Faculty Friday: José Alaniz

The late October rain arrived this week, but soon Seattle will be hit with a deluge of a different sort. For three days during the first week of November, comics scholars from across the world will descend on the University of Washington for The International Comic Arts Forum, the largest gathering of its kind in North America.

Somewhere close to the center of it all, you’ll find Jose Alaniz.

An associate professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Washington, Alaniz has served as chair of ICAF’s executive committee since 2011. He describes the Forum as a hybrid: one part academic conference and one part gathering of artists.

“It brings together a really remarkable group of scholars and people,” Alaniz says. “Our attendees get direct access to world-class comics scholarship and artists, while those artists get to respond to questions posed by leading specialists in the history and sociocultural significance of comic art they will not hear at a regular festival or comic con.”

A traditional comic con it’s decidedly not. Over the course of three days, attendees will present 45 stringently reviewed academic papers, while also mixing it up with some of the most talented artists and storytellers at work in the field today.

Such as Japanese manga artist Moto Hagio, “the founding mother” of modern shōjo manga who Alaniz calls “a living legend.” Or Jesús Cossio, a renowned comics journalist from Peru, who will present a solo talk as well as take part in a comics journalism roundtable alongside Joe Sacco, known for his comics journalism on Israeli–Palestinian relations and the Bosnian and Iraq wars, and Sarah Glidden, a comics journalist who has reported throughout the Middle East.

“Either of those events would be more than worth the price of admission if we charged it,” says Alaniz, who adds that, in the spirit of accessibility, the events are kept open and free to the public so long as there are seats. “Anyone with an interest in comics—irrespective of genre, national tradition, era—is welcome to attend.”

With a rise in comic-inspired culture reflected in the preponderance of superheroes flashing across screens big and small, Alaniz says he sees the field as being more vital than ever, calling comics “a very global institution.”

His own body of work reflects the medium’s world-spanning scope. In 2010, he published his first book, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia, followed in 2014 by Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond (since 2014, he has also served as director of the UW Disability Studies program). What his scholarship doesn’t speak to, however, is singular plan. Rather, Alaniz’s career is the sum of a dedicated fusion of divergent abilities and interests.

Moscow Calling

Alaniz grew up in Edinburg, Texas, the son of an immigrant Mexican mother and a Mexican-American father—both farm workers. He recalls reading Marvel comics from a young age—quickly developing into “a dedicated fan of the Hulk.”

“They were very important just in terms of getting a moral code,” he says of comics, adding that trips across the border—then much more open than it is today—and spending a lot of time with Spanish-speaking grandparents who lived nearby also proved formative.

On graduating high school, Alaniz signed up for the Army Reserve on a whim and, after moving to attend UT-Austin, was assigned to a unit and given the choice of learning German or Russian.

“I knew nothing about Russia,” he says. “The one thing I knew about Russia back then was probably Chernobyl—plus the movie Moscow on the Hudson and the Russian-based patois from A Clockwork Orange.”

The Army sent him to learn Russian at the Defense Language Institute in Monterrey, California. Returning to college, he double majored in Russian and RTF (Radio, Television, and Film) and, upon graduating, moved to Russia in 1993, taking a job as a journalist working the arts beat for the English-language Moscow Tribune.

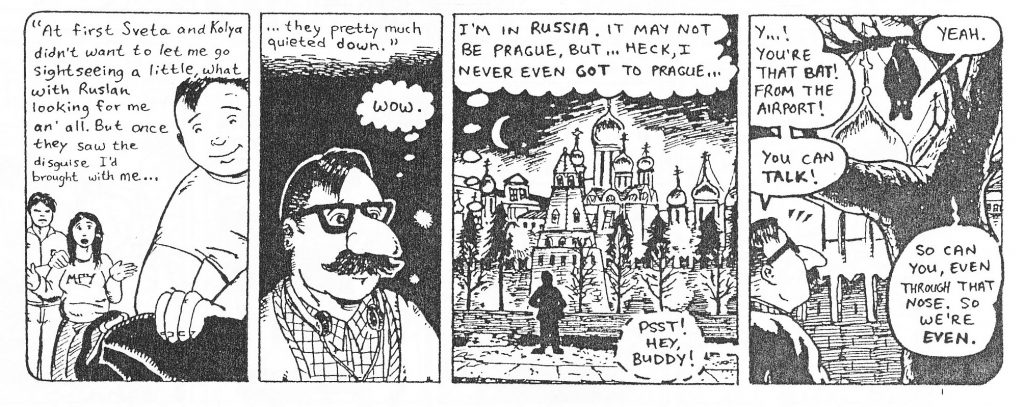

In addition to reviewing films, he indulged his lifelong love of comics by drawing and publishing Moscow Calling, a daily strip that ran for nine months in 1993 and 1994—likely the first English-language strip to ever appear Russia.

