Faculty Friday: Sonal Khullar

Khullar visits a museum in Lahore. In 2017, she presented at the inaugural Lahore Biennale—the first art event of its kind in Pakistan.

For some, traveling the world conveys a sense of freedom.

For Sonal Khullar, associate professor of art history at the University of Washington, however, the act of crossing borders all too often illustrates the strictures and stumbling blocks of globalism in the twenty-first century.

“One of the things I’ve noted is that we usually think of globalization as the freeing or opening up of boundaries of circulation,” she says. “But there are lots of ways that globalization has meant inequality and unevenness.”

In researching her next book, The Art of Dislocation: Conflict and Collaboration in Contemporary Art from South Asia, Khullar traveled throughout India and Sri Lanka last summer as part of a research fellowship from the American Institute of Indian Studies.

Her goal: meet with artists, critics, and academics to discuss contemporary art and institutions of art that have emerged in the last twenty years. But it isn’t always smooth going.

India has seven paramilitary groups alone, tasked with guarding borders and countering insurgencies and terrorism. Sri Lanka is still recovering from a two-decade-long civil war that ended in 2009. And when Khullar was invited to the inaugural Lahore Biennale, she was trailed by intelligence services—a common occurrence for citizens of India traveling to Pakistan.

“The point is that even if it’s difficult to access an area or region, that doesn’t mean there’s not art being made there,” Khullar says, emphasizing with circumscription how important it is that her writing on the subject not make a spectacle of violence, oppression, remoteness, or, indeed, her own access.

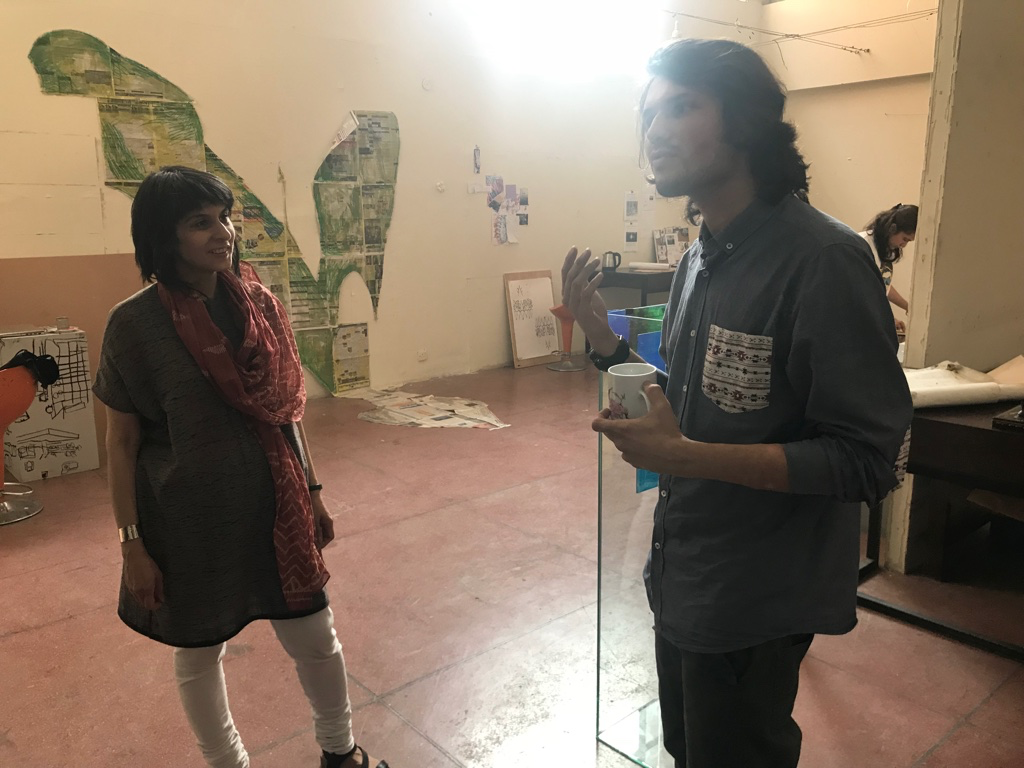

“I want to see how do artists live, what are their studios are like, what it is like to make art as an ethnic minority in a place like Sri Lanka in the wake of its civil war?” she says.

