Faculty Friday: Devin Naar

Devin Naar is a natural storyteller. In order to relate the rich yet fragmented history of the tens of thousands of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 and their descendants, you have to be.

It’s a story spanning centuries and continents—from the ancient port city of Salonica in what is now Greece to Seattle and the shores of the Salish Sea—and one that Naar largely pieced together himself. But to tell a story accurately and well, you first have to know what happened.

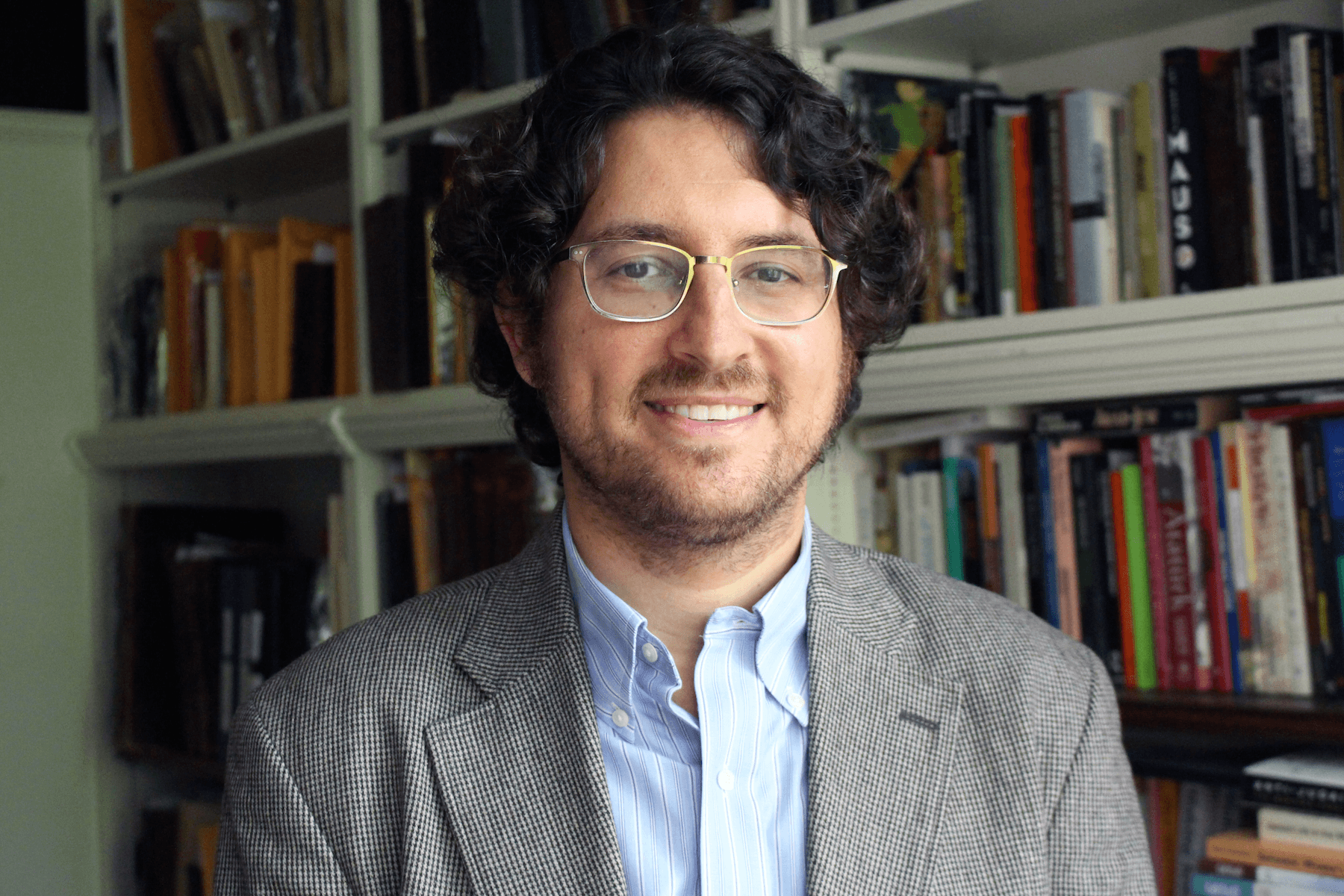

Today, Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies at University of Washington with a joint appointment in the Jackson School of International Studies’ Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and in the department of History, where he is also director of graduate studies. But when he first began investigating his family’s Salonica roots, he was a teenager from New Jersey with lots of questions and little in the way of answers.

