced as part of the three-strike law in Washington—the first state to adopt one.

“My goal with this book is to let these prisoners tell their stories and make clear that their desire for redemption is real,” Herbert says, acknowledging that not every prisoner is genuinely remorseful, but contending via evidence he’s collected that a significant number demonstrate an “ability to craft lives of notable purpose” and willingness to understand themselves in new ways.

“If you do challenge the idea and say incarcerated people are fundamentally redeemable and you recognize the fact that many of them do want to change, then it seems to me, we owe it to them to create the opportunities to do so,” Herbert says.

“That means going back and making the prison as rehabilitative as possible.”

On the inside

One way in which Herbert explores an alternative approach is through a partnership with University Behind Bars (UBB), which provides college preparatory and college-level instruction for inmates at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe. Several years ago, he devised a “mixed-enrollment” class, which brought together a group of Law, Societies, and Justice students to learn alongside inmates at the Monroe Reformatory.

After the first quarter, Herbert concluded it was “far more successful” than he had allowed himself to imagine.

“Part of that was because the UBB students were really good and part of it was that UW students were like, ‘Wow, these guys are nothing like what I thought a prisoner student would be,” Herbert says. “To see students reckon with stereotypes like that and then see that same group come together with their imprisoned peers was remarkable.”

It’s why Herbert sees the UBB class experience as so powerful: students have to ask themselves, where did my stereotype come from and hopefully they’ll ask that of any other stereotype they might have and confront that.

UW students work alongside inmates at the Washington State Reformatory in Monroe in 2015. (Sy Bean/The Seattle Times)

“As soon as they start interacting with these prisoners, they realize the cultural narrative about these individuals doesn’t explain the person they’re interacting with; this person is completely different from what they’ve been led to think—or fear.”

Herbert also learned that those UBB students he so admired were, by and large, serving long or life sentences.

“It shouldn’t have surprised me but it did,” he says, adding one in six prisoners in Washington is incarcerated for life. “As this number of prisoners increases—and as each of them inevitably ages—it’s going to create very significant complications.”

Herbert’s hope for the class—and for his book—is that it will continue to stimulate public conversation “about the consequences for all of us” of maintaining a growing, aging population of lifetime prisoners. It’s a conversation he’ll carry to the wider community at a Seattle Town Hall event on December 11.

“The toughest issue is the struggle that we all face in recognizing that even people who commit very horrific acts remain redeemable,” he says.

“I think it’s too easy in our culture to write people off and dismiss them somehow as inherently evil or beyond the pale,” Herbert says. “We are not recognizing there’s usually a reason a person commits a horrific act—something in their past that contributes something to their getting to that moment—and that many feel intense remorse and are eager for a way to redeem themselves.”

“Too much of our criminal justice apparatus and our political conversation about crime makes it hard for that reality to be seen,” he says. “These elements of society are not apart from it, but a part of it.”

Steve Herbert leads a class discussion at the prison in Monroe. (Sy Bean/The Seattle Times)

The 10-week UBB class is just one element of the varied Law, Societies, and Justice curriculum. Launched in 1973 as Society and Justice and restyled under its current heading in 2001, the department strives to attract “interesting students who are not afraid of complexity and who welcome questions to which there are no easy answers.”

“What we try to do is not only equip students with the conceptual apparatus to understand the world, but we also get them out into the world to witness the dynamics they’re reading about and engage in the hard work of trying to make sense of what they’re seeing,” Herbert says.

This past summer, he led a two-part course in comparative criminal justice. After an immersive two weeks studying the U.S. criminal justice system with visits to courts, police stations, and correctional facilities around the Puget Sound region, Herbert and 15 students decamped to University of Cape Town in South Africa for similar excursions.

“What’s great about getting students inside a prison or taking them to a court room is that it’s no longer just an academic exercise,” Herbert says. “It adds a completely different dimension to any classroom work they might do trying to understand mass incarceration and its consequences.”

To be able to draw upon those direct experiences, students are able to understand that nothing in criminal justice happens in a vacuum, Herbert says.

“There are cultural, political, and racial dynamics, so having to put two systems against each other, they have to ask each other, ‘why are they similar and why are they different?'”

Stepping out

Herbert was initially drawn to study geography for those distinctly interdisciplinary qualities. As an undergraduate at Macalester College, Herbert took Urban Geography as a means of exploring his new urban setting in St. Paul, Minnesota, having grown up in Lawrence, Kansas. The class’s main assignment was a field project.