“Then I want to provide an art historical account that is, at the same time, ethnographic and attentive to the lives of artists and their dialogue with communities.”

Those communities are ones that might be described as local or regional, Khullar says, but which are in every sense as ‘global’ as a glittering venue for contemporary art in Paris or New York.

“One of the main arguments I’m making in this book about contemporary art is not only applicable to South Asia, but also to contemporary art globally: I’m thinking about art in the studio and the street as well as the gallery and museum.”

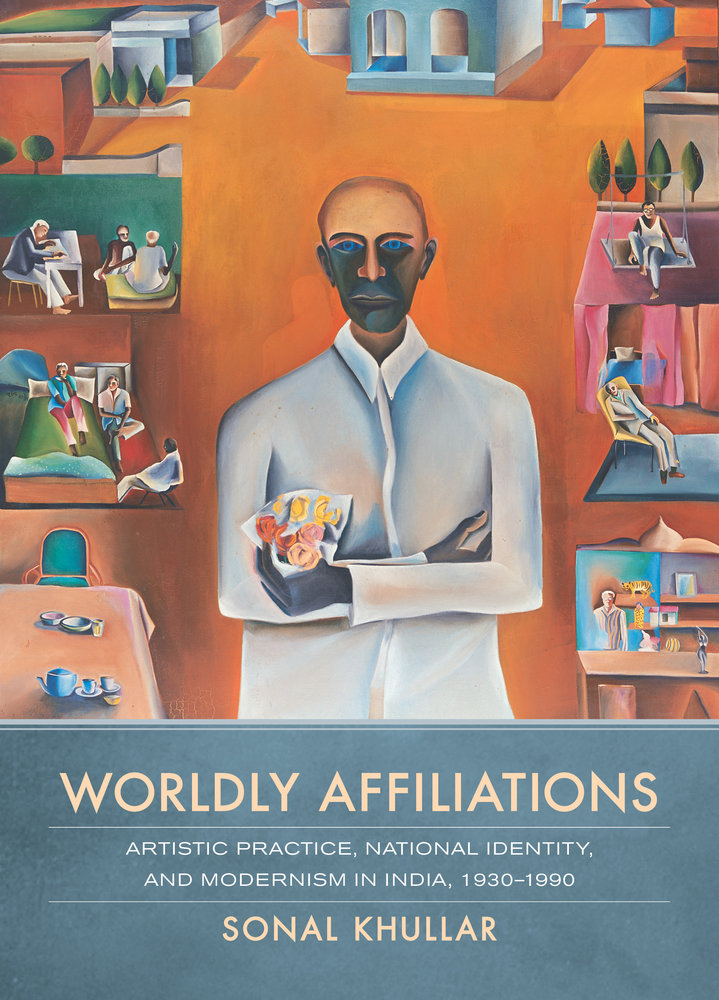

Through close analysis of original artwork, archival materials, artists’ writing, and period criticism, Khullar’s first book, published 2015, provides a vivid historical account of the state and stakes of artistic practice in India from 1930-1990, rendering visible the aesthetic and political achievements of Indian modernism.

Worldly affiliations

Khullar’s new project builds upon her first book, Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930-1990, which traced the emergence of a national art world in twentieth-century India, emphasizing its cosmopolitan ambitions and orientations. But now Khullar is looking at what has changed in the ensuing three decades—making the case that collaboration has emerged as a hallmark of contemporary art in South Asia and a critical response to globalization since the 1990s.

“The book has a two-fold focus: one on artworks, their aesthetics, and formal effects; the other a look at new systems of patronage and circulation for the arts—how audiences are seeing South Asian art in Europe, North America, and elsewhere in Asia.”

