Staff Story: Stacie Louviere

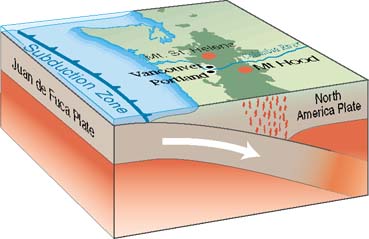

Last October, a University of Washington research team presented a study at The Geological Society of America’s annual meeting in Seattle that simulated 50 different scenarios for a magnitude-9.0 earthquake on the Cascadia subduction zone—a large rift in the Earth’s crust 50 miles off the Pacific Northwest coast. There, the Pacific sea floor of the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate sinks beneath the North American plate to produce one of the world’s most dangerous earthquake faults.

Stretching 600 miles from Cape Mendocina in Northern California to Canada’s Vancouver Island, the Cascadia subduction zone has produced at least 20 magnitude 9 earthquakes over the past 10,000 years. When the last one occurred 318 years ago, it sent a tsunami crashing against the Washington and Oregon coast that was felt as far away as Japan.

When the next subduction zone earthquake will occur can’t be predicted, but geological odds say the chance of a “Big One” is not a matter of if, but when. That analysis could strike some as a grim inevitability—cause for resignation in the face of assured eventual catastrophe. But one UW staff member is educating against that tendency: Stacie Louviere.

Since September 2015, Louviere has served as the UW’s first Seismic Resilience Program Manager, part of a larger four-person Emergency Management team who work year-round from an operations space on the ground floor of the UW Tower.

“At the end of the day, [the severity of a major earthquake] is going to depend on where exactly that earthquake hits and how strong it will be—neither of which I can tell you,” Louviere says.

What she can tell you is how to prepare in case of such an event—something she does monthly in the form of Earthquake Awareness and Personal Preparedness seminars across the UW. At the talks, Louviere discusses earthquake risks specific to the Puget Sound, personal preparedness basics, and what an earthquake response should look like at the UW.

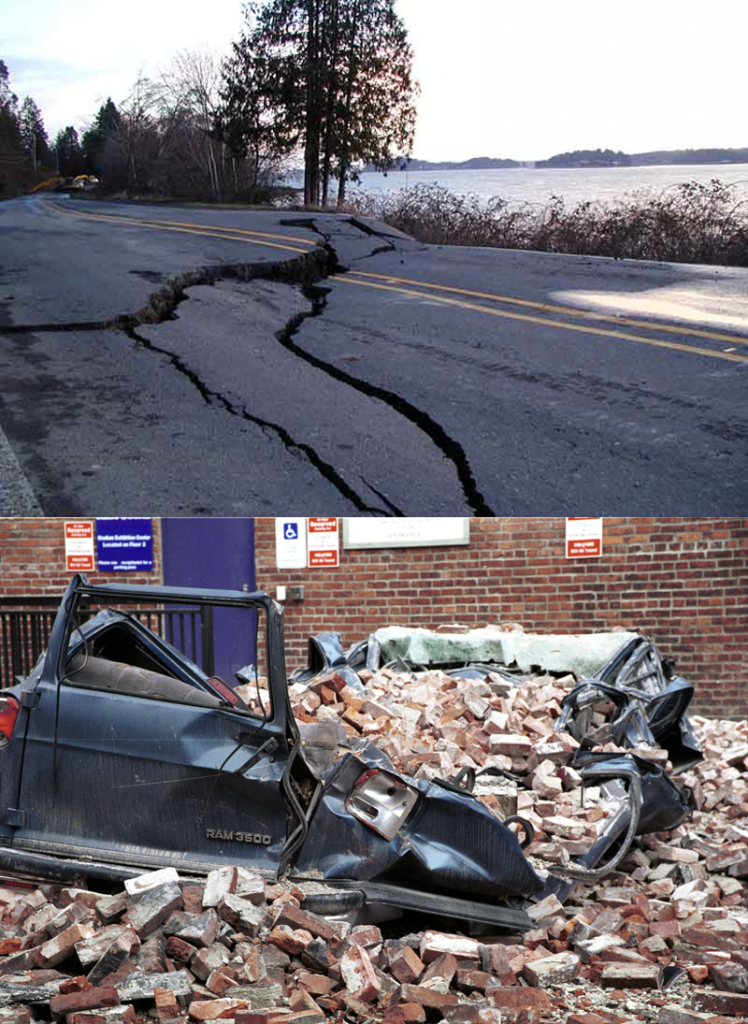

Damage from the 2001 Nisqually earthquake.

“When the shaking is happening, you’re not going to know what type of earthquake it is, or if there are going to be aftershocks,” she says. “So while I can give you a little bit of science and fact, my main message and purpose is to outline the risks of what’s possible, but also what you need to know to be prepared and be safe.”

Great shakeup

The region’s last major earthquake—the Nisqually quake in 2001—clocked 6.8 on the Richter scale, damaging roads and buildings and injuring hundreds (there was one fatality, a heart attack).

