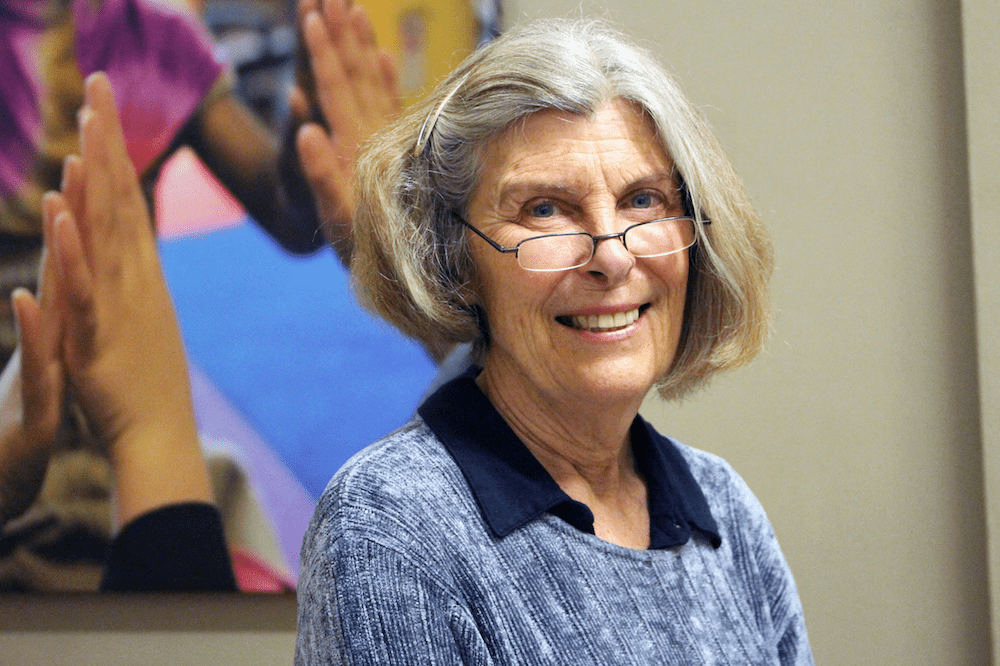

Faculty Friday: Karin Frey

Karin Frey says she gets all her best ideas from teenagers. A research associate professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Washington’s College of Education and primary investigator at its Sociomoral Action and Identity Lab (SAIL), Frey says talking to teens is one of the aspects of her work she likes best.

“When I talk to teenagers, I find out things about myself,” she says. “Part of the fun of interviewing teenagers is that, because they are often uncertain, they spend a lot of time thinking about their behavior and wondering if they did the right thing. Adults often don’t inspect our behavior to the same degree.”

Over the past ten years, Frey has talked to hundreds of teens—most often about topics such as bullying, revenge, and belonging—really, any interaction that might constitute an expression of social power or involve strategies of conflict or cooperation in adolescents.

“We tend to trivialize these problems because kids can sometimes get engrossed in things that do seem pretty trivial, but if you think about teenagers being poised between childhood—when other people protected and care for them—and adulthood, when they’re going to be protecting and caring for others, then these situations that are so important to them become really understandable. We should recognize that they are important ways of rehearsing for those adult skills.”

Frey says the transition from childhood to being a young adult is a critical moment when young people learn to protect and comfort those who are vulnerable, making it a ripe time to investigate teens’ judgment, emotions, and reasoning.

“Helping friends is key to teens’ views of themselves as competent, good people,” Frey says. “They don’t necessarily know the best ways to help, so they can be very self-critical.”

“Helping friends is key to teens’ views of themselves as competent, good people,” Frey says. “They don’t necessarily know the best ways to help, so they can be very self-critical.”

When kids do things that amplify negative emotions in peers and that risk escalation, teens tend to feel guilty and ashamed, Frey says, adding that they can also feel intensely proud when they help peers resolve problems peacefully.

“We often find that when kids feel they’ve helped someone, they feel more competent themselves,” she says. “I suspect many teachers don’t recognize to what effort kids go to make sure their friends are both protected and staying out of trouble.”

Frey usually conducts studies over the course of several months during the summer. In her interviews with students, she asks them about instances in which they might have started a rumor, engaged in verbal confrontation, or become physically aggressive in order to avenge a friend.

“That kind of third-party revenge is really interesting compared to personal revenge because it has both pro-social and anti-social elements,” she says. “The pro-social element is that you’re trying to provide justice or protect someone—and kids feel really proud about that. But at the same time, they’re harming someone. When you talk to teenagers they provide a very sophisticated moral self-evaluation about their behavior.”