In some instances—often due to toughening of borders, even within nation states—artists have difficulty seeing each other’s work at all. But they’ve responded to this challenge, Khullar says, by creating new systems of creation, dissemination, and exchange, such as artist books, or by abandoning “object work” entirely in favor of far more ephemeral undertakings and modes of engagement.

“This work in many ways is not a reaction, but a reclaiming of space for dialogue and critique,” Khullar says. “We are seeing new developments in response to a history of 20th century art.”

The mediums and language of art are shifting at the rate of the globalized world. In the past, artists’ social and political commitment had been expressed in other ways.

Professor Sonal Khullar on a studio visit.

But now, many of the artists Khullar meets are doing art she describes as “socially engaged practice or social practice, which is to say, they lead workshops with citizens in their communities or create art through infrastructure projects such as building water pump sites or community centers.”

Khullar cites two works as particularly indicative of this new, discursive development.

The first involved the trappings of a funeral ceremony at a grave site that saw the artist climb into a coffin, which was then closed and interred for three hours, during which time she was recorded repeatedly writing on a piece of paper a word for “faith” with a red pen. At the given time, the artist was “disinterred.”

“Her arrival was like a funeral procession and then her departure was like one as well,” Khullar recalls.

“During the performance people sang, cried, and marked their solidarity with farmers who’ve gone missing in neighboring villages because of farmer suicides from debt.”

Known as the “agrarian crisis,” an estimated 300,000 farmers have taken their own lives in India since 1998—often the result of their inability to pay debts to microcredit banks who lend them funds to buy high-priced, high-yield seeds marketed to them by multinational agrochemical corporations.

When states’ failure to implement minimum support prices set by the Indian government, it only serves to compound farmers’ sense of despair at being wrung both ways by global markets.

The second artwork Khullar cites involved the crafting of a bamboo raft that sailed for several hours on the Brahmaputra River, an act intended to draw focus to issues of indigenous labor and the environment on the river.

“This art and these artists are deeply aware of history and not just social history—which is to say a history of immigration or the environment—but actually a history of art,” Khullar says.

“Much of this work is responding not only to contemporary developments—whether it’s farmer suicides or a booming art market—but also responding to a history of making.”

In tracing these new histories of art and systems of artistic exchange, Khullar has traversed cotton fields and tramped through coal depots. What she sees is a world responding to its collision with another. “What I’m going to argue in the book is we need to pay attention to these struggles around land, water, and the right to live in relation to art projects that are unfolding as these are crucial to understanding what globalization is and does.”

Two small fishing boats ply the waters of the Brahmaputra River at sunset near Sukleswar ghat in Guwahati, India. (Photo: Deepraj)

History loves company

In so many ways, Khullar’s upbringing was a product of those same globalizing forces that so defined the second half of the twentieth century. She describes her experience of growing up as one of “bouncing around the world.”

Born in Delhi, India, she moved with her family shortly thereafter to Arunachal Pradesh, a state bordering China, Burma, and India that is disputed between India and China. When her parents came to the U.S. as graduate students—her father studying to become an economist and her mother on her way to three graduate degrees in sociology, economics, and public administration—Khullar spent time in the Boston public school system.

“You become very conscious of and sensitive to various forms of difference,” she recalls of her youth. “But you also have a way of fitting in and belonging anywhere you go.”

Six schools in three countries—that was at the minimum, she estimates, before admitting she never really kept track. After Boston, the family returned to Delhi before moving once more—this time to the Philippines, where Khullar finished high school at the International School of Manila.

“We didn’t have a chance to think about moving all that much,” she remembers. “That was our life. People will still ask, ‘Did your parents keep your bedroom?’ and I say, ‘They didn’t even keep their own bedroom!'”

From Manila, she returned to the U.S. to attend Wellesley, where she took two “transformative” art history classes as a senior: one on feminist filmmaking, the other on Paris in the 19th century. Wishing to delve deeper into visual analysis, she applied to graduate programs in art history, landing at UC Berkeley where she got her Master’s and Ph.D. in the History of Art with a designate emphasis in Women, Gender, and Sexuality.

