Faculty Friday: Thomas Hawn

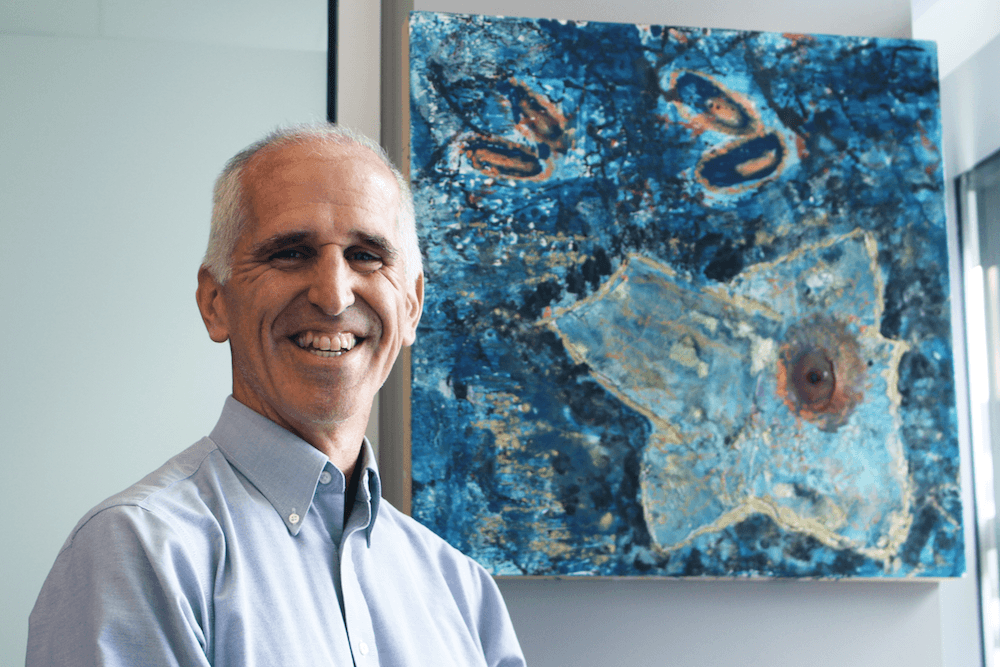

A riot of blue and subtle umber, the painting on the wall of Thomas Hawn’s office might easily be mistaken for an abstract effort. But where some see abstract shapes, Hawn knows exactly what he’s looking at: a depiction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis approaching a macrophage white blood cell.

In most cases, macrophage immune cells are responsible for engulfing and destroying harmful pathogens in a process called phagocytosis, but the tuberculosis bacterium is able to subvert that process and hide itself within the macrophage to avoid immune system destruction. Then it hides silently or begins to use the cell to replicate.

“It has all these strategies,” Hawn says of tuberculosis, the disease he studies as adjunct professor of Global Health and professor in UW Medicine’s Division of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. “That’s the biologic fascination: what in the world has this bug done to change the cell to no longer kill or recognize the bug?”

That biological adaptation is one of the reasons tuberculosis remains one of the most pressing public health problems of the 21st century as the leading infectious cause of death in the world. Spread by coughing or sneezing and exacerbated by crowded conditions and poor nutrition, it kills more than 1.6 million people a year. So why don’t we hear more about it?

Hawn says that’s partially because tuberculosis is a 21st century public health problem issue with a reputation rooted in the 19th century. Before a host of public health measures and the development of effective treatments in the 1950s curbed its prevalence in Europe and the Americas, tuberculosis earned an epoch-defining reputation as a “romantic disease” and “poet-killer” due to popular belief that its symptoms of slow physical wasting led to euphoric flowering of creativity.

Known by turns as phthisis, consumption, and the White Plague for the wan and wasting appearance of its sufferers, tuberculosis carried with it a sense of inevitable doom that lent itself to well to the era’s literary efforts. Novels, plays, poems, and no fewer than three operas featured the disease as a central theme or plot element.

The disease’s literary legacy can be ascribed to the fact that it touched all elements of society. TB wasn’t the disease of poets; rather, the poets and writers who contracted it were simply the ones most likely to reflect on and record the disease’s grim and unrelenting universality.

TB framed the 19th century. In 1804, one third of the deaths in London were from the disease, which reached epidemic levels in rapidly industrializing, haphazardly-planned cities.

Writing a century later in the early 1900s, Brazilian poet and tuberculosis patient Manuel Bandeira encapsulated his frustration at lack of effective treatments in the poem “Pneumothorax,” in which he asks his doctor if the titular medical procedure—then a novel development that involved an induced collapse of the lung—might prove effective. The poem concludes with the at-a-loss doctor replying: “No, the only thing to do is to play an Argentinian tango.”

A challenge for the 21st century

After his diagnoses as an 18-year-old in 1904, Bandeira would live another 64 years with TB—long enough to witness the development of effective drug treatments in the 1950s. Even so, more than a century later, Thomas Hawn shares some of poet’s frustration.