Through contacts at the paper, he met Georgy “Zhora” Litichevsky, one of longest active and most influential figures in Russian comics—a field whose pantheon of legends pales in comparison to those of the country’s other literary traditions.

Alaniz’s comic strip Moscow Calling ran in the Moscow Tribune from 1993 to 1994.

“There were very few Russian comics available and I started wondering, ‘Well, why not?’ Everything else American was being embraced by the Russians at the time—blue jeans, skateboarding, video games, the early Internet, movies—everything except comics—and I thought, ‘Why not comics?'”

After a year in Moscow, he carried the question to Berkeley with the plan of pursuing a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature.

“It took me two tries, but I eventually got in,” he says. “My big lesson to all my grad students is, just because you get rejected the first time, don’t think you can’t try again.”

At Berkeley, he completed a dissertation on death and dying in Russian culture, and, on receiving his Ph.D., was hired by the UW Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures.

“I can’t think of too many places that would have let me thrive and prosper the way I have here,” he says, adding that, while he feels lucky to have gotten a job, the UW was one of the few places he seriously considered working after graduate school. “Since coming here I’ve been surrounded by a great cadre of colleagues, people who have not only influenced me in my thinking, but who have also been very supportive about my own work—it was really here that I wrote the bulk of my book on Russian comics.”

Alaniz says his ability to do so sprung more from a confluence of these academic currents than a sense of superior scholarly ability.

“I’m not the world’s greatest Slavist; I’m not the world’s greatest comics historian; but I had enough of those skills where I could write a book about it,” he says, adding that it’s his great desire to see a second generation of scholarship on the subject. “I would be happy for my research to become obsolete, superseded, built on.”

Until that day comes, there’s more work to be done. Alaniz regularly teaches courses on comics; this quarter he is teaching C LIT 250: Animals in Graphic Narrative, a Freshman Collegium Seminar on Wonder Woman, and a graduate microseminar on the work of comics scholar and ICAF keynote speaker Ramzi Fawaz. Winter quarter, he plans to offer a course on Disability in Graphic Narrative. Besides teaching, he’s also in the process of writing a follow-up book, tentatively titled Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia that will focus on the last 25-30 years of the genre’s development in Russia.

“It really is a whole different landscape,” he says of how much the art form has evolved in the country, even in as short a span as the last decade. “There’s still not an industry in Russia per se, but now you go to bookshops in Russia and they’ve got whole sections of comics—a lot of them are foreign; a lot of them are translations—but some of them are home-grown; this wasn’t true five or ten years ago.”

In addition to crediting collaborations with Society of Scholars, the Simpson Center for the Humanities, and comics organizations like ICAF for helping propel his work forward, Alaniz says Seattle and the Pacific Northwest are incredibly conducive environments for comics scholarship.

“There’s a real synergy here of academics that are interested in comics as well as comics producers—comics artists—as well as publishers such as Fantagraphics,” he says. “It’s a wonderful community—Dune, the sadly defunct Cafe Racer, the Short Run Comix and Arts Festival, Fantagraphics—they just created this environment.”