Today, Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies at University of Washington with a joint appointment in the Jackson School of International Studies’ Stroum Center for Jewish Studies and in the department of History, where he is also director of graduate studies. But when he first began investigating his family’s Salonica roots, he was a teenager from New Jersey with lots of questions and little in the way of answers.

“I had a strong sense of intimacy for the world from which my family came, but at the same time, I had a very strong sense of estrangement,” Naar says, relating how his great grandfather, Benjamin, a rabbi in Salonica’s community of some 50,000 Sephardic Jews, emigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1924.

In passing from the control of the Ottoman Empire to the expanding Greek nation state during the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, Salonica underwent a demographic shift that placed the city’s Jews in a minority for the first time in nearly five centuries and resulted in the expulsion of the city’s Muslims.

The Ottoman Empire’s administrators had long afforded Jews more protections and autonomy than they received elsewhere in Europe. Made to feel like immigrants in their own city, many of Salonica’s Jews—like Naar’s great grandfather—chose to move away.

Naar says that lingering sense of distance he felt as a youth could be traced to the fact that so much about his family history during that time seemed shrouded by a veil of unknowns. At times Salonica felt tantalizingly familiar—like when he’d eat the city’s staple foods at home growing up—but at other times, unfathomably complex.

For example: his great grandfather was a rabbi, but wore an Ottoman fez; the family lived in a part of the Ottoman Empire that had become part of Greece, but spoke neither Turkish nor Greek at home; his grandfather attended a French school as a child, yet Naar called his grandfather nono, which is Italian. He wondered: how did all of these pieces fit together?

Those in Naar’s family who had remained in Salonica–his grandfather’s brother, Salomon, his wife Ester, and their two children—would later perish in the Holocaust during the Second World War.

When Naar’s great uncle submitted a testimony in memorial to Salomon and his family to Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, Naar recalls being struck by the fact that the date of Salomon’s death, his place of death, and his country of origin were all marked as “Unknown.”

“How could these seemingly crucial components that one would want to submit in a page of testimony not be known?” Naar remembers thinking at the time. So he began asking relatives if they possessed any historical documents that might be able to shed light on any members of the family that had stayed in Salonica.

His great uncle furnished a cache of letters, books and photographs, but expressed resignation that there was no one left who could read them as they were written in Ladino—the Judeo-Spanish language developed by Sephardic Jews who settled in the Ottoman Empire after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. Influenced over the centuries by Turkish, Arabic, Greek, Italian, and French, Ladino was historically written in Hebrew letters.

Growing up, Naar heard Ladino spoken among his grandparents’ generation, but no one ever spoke to him in the language. Even with a grounding in “high school Spanish and Bar Mitzvah Hebrew,” it was not a language he could easily understand.

“Until the early 20th century, Ladino was an all-purpose language for Sephardic Jews in the Ottoman Empire—used at home and on the street, in the synagogue and at the market; it was the language of journalism and politics, storytelling and folksongs, literature and theater,” Naar says.

“But for those who came to the United States, due to the pressures to assimilate into America that many immigrant communities feel, Ladino wasn’t really passed down to the next generations.”

Determined to decode the family missives, Naar was able to locate a library book of old Hebrew scripts that contained a chart outlining the basics of Sephardic Hebrew cursive known as soletreo.

“I sat down and started to decode these letters character by character,” Naar says. “They ended up revealing the fate of my great uncle and his wife and two children Benny and Shelly who were ultimately deported to their deaths in Auschwitz.”

“Once I discovered that information, I knew that I had to learn more.”

Entering a “lost world”

What started as an investigation into family history conducted in free time on the weekend soon spiraled into a career.

Syllable by syllable, each subsequent letter Naar translated revealed more about the fate of Salomon and his family as the Second World War overtook Europe. Naar learned from the letters that the family had been one of the last in the city as its entire Jewish population was systematically deported to the concentration camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“They observed with their own eyes the virtual elimination of the entire Jewish community of Salonica,” Naar relates. “Within a few short months, 20% of the entire city disappeared virtually without a trace.”