“We have good drugs and have had them since the 1950s—but good is in quotation marks,” he says. “They’re good because they work, but they’re not as good because you have to treat people for long periods of time.”

With more than 10 million worldwide suffering from active TB—most often characterized by fever, sweats, weight loss, and cough—addressing it on a global scale remains a challenge due to the six-month treatment period, the lack of a highly effective vaccine, inadequate diagnostic platforms, rising levels of drug resistant strains, and challenges in implementing interventions at a population level.

“If you want to treat the number of people who need to be treated, you have all these challenges of delivering medicine and getting people to stay on regimens,” Hawn says.

Progress toward expediting that process will be a central point of discussion at the 4th Annual TB Symposium to be held by the University of Washington Tuberculosis Research and Training Center (TRTC) on Monday, September 13 in Orin Smith Auditorium at UW Medicine’s South Lake Union campus. Hawn will deliver the introduction to kick off proceedings.

“Our goals for the TB Research and Training Center (TRTC) are to foster innovative research and collaboration among investigators to see how we can do more together,” he says. “We also want to give junior investigators opportunities to present their work, to network and meet people, to break down barriers for doing research.”

Hawn attributes the strength of the community of TB investigators in Seattle to greater emphasis in recent years on global public health by entities like the Gates Foundation, the Infectious Diseases Research Institute, Seattle Children’s, Fred Hutchinson, The Institute for Systems Biology, PATH, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), the Firland Foundation, several UW Departments and Divisions and UW’s institution-wide Population Health Initiative.

That’s on top of the UW medical system’s deep roots in the study of infectious disease—benefiting from what Hawn calls a “founder effect” due to the fact that many leaders in the early days of the Department of Medicine were infectious disease doctors. “The study of infectious disease has been a priority of the UW Medicine system for a long time and I think that tradition helped foster what we have today,” Hawn says. “At some point, you reach a critical energy.”

TRTC’s is a spirit of scientific collaboration and problem-solving that would make the poet Bandeira proud.

“We need major discoveries on a whole spectrum,” Hawn says, adding that he and his lab of investigators are as interested in discovering reasons why people don’t get infected when exposed as they are in what can be done when people do contract TB. “We think there’s something special about their immune system, we’re trying to figure out what protects them and can we turn that into a new treatment.”

Developing faster, more effective treatments

While Hawn remains most interested in “upstream” discoveries to develop new treatments, he stresses that the community of TB researchers in Seattle is actively trying to address all elements and iterations of the disease. The ultimate goal, he says, is to develop faster, more effective treatments that can be deployed the world over.

“It would be great if we could treat people for a week, a month—anything less than six months,” he says. “We could then deliver therapies that much more effectively and then either effectively treat the person who is coughing on other people and prevent them from transferring it to other people, silently infecting the next person, so the whole chain could be interrupted.”

Much can be done on a public health level toward improving the conditions that hasten its spread.

“The epidemic of TB is concentrated in urban environments where there’s a lot of crowding,” Hawn says. “It’s exacerbated when people are malnourished with weakened immune systems.”

But to eradicate the disease entirely, it’s necessary to examine its biological roots—the aspect of his work that Hawn says fascinates him most. Hawn’s hope is to one day discern which pathway TB is blocking to then find a way to activate that pathway so the pathogen can be eradicated.

“That area of new treatment is what I would hope 10 years from now would be part of a regimen that can shorten those six month treatment regimens,” he says, acknowledging that translating immunological discoveries into true intervention treatments remains one of his field’s greatest challenges.

“Right now,” Hawn says, “we’re still too many years away from tangible treatment outcomes.”

Science and fiction

Hawn’s work is driven by his belief that “our most important goals as humans should be to relieve suffering” and that “this journey of scientific discovery is really fun and it can be connected to practical, useful things.”

The study of biology, he says, helps him stay rooted in what is good and true in the world.

“When I get frustrated by the state of the world and how humans treat each other, I go back to the biology of life and that there’s something fascinating here to contemplate, discover, and investigate.”

Growing up in Cleveland, Hawn completed degrees at Princeton and Johns Hopkins before moving west for an internal medicine residency and infectious disease fellowship, which is where he began his investigation into the innate immune response to tuberculosis. When he feels stymied in his scientific research into tuberculosis, he does what countless others frustrated by the disease did before him: turn to art.

In addition to spending time with his family, running and climbing in the outdoors, and biking to work, Hawn is an avid fan of reading fiction to end his day. A few favorite authors include Toni Morrison, David Foster Wallace, and Thomas Mann.

“I feel like there’s something about the creative world of reading fiction that connects really deeply with the creative world of scientific enquiry,” he says. “When I read a great work of fiction, it makes my mind work in certain ways that makes me think of new scientific ideas. So even though fiction and science seem like they’re opposites, I see them as wonderfully connected.”

For a disease defined in history by art as much as science, it would follow that one researching better treatments in search of a cure would be a student of both.

Thomas Hawn holds an AB from Princeton University and an MD and PhD from Johns Hopkins University. To attend the 4th Annual TB Symposium, registration is free, but required here.