Louviere says that while another earthquake at that level would hardly be ideal (the average duration of strong shaking during a “big” earthquake in Seattle would be about 100 seconds—about four times as long as during the Nisqually quake), it would raise awareness around the steps one can take to be prepared.

At the University level, Louviere says the key element of emergency response is communication: “Knowing who to call and who has the authority to say what.”

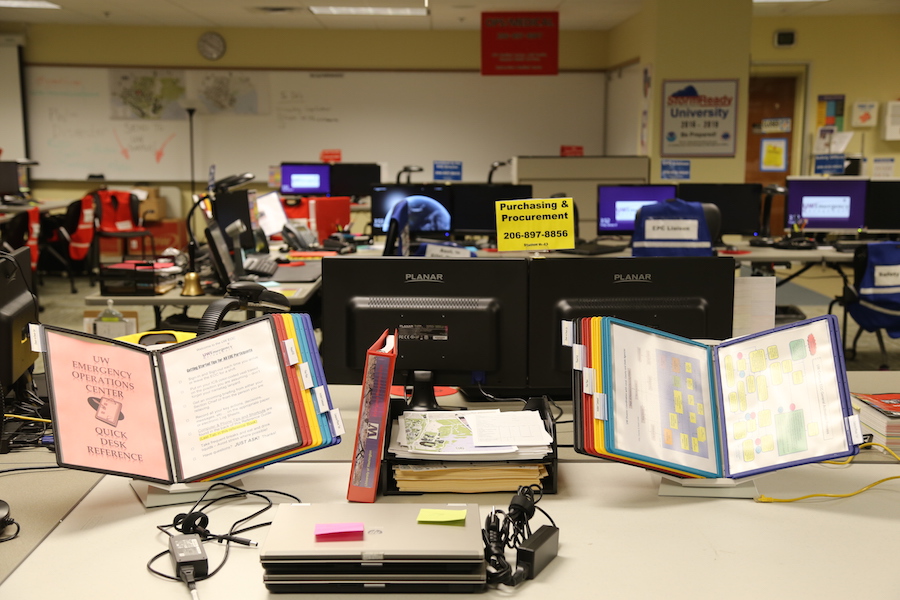

Twice a year, stakeholders and decision-makers from across the UW take their places in the UWEM space at the UW Tower and stage a mock-event response exercise.

“That response process is going to be the same regardless of the scenario,” Louviere says. “That’s why we call it the Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan and used to call it the All Hazards Plan: it doesn’t matter why you might be stuck on campus for the next two weeks; you’re going to need the same provisions and decision-making abilities to be able to sustain yourself here.”

There are few better places to be in the event of an emergency than the UW—whether it’s an earthquake, flood, or other emergency. “The number of universities in the country that have a standing, 24/7 operating, emergency operations center are very few,” Louviere says of the Emergency Management space, which also serves as the backup space for the Seattle Emergency Management Office downtown.

“For example, not many campuses have designated resources—including people who are trained—to assess the hazmat conditions inside of buildings. That’s huge,” she says, referencing the “Pre-Entry Assessment Team” (PEAT), supported by Environmental Health & Safety.

Also contributing to the sense of autonomous expertise are teams of engineers known as ATC-20 teams who are certified by the city of Seattle to tag buildings after an earthquake as to whether it is safe or not to enter—another rarity on campuses nationwide.

Louviere says the key element of emergency response is communication: “Knowing who to call and who has the authority to say what.”

Louviere’s own interest in Emergency Management developed as she studied for her Master’s in Infrastructure Planning and Management (MIPM) at the UW after graduating with a bachelor’s in Political Science and Economics from Western Washington University.

While studying at the UW, Louviere trained in understanding of infrastructure systems with an eye to increasing resiliency and sustainability within each system in the wake such events as civil unrest, terrorist acts, extreme natural events, climate change, and other, more common accidents.

“I always had a desire to work in a space dedicated to public health or local government,” Louviere says, adding she never imagined she’d be working in her current capacity, partnering with UWPD, Environmental Health & Safety, Housing and Food Services (HFS), UW-IT, and other campus partners throughout the year alongside her Emergency Management colleagues in the work of assessing the likelihood of any number of scenarios and plotting corresponding emergency response plans.

“In the field of emergency management that’s literally how we do our job: asking what are the threats, what could possibly go wrong, and then looking at the likelihood and potential damage,” she says. “Our top priority is people are prepared and know what to do in any situation, what the risks are, and how to be ready for them.”

Every person’s personal preparedness counts in sum total towards everyone’s overall safety.

“In an emergency, you never know who the most important person might be.”

Catch Stacie’s next presentation on Thursday, February 15 at the UW Tower Auditorium.

Upcoming presentation dates:

March 15 – HUB 250 – 2:00 p.m. – 3:00 p.m.

April 11 – Alder Hall Auditorium – 12:00 p.m. – 1:00 p.m.

May 18 – Facilities training Center – noon – 1:00 p.m.

June 19 – Kane Hall Rm 110 – 6:00 p.m.-7:00 p.m.

August – Allen Auditorium (day and time TBD)

September 14 – UW Tower – 10:00 a.m.- 11:00 a.m.