Of the 50,000 Jews in Salonica before the war, only 1,200 survived. The city’s 60-some synagogues were razed by the Nazis while a Jewish cemetery the size of 80 football fields with more than 350,000 graves was destroyed by the local Greek authorities and a university built on top.

The first news Naar’s family received from Salonica came from a work colleague of Salomon’s who had survived the war and wrote them in late 1945 to tell of Salomon and his family’s tragic fate.

It would be decades before Naar’s determined digging revealed a more complete version—four more stories among the one million Holocaust victims at Auschwitz and of the six million Jews murdered by Nazis during the war.

“When you realize that among those nameless victims, there was my great uncle, my great aunt, my cousins—their story, my family’s story, became my story,” Naar says. Having set out to unravel the mystery of his family’s legacy in the city once known as “a Jerusalem of the Balkans,” Naar felt he had to keep learning more.

“Knowing about the processes of destruction was not enough,” he says. “What about the life and world that once was—a world of the Jews of Greece from which there are very few memories left today?”

Naar felt a sense of obligation to speak for “those voices that have been obliterated or otherwise forgotten.”

“The seeds for my career as an historian were planted.”

From Salonica to Seattle

Published in 2016 by the Stanford University Press, “Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece” received the National Jewish Book Award and the prize for the best book from the Association of Modern Greek Studies.

Those seeds blossomed in 2016 in the form of Naar’s first book, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece, the result of an international effort to track down records and archives that had been removed from the city during the war and subsequently scattered throughout the world with caches as far afield as New York, Jerusalem, and Moscow.

In 2005, Naar located a vast store of documents in Salonica that had lain forgotten in the back room of a building since the 1940s.

“That was like an historian’s dream come true,” he says. “A huge cache of dusty documents that nobody had looked at before.”

The vast trove provided Naar with a whole new set of perspectives from the past—those of community leaders, journalists, intellectuals, and everyday people from all walks of life and political outlooks. He now had his window onto a heretofore-lost world of merchants and rabbis, port workers and tobacco laborers, gangsters and lemonade vendors.

The documents also revealed that, even before being almost entirely wiped out by the Nazis in WWII, Salonica’s Sephardic Jews were concerned about their identity and experiences being assailed and marginalized in a century increasingly defined by borders, nation states, and military might.

“The lack of recognition and absence of comprehension was part of a broader historical, cultural, and political set of structures that have relegated Jews from Salonica and Sephardic Jews more generally to the margins—if not excluded them completely—from collective Jewish consciousness, the Greek national imagination, and from other dominant narratives,” Naar says.

One of his goals for the book was “to change what we think about the city of Salonica; to compel us to reconsider our assumptions about Jewish history and Sephardic Jews in particular.” Through that process, he also hoped to probe questions “about the interconnectivity of Europe and the Middle East and the place of minorities in our modern world.”

Those questions have driven much of Naar’s research over the past three years, including an examination of U.S. immigration policy through the lens of the Sephardic Jewish experience. The new Johnson-Reed immigration restriction law enacted in 1924 made it extremely difficult for Jews to enter the country otherwise. As a result, one of Naar’s great uncles entered the U.S. from Mexico in 1925 under an assumed name, claiming to be Mexican.

“My great-uncle’s story is representative of the illegal nature of much of Jewish immigration to the United States,” Naar wrote in an essay on Sephardic immigration published in Jewish in Seattle. “Jews, like many others, both entered the country via illicit means and fought against the very restrictionist measures that were keeping them out.”

Naar’s recent work also explores how Sephardic Jews were able to rely on “flexible cultural identities” to pass (yet not be accepted) within a white supremacist society.

Another new essay, published in Jewish Currents. explores notions of Jewishness and white supremacy as expressed toward Sephardic Jews in the U.S., challenging readers to “confront the inconvenient truth of deep-seated intra-Jewish prejudice.”

Recuperating “those cultural, linguistic, and religious legacies that have been marginalized,” Naar argues can be “a step toward a broader goal: the decolonization of American Jewish life.”

These further avenues of inquiry have served as a powerful undercurrents for Naar in the development of the Sephardic Studies Program into a world-renowned center for the study of Sephardic history and culture as well as the Ladino language. That Seattle is home to one of the most vibrant Sephardic communities in the United States has also been a great factor for its success.