“It was a moment for me to start thinking about feminism—as an artistic and scholarly practice,” she says. “Feminism is an analytic you can bring to study absolutely anything—work by women artists or male philosophers or anything in between.”

Over time, Khullar’s interest in the visual arts became “a passion” and she grew to love writing about art as well: “That love of writing and of art has really intensified as my career has progressed rather than weakening, which is a very good sign.”

Her decision to specialize in the history of art in South Asia, Khullar says, was a decision she made early in her twenties, feeling long drawn back to that geography.

“I felt like I had questions about South Asia that I wanted answered—questions that seemed most immediate and that I felt best qualified to answer,” she says. “It was a feeling I think a lot of academics have: if not me, then who is going to do this work?”

To that end, she says she feels there are still not enough voices in modern and contemporary South Asian art history writing about the kinds of practices and movements she strives to chronicle. It’s a corrective Khullar hopes that, as an academic and educator, she can have some part in bringing about.

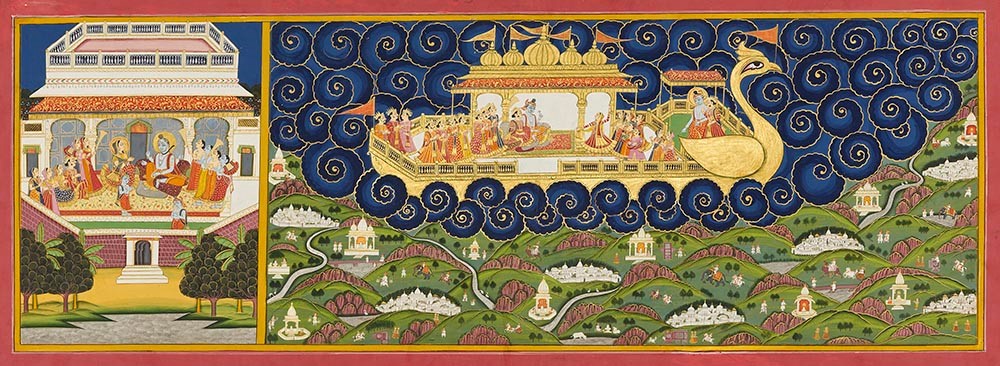

This fall—her tenth at the UW—Khullar is teaching a course that surveys the history of Indian painting from 1500 to the present in conjunction with the special exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum, Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur, India. The title is a reference to the Kingdom of Jodhpur’s place against the stark landscape of the Thar Desert in northwestern India’s Rajasthan state from 1226 to Indian Independence in 1949.

“It’s a chance to work closely with objects and have students interact with works of art firsthand,” she says, adding that the exhibition, which contains 250 art objects, many of which have never before traveled beyond palace walls.

On November 17 from 2-6 pm in Kane Hall, Khullar will host “Power and Pleasure in Indian Painting,” a symposium at UW and offshoot of the SAM exhibition with an emphasis on Indian painting in Mewar and Marwar—distinct areas of Rajasthan ruled by Rajputs (Hindu kings)—and the Mughal empire between the sixteenth century and nineteenth centuries.

As part of the event, speakers with expertise in painting from Mewar (Dipti Khera), Marwar (Debra Diamond), and Mughal India (Yael Rice) will discuss connections and disjunctions between Rajput and Mughal painting, illuminating the intricate web of collecting, connoisseurship, cosmopolitanism, and cultural exchange among courtly elites.

“This show will be much more focused on the 17th through the 19th century, so it’s also a chance for me to broaden my teaching and research,” Khullar says. “Painting is my first love so it’s going to be a great pleasure to get back to that.”

One Thought on “Faculty Friday: Sonal Khullar”

On October 26, 2018 at 5:51 PM, Barclay said:

Art museum exhibit looks great. Enjoyed the imbedded link to it.

Comments are closed.