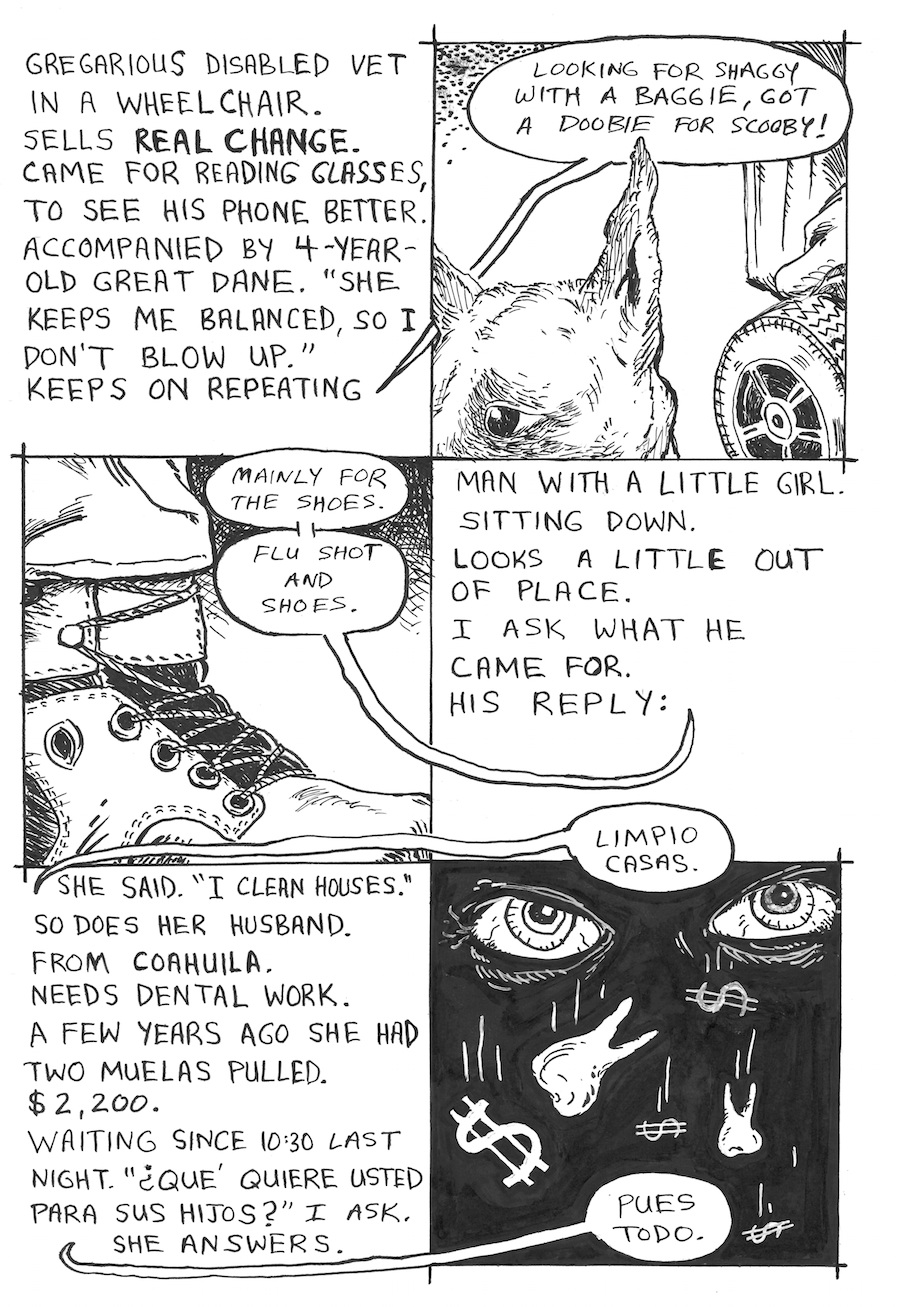

A nonfiction comic Alaniz created at the Seattle/King County Clinic at Key Arena.

It’s an environment that’s drawing Alaniz back to his roots as a creator of comics in his time away from the classroom.

“A lot of people who know me as a comics scholar and professor don’t realize that I make comics as well as write about them,” he says. “That’s always been a central part of me: I’ve always been someone who draws and cartoons and would love if it people would start thinking of me as someone who also makes comics.”

He’s taken his craft into the community as well, joining a cadre of comics journalists to document the annual free Seattle/King County Clinic at Key Arena to tell the stories of its underserved patients—literally illustrating the needs of a representative fraction of the 11,900 people who’ve received care there between 2014 and 2016.

“It’s about demonstrating that this is a great service, but also that we wouldn’t need it if we had adequate healthcare for people that they could afford,” Alaniz says.

At this year’s clinic, which runs from October 26-29, Alaniz says he plans to adopt a migrant-specific focus, utilizing his knowledge of both Russian and Spanish to convey in comics form the experiences of non-English speakers.

“They’re very much below the radar—especially undocumented people,” he says.

It might not be a superpower, but in so far as his cartooning is a skill born of unique circumstance, it’s a power Alaniz is bent on using for good.

José Alaniz holds a B.A. in Russian Language and Literature and a B.S. in Radio/Television/Film Production from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of California at Berkeley. The International Comic Arts Forum will run from November 2 through November 4.

On November 6, don’t miss a solo event on the UW campus with ICAF guest Emil Ferris, author of the celebrated graphic novel My Favorite Thing is Monsters, published by Fantagraphics. Concurrently with ICAF, both the Suzzallo and Odegaard libraries will hold comics-related exhibits exploring the Seattle comics scene; the history of ICAF; and other related subjects.