“Some of the early Jewish pioneers from the Ottoman Empire were alerted by Greek friends to economic opportunities that were available if they took the train to the ends of the Earth—meaning all the way west—and they wound up coming to Seattle,” Naar says, sharing that some of the first fish merchants at Pike Place were, in fact, Sephardic Jews.

“The University of Washington is unique because this is one of the few universities in the country where, because of the composition of the local community, we have students who are Sephardic or of Sephardic background,” Naar says, acknowledging the major role community support has played—including from the Isaac Alhadeff Foundation—in making the Sephardic Studies Program possible.

Its cornerstone initiative, the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection (SSDC), reflects five years’ work to assemble the world’s largest repository of digitized Ladino texts—allowing anyone to trace and explore the experiences of Sephardic Jews across time and place.

On June 2nd, 2019, the Stroum Center for Jewish Studies’ Sephardic Studies Program hosted the public program, “Seattle Sephardic Legacies.” Sponsored by a National Endowment for the Humanities Common Heritage Grant, the event not only was a chance to highlight the many facets of SSDC, but also an open scanning opportunity for attendees to share and digitize family artifacts.

Every item included in the SSDC challenges long-standing assumptions and dismissive assertions about Ladino literature. For example, Ashley Bobman, one of Naar’s former undergraduate students, received the 2014 UW President’s Medal for a digital exhibition she created on the life and world of her great grandfather, Albert D. Levy, one of the most important Ladino journalists and poets of the 20th century.

From novels and newspapers to prayerbooks and private correspondence, SSDC forms a treasure-trove of the kinds of research materials Naar once could scarce have imagined accessing with ease.

“It’s a real pleasure and honor for me to have that chance now at the University of Washington—to make that access available and to permit undergraduate students to connect to that part of their heritage,” Naar says, adding that most students interested in Sephardic history do not have a personal connection to the culture. “They approach the subject with a genuine interest and curiosity about a swathe of human history that challenges assumptions about the relationships between Europe and the Middle East, Jewish-Muslim relations, and Jewish identity in general.”

In his capacity as chair of Sephardic Studies, Naar aims to keep fostering those connections that lead to new discoveries and insights, relating that “here in Seattle, there are stories to still be told, documents to be uncovered, and experiences still waiting to be reclaimed.”

Events like Sephardic Studies’ signature annual International Ladino Day, held this year on December 5, provide further chances to connect, collaborate, and celebrate Ladino life and literature that, until recently, risked being lost forever.

Exploring Sephardic Life Cycle Customs, Ladino Day will take place on Thursday, December 5 from 7:00 pm – 9:00 pm. Learn more about how to get involved here.

“We’re in an era now of globalization in which many languages are in danger of becoming extinct,” Naar says.

“Ladino is a language that brings with it connections between Jews, Christians, Muslims; we see connections between Spain and Turkey and North Africa and Seattle and I think it really provides us with an opportunity to focus on points of intersection.”

There’s a question Naar likes to pose students at the beginning of some of his history classes: “What impact did the fall of the Ottoman Empire have on Seattle?”

Without the context of the ensuing quarter’s coursework, the query is intended to be head-scratcher that piques students’ sense of curiosity.

But at the start of some future quarter, in another part of the world, a professor might well pose a similar riddle: “What role did Seattle have in preserving and promulgating the story of Sephardic Jews?”

With Devin Naar’s help to tell it: a significant one.

The Sephardic Studies Program is actively collecting photographs for the Sephardic Studies Digital Collection. They are specifically interested in photos that document: birth; berit mila (circumcision); pidyon ha-ben (ceremony for the first born son); zeved ha-bat (baby naming for a girl); bar/bat mitsva (Jewish coming of age); weddings; funerals/mourning. Please share photos on this form.

They are also interested in hearing memories, reflections, and impressions of Sephardic life cycle events that you experienced. Did your wedding have a Sephardic twist? Does your family have unique traditions related to celebrating birth, death, or anything in between? Share those memories here.

One Thought on “Faculty Friday: Devin Naar”

On October 4, 2019 at 8:53 AM, Cheryl Forsberg said:

Very interesting article. It is wonderful that so much history that ight be unknown is brought to light.

Comments are closed.