“Our professor sent us out into the Twin Cities with questions and places he wanted us to go,” Herbert recalls. “As we moved through the cities, the questions became fewer as he was teaching us to develop our own capacities to ask questions about this landscape.” He loved the experience.

“It brought learning to life,” he says. “I liked it because you’re being hyper-aware of your environment, always asking questions about the world around you—that’s what geographers do.”

While at Macalaster, he studied for and received his secondary school teaching certificate, which presaged two stints teaching middle school—first in Minnesota and later in Los Angeles, where he decided to pursue a Ph.D. at UCLA.

A firsthand account of how the Los Angeles Police Department attempts to control a vast, heterogeneous territory, “Policing Space” offers a ground-level look at the relationship between the control of space and the exercise of power.

“I knew I wanted to do something on political geography—political geography tries to understand the relationship between the exercise of power and the control of territory and space,” he remembers. “That usually occurs on the national state level, but I wanted to ask those questions in a more ethnographic way.”

He was at UCLA when the acquittal of LAPD officers who had been videotaped beating Rodney King sparked civil unrest in 1992 and remembers thinking the police would be a “really good institution to explore these questions of how the exercise of power is connected to the control of territory.”

In 1993, he started doing ride-alongs with a patrol division in the LAPD, accompanying them for hours at a time equipped with little more than notebook and his capacity to observe and ask questions.

“At first, many of the officers were suspicious of me, but once they began to trust me and that I was genuinely trying to understand the role from their perspective, then they opened up,” he says.

“As a geographer, it was never my job to tell their side of the story, but it was my job to understand the role from their perspective. I was trying to figure out how space factored into all this—how they were thinking about areas and how the control of space was central to what they did.”

Over the course of eight months, Herbert rode along for everything from noise complaints to gun violence. His self-imposed rule was that, within 24 hours of any ride-along, he would sit down and type up extensive field notes while his memory was still fresh. The result was his first book, Policing Space.

“I was trying to understand the world from the police officer’s eyes, outward,” Herbert says, adding that he was all too aware their view was just one side of a many-faceted story.

That’s why his second major project—and his first at the UW—dealt with community policing and what community meant to both police and neighborhood residents in West Seattle—and what aided or impeded close working relationships between both groups.

He’d come to UW after four years at Indiana University with his wife, fellow academic and researcher Katherine Beckett. Together, they co-authored 2009’s Banished: The New Social Control in Urban America, which directly challenged the “broken windows theory” of zero tolerance policing tactics. Her office is just down the hall.

Human capacities

Now in his ninth year as director of Law, Societies, and Justice, Herbert says one of the most rewarding moments each year is the last day of the UBB class, during which the last hour is set aside for a group conversation and reflection.

“It’s remarkable how tender those conversations are after the students have only been in class together for ten weeks,” he says.

“You realize that you can cross this cultural barrier we’ve created between the good and bad or the criminal or the non-criminal pretty easily if you create meaningful opportunities for that to happen.”

For Herbert, it sends a powerful, hopeful message about a fundamental human desire to want to be the best possible person.

“Nobody wants to be judged by the worst thing they’ve ever done, and when we do something bad, we genuinely hope for an opportunity to show ourselves and the world that we’re better than that,” he says. “Just because some people’s mistakes are worse than others doesn’t obliterate that basic human need and that basic human capacity.”

That capacity is clear to Herbert every time he looks at the crisply defined lines of the drawings by Hoyt Crace that line his office walls—each the product of some 500 hours’ work.

“Here’s a guy we tossed on the trash heap—three strikes and you’re out,” Herbert says. “He wasn’t doing much in prison, but then saw some people doing art and spent hours with a Bic pen and piece of paper in his cell doing these intricate drawings.”

Some time later, the incarcerated inmate-turned-artist had his three-strike life sentence overturned by U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on the grounds that he was over-charged on his third strike felony offense.

Shortly after his release from prison, he met with Herbert and brought along some of the drawings he’d made in prison. Herbert purchased three.

“It’s an everyday reminder for me of all the untapped potential that exists out there—particularly inside of prisons—and how we gain a lot by recognizing that.”

Steve Herbert is Mark Torrance Professor and Department Chair of Law, Societies, and Justice at the University of Washington. He has served as Director of the LSJ Program since 2010. He is the author of Policing Space: Territoriality and the Los Angeles Police Department; Citizens, Cops, and Power: Recognizing the Limits of Community; and, with Katherine Beckett, Banished: The New Social Control in Urban America.

He holds a Ph.D. in Geography from University of California, Los Angeles, an M.A. in Geography from University of Minnesota, and a B.A. in Social Sciences from Macalester College.