This December, Frey and two colleagues received news that a paper they prepared on their most recent study was accepted for publication in the Journal of Adolescent Research. It chronicles a study examining how young people evaluate themselves and their actions when a friend or peer has been victimized.

“It is common for teens to amplify the friend’s anger or keep them out of trouble by calming the friend down,” Frey says. “They also avenge their friend’s victimization or help them reach some resolution.”

The impulse to take revenge on behalf of someone is fascinating to study, Frey says, because it has both cultural and physiological roots both in deeply-embedded societal notions of honor culture and how the impulse to protect relates to oxytocin the care-giving hormone. Frey has observed that, when talking about their actions, young people will often talk about their self-identity—“the person they feel they are or the person they want to be.”

“They end up telling us how they became aggressive at some point and then reflect on whether that was their true self,” Frey says. “They may talk about an action they may not be proud of—something they did in the heat of the moment—and then they may finish by saying ‘that’s not me.’”

Frey says the feeling of authenticity that you’ve acted in concert with the person you want to be is a powerful and important feeling for young people and that it speaks to widespread feeling at that age that “suggests they’re often in a position of not feeling quite right.”

“One of the things I love about teenagers is they tend to be very idealistic,” Frey says. “Justice is something they think about a lot.” Development of that sense justice often starts on the sports field or in the schoolyard, but it increasingly finds vent in the wider world as well—as it has recently on issues such as gun control and a changing climate.

“When you think about climate change, we’re treating young people unjustly by not doing anything about this,” Frey says. “It’s unconscionable that those who have gotten wealthy with our carbon-intensive economy have strategized to hoodwink so many people. Teens’ idealism, thirst for justice, and understandable concern about the future makes this a really important moment because they have a moral position that is much stronger than people of my generation, because we’re not going to be around to see the worst of it. The fact that teenagers are starting to demand a hearing for those issues is really important.”

Frey says she sees a similar sense of justice reflected at the College of Education, which she describes as “having an extremely strong social justice orientation,” supporting work that “tries to provide a voice to those kids we don’t hear from.”

Theirs are voices Frey has only become more interested in elevating the longer she’s been a researcher. “Over my career, which has been a long one, I’ve tested 14-month-old babies and I’ve surveyed 70-year-old runners about their motivation, but I always came back to teenagers.”

Growing up in Southern California, Frey was always interested in development—something she ascribes to observing her brother, who was eight years her junior and had a hearing deficit that was undiagnosed until the second grade.

“I was in a position to see how that influenced his development—having an awkward, unsatisfying, sometimes confrontational relationship with teachers early on that was partly a function of just not hearing really well.”

However, she says that idea of formally studying development through educational psychology only occurred to her once she reached college. “When I was younger, I remember thinking, ‘How do you get to be a college professor, because isn’t college the highest there is?’ No one in my family had gone to college. Becoming a professor was very mysterious.”

In completing a PhD in Developmental Psychology at the UW and a two-year post-doc NIH fellowship in Social Psychology at Princeton University, Frey discovered she loved research.

In completing a PhD in Developmental Psychology at the UW and a two-year post-doc NIH fellowship in Social Psychology at Princeton University, Frey discovered she loved research.

“I always come back to asking questions and writing about them,” she says. “I just found I always had a zillion questions.”

One of the most common questions she hears parents ask is if kids should retaliate in instances when they’ve been bullied.

“Some kids are able to escape being bullied by becoming bullies, but it’s a high-risk strategy, because if you fail, it gets even worse,” she says, adding that a lot of the literature around bullying tends to assign people to roles. “Our research shows kids take different roles at different times and that most young people experiment with bullying at one time or another.”

She says a big jump occurs before fourth grade when kids realize they’re “the older kids in their school” and begin experiencing power for the first time.

“It makes sense that kids would experiment with power and its going to start off in very concrete ways,” Frey says. “Bullying is a concrete way of exerting power. The problem is, if kids are reinforced in that behavior, it becomes habitual and they can get stuck with a limited toolkit for dealing with conflict.”

Adults should focus on ways they can reduce the rewards kids get from bullying, which Frey says often increases as the school year goes on.

One of the most effective strategies she has found for decreasing bullying is training children to avoid bystander behavior that rewards bullying, and to provide support that enables victims to act strategically instead of impulsively.

“It’s one thing to support emotional regulation, but it’s a lot easier to regulate your emotions if you feel justice is being served and that people will take action on your behalf.”

As Frey’s career testifies, the first step is to ask questions then listen.

The Whole U invites you to join Dr. Karin Frey on Tuesday, February 18 at the HUB for a special lecture about adolescents and school bullying. Learn more and register to attend here.