Faculty Friday: Julie Kientz

For the second day in a row, Julie Kientz blacked out at the sight of blood. When she came to, lifted from the floor of the veterinarian’s office where she was participating in a job-shadowing program, the eleventh grader from Ohio decided it might be time for a change of career plans.

“I love computers,” she recalls thinking in that moment. “They have nothing to do with blood. Why don’t I try that?”

Today, Kientz (pronounced, “Keentz”) serves as an associate professor in the department of Human Centered Design and Engineering at the University of Washington. She might not be practicing veterinary medicine as originally planned, but she is busy tackling human health challenges of a much greater scale. As director the Computing for Healthy Living and Learning Lab, she has an academic vantage point that affords her a wealth of collaborative choices.

“The blessing and curse of a school like the UW is that there’s great research going on everywhere and I just want to be involved in all of it,” says Kientz, who in nine years at the UW has leveraged her computing acumen to develop applications that target health problems at a wide intersection of people and technology: childhood learning and interaction, sleep technology, assistive technology for people with disabilities, and smoking cessation, to name just a few. In 2013, she was named one of the MIT Technology Review’s 35 innovators under the age of 35.

“I’ve been motivated by how we can use computing to improve peoples’ lives,” she says. “The thread that runs across all my research is trying to reduce the burden of technology through design.”

In other words, technology is only as useful as it is easy, convenient, and intuitive for people to use. Kientz explains that, in her models, ”user burden” divides into six components: mental and emotional burdens, physical burdens, privacy burdens, financial burdens, difficulty of use burdens, and time and social burdens.

“[Computer scientists] often tend to have this, ‘if we build it, they will come’ mentality,” she says. “But the world is filled with graveyards of technologies that no one ever uses, because they haven’t really thought it through.”

To illustrate the concept of user burden, Kientz cites Baby Steps, a program she helped build to assist parents and doctors in recording developmental milestones. At present, most developmental screenings take the form of questionnaires distributed in a variety of settings, such as a doctor’s office, health fair, or preschool, but Kientz says overall coverage is “spotty,” with some children getting screened multiple times, whereas others slip through the cracks.

“If you can get kids early intervention services, the impact of developmental delays later on in life can be significantly lessened,” she says. However, parents are often trepidatious at the prospect of “looking for things that are wrong with their child.”

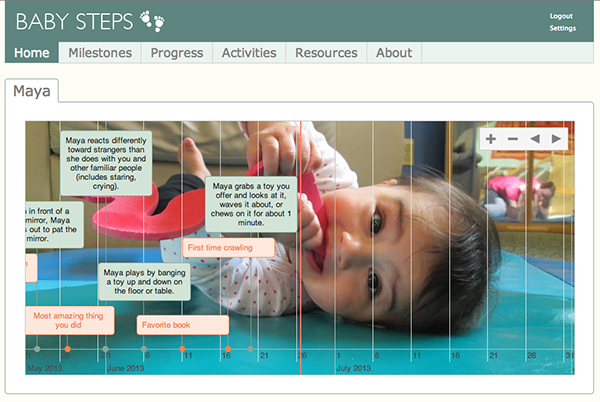

An example of how Baby Steps’ interface charts development milestones.

She describes Baby Steps as “a digital baby book” that strives to “flip the framing around” the issue to transform developmental tracking into one of celebrating children’s achievements, instead of simply searching out problems.

The program, which recently finished a 15-month, 150-family study, encourages parents to log their child’s development over time using a portal that functions across multiple technological and social platforms. Parents can upload progress updates in the form of text or photos and, in return, receive feedback on their child’s development. If a child is a bit behind on achieving developmental milestones, Baby Steps suggests actionable activities for parents to engage children in ways that encourage development or, if called for, connects parents to services for support.

“We’re basically trying to build a system that will help do developmental screening for every kid in the state with the ultimate outcome of increasing both the number and diversity of kids who get screened, improving parents’ understanding of normal development, and reducing anxiety around screening overall,” she says.

Kientz calls it “an interesting design challenge,” because in order to build a system that works for everybody, the technology must function on multiple platforms to provide access points that cut across Washington’s socioeconomic spectrum.

“When you think about things from a population level, you can’t expect people from every population to come to where you are,” she says.

Baby Steps accounts for technology’s “financial burden” by providing lower-income parents who might not have reliable access to broadband a responsive text message-based functionality. In turn, it seeks to address the “emotional burden” of telling parents that their child might be behind the curve by ensuring the process of logging development is as celebratory as possible, including reflective prompts you might find in a classic baby book so families can document “all the fun stuff about their kids,” interspersed with questions that would be relevant to a doctor.

“We’re hoping to make something fun for families to do that helps them connect with their child and learn about what they’re doing, get ideas for what to do with them, and build competency and confidence as a parent,” Kientz says. “That, and connecting people to the right services.”

While only 10% of the population may be flagged as needing a followup or having a developmental delay, it’s Kientz’s hope that injecting “fun” into the program’s functionality will ensure the widest user base—empowering parents without overwhelming them or giving them the sense that technology is being forced upon them. At present, Kientz has been building a coalition of partners within Washington—ideally publicly and at the state level—to further implement and grow the program.

“We have a long-term view of what we’re doing and we want to make sure we’re doing it right in building a tool families will actually use,” she says. But even though she’s committed to a meticulously planned rollout, she says people from a number of other states have already reached out to express interest in the system.

Far from using computers to optimize human health, Kientz sees computers as a link that’s only necessary so far as their ability to connect people to resources and, ultimately, other people. That, she says, is where progress truly lies.

“I’m usually very much about talking to people, learning from people, hearing about what kinds of things are problematic for them and brainstorming a solution about how we can solve that and being very open-minded about what that solution might be,” she says.

It’s an extension of research she’s even managed to carry into her own personal life. In between lab work and teaching classes in user experience design, user-centered design, design methods, and assistive technology through adjunct appointments in The Information School and Computer Science & Engineering, Kientz will occasionally collaborate with her husband, Shwetak Patel, a professor in the Department of Computer Science & Engineering.

They first met working in the same graduate lab as Ph.D. students at Georgia Tech. Several years into the program and shortly before they started dating, Patel hacked into a computerized gumball machine Kientz kept at her desk programmed to dispense candy every time someone visited her personal website, flooding her desk with gumballs in the process.

Both were hired as professors at the UW in 2008 and were married in Seattle two years later. Together, they have two children, ages two and four.

“That’s lucky,” she says. “We’re very grateful for sure.”

Julie Kientz holds a B.S. in Computer Science & Engineering from University of Toledo and a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the Georgia Institute of Technology.