Faculty Friday: Megan Ming Francis

In 1999, Megan Ming Francis left home in Seattle to study computer science at Rice University. Her plan was to see the world, then someday return to Washington to work for Microsoft. Fifteen years later—after subsequent stopovers in New Jersey, Illinois, Indiana, and California—she was back, but instead of a career as a computer programmer, she’d become a leading political scientist, specializing in the study of American politics, race, and the development of constitutional law.

So what changed?

“After a year, I bought into the belief that college should be a time for you to explore new interests and figure out what you want to be in life,” Francis says. “Econ and political science helped me understand the world around me better. I could understand things like going to a high school with extreme economic inequality, why some classmates had things while others did not, as well as political and economic inequality in my own life. I found that empowering.”

Today, Francis is an associate professor of political science at the University of Washington. Next Wednesday, she’ll deliver her second public lecture in a three-part series on contemporary rights movements.

“What I want to do in the lecture is to problematize our discussion on immigration, walls, and borders specifically in the post-9/11 moment,” she says. “For me, what struck a personal chord was the Muslim ban/travel ban that came down shortly after Trump assumed the presidency. I think a lot of people knew that was wrong, but I don’t think many people understood why it was so wrong.”

She plans to approach the topic from an academic standpoint as well as a personal one: “My mom was born in a refugee camp [in Korea] and my father is a Jamaican immigrant and both were UW students who met at the University of Washington.”

Presented through the Graduate School, the lecture forms part of the UW’s weeklong celebration of the life and legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. as well as the generations of activists who’ve agitated for a more just and equitable future.

Ask Francis about it and she’ll make a point of emphasizing the unsung activists of the past in particular. Progress in the cause of civil rights has always been hard-won, she says, yet those stories are often brushed and burnished into an easy-to-consume narrative bookended by Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

“What you get is a nice, compact history that tells us the Civil Rights Movement is ultimately short—a ten year narrative at some level—and that this country and our government institutions respond when people let them know that things are going wrong,” she says.

As a political scientist and student of history (at Rice, she was two electives shy of triple majoring in history in addition to political science and economics), Francis is most interested in the stories that speak to the fight for civil rights in the years before the federal government got responsive.

“The long history of people of color organizing in this country has never been one of things happening quickly,” she says.

Dr. King once offered that, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Francis would contend the cause for that curvature is thanks to the agency of civil rights activists who’ve persisted in building upon a decades-long history of setbacks and achievements.

“What happens if we look to the reality that this is a much longer movement? The mobilizing that happens in the ’60s plays off the ’50s’ Brown v. Board, which itself is a culmination of an education segregation litigation campaign that started in 1931. The litigation strategy that was developed in 1931 basically came from the NAACP beginning in 1909 and the reason that comes about is thanks to the organizing of Ida B. Welles in 1896.”

“That, all of a sudden, becomes an 80-year history.”

For Francis, forming so enduring a commitment to justice and ally-ship is a question of, “Are you in it for the long haul?” But all too often, people aren’t.

As a graduate student at Princeton, Francis finished her dissertation on racial violence in the United States on the eve of Barack Obama’s historic election victory in November 2008.

“What happened in 2008 was that Obama is elected as the first black President of the United States and this exciting moment sweeps across the country and obviously touches academia—including my field of political science and American politics,” she recalls. “Many people were in this post-racial moment—this turning of the page in this horrible history of race in American politics.”

Poised to enter the academic job market, Francis says few departments at that time were willing to address the historical realities of racial violence in the United States: “People were like, ‘why are you talking about lynching and mob violence?’”

“The rush and desire to push past so many of this country’s demons and not deal adequately with them is fascinating to me,” she says, adding that people’s eagerness “to latch on to these celebratory narratives—these easy short cuts is stunning.”

History is as much about asking hard questions as it is about one’s willingness to confront the difficult answers it holds in store—such as the overt campaigns of racial violence and domestic terror that blighted black lives and communities across the United States from the end of the civil war well into the first half of the 20th century.

“I don’t think that’s something a lot of people are trying to deal with,” Francis says. “You cannot appropriately fight for racial or social justice without looking back—it’s literally impossible.”

Francis points to one case in particular as having been instrumental to the revolution in criminal procedure in the 1930s and 40s that set the stage for civil rights victories in the decades to follow.

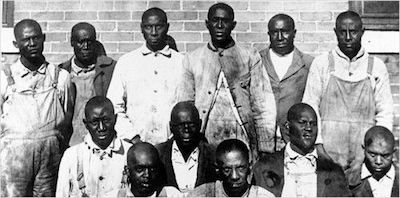

The 12 men indicted after 1919 Elaine, Arkansas riot. It is estimated over 200 African Americans were killed along with five whites during the hysteria of a pending insurrection of black sharecroppers after 100 attended a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church to organize to obtain better payments for their cotton crops. (Public Domain)

Following in the wake of the prosecution of twelve men for the death of a white man that sparked a 1919 race riot in Elaine, Arkansas that saw the deaths of five white men and an estimated 100 to 237 African Americans, 1923’s Moore et al. v. Dempsey was the first case to come before the Supreme Court in the 20th century related to the treatment of African Americans in the criminal justice systems of the South.

The Court ruled 6-2 that the defendants’ mob-dominated trials violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, establishing a precedent for the Supreme Court’s review of state criminal trials in terms of their compliance with the Bill of Rights. The case made clear that states could not always be trusted to administer matters of criminal procedure and that federal courts could intervene when state courts failed to uphold rights.

“Before this case, federal courts stayed out of state trials [and] different states had different criminal court trials,” Francis says. “It’s absolutely a watershed moment—a landmark Supreme Court decision that I don’t think has gotten its due.”

The effort that culminated in Moore v. Dempsey, Francis says, exemplifies how the NAACP created opportunities for black civil society to challenge Jim Crow through criminal courts and ultimately pushed the federal government in a new direction.

Flash-forward to the present and Francis says “being attendant to the past…dealing with it in all its ugliness—not just in terms of how racist, how sexist, how nativist many of the institutions in this country have been—but also asking how do we survive and move past this” is one of the keys to moving forward to a more just society.

“One of the big lessons we can draw from it is that there’s not one institution that is going to be the guarantor or protector of rights,” Francis says. “I think that’s an important lesson for activists and people interested in justice today: some people focus on politics or some people focus on courts, but you shouldn’t put all your marbles in one basket.”

What’s heartening for Francis is the number of individuals who have channeled the energy of demonstrations and public protests of the past year into engaging in politics at the local level.

“Seattle is an amazing case study of that in terms of the Peoples Party and watching what Nikita Oliver has done in terms of running [for mayor],” Francis says. “A lot of justified anger that you saw on the streets is now being channeled into saying, ‘Okay, let’s run and change things; let’s see if we can actually win offices in government and change things and have a stake at the decision-making table.’ I think that’s powerful.”

For Francis, “the past can light a way out of the present darkness”—however dark that past might be.

Megan Ming Francis has a B.A. in Political Science and Economics from Rice University and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Politics from Princeton University. Her book, Civil Rights and the Making of the Modern American State was winner of the 2015 Ralph J. Bunche Book Award for the best scholarly work in political science that explores the phenomenon of ethnic and cultural pluralism and winner of the 2015 W.E.B. Du Bois Distinguished Book of the Year Award, National Conference of Black Political Scientists.