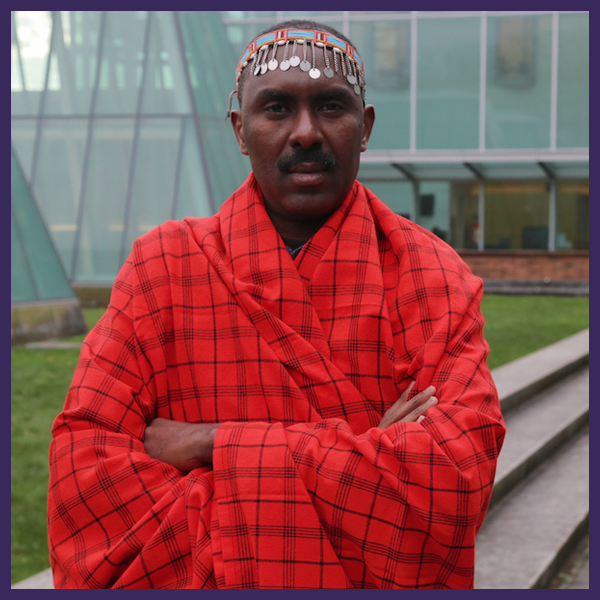

Staff Story: Hassan Guyo

When Hassan Guyo stopped running two years ago, it was a strategic move in the race of a lifetime.

He’d just started taking classes at the UW School of Law and would soon begin work as a custodial supervisor for the UW Facilities and Building Services Department. With a wife and four children at home in Seattle’s Maple Leaf neighborhood, he’d spend time on weekends tutoring students in the neighborhood and was about to start serving on Seattle Public Schools’ Equity and Race Advisory Committee to the Superintendent. It would be his second such appointment, having already spent several years on the Seattle Police Department’s advisory committee on issues affecting East African immigrants and refugees.

Outwardly, Guyo’s life appeared firmly rooted in Seattle, but for all his community commitments, his heart lay elsewhere, far from Puget Sound. He’d never forgotten his mother’s parting words when he left Kenya for the United States more than a decade before: “Do not forget where you come from.”

Yes, running had to go. It had gotten him this far, but the next several years would be the final sprint on an out-and-back course that spanned an ocean and two continents. It would require his full focus and all the energy he could muster.

Guyo’s journey began on a small cattle farm in a remote rural village in northeast Kenya’s Isiolo County. Educated in his father’s Maasai warrior-herdsman tradition, he learned to herd goats and cattle, while training to hunt lions, leopards, and hyenas with bows, arrows, and a spear—gifts he received from his father, who passed away when Guyo was a young teen.

Thereafter, Guyo and four siblings were raised by his mother, the village’s midwife and herbalist, who would often take him along with her when she went out to deliver babies in the dead of night. After a long day, she’d gather the family around the fireplace to tell stories.

“She’d always begin by saying, ‘I see hope in the future,’” Guyo recalls. “That inspired me to really help and reach out to others who are less fortunate.”

Like many Kenyans, Guyo grew up running track and cross-country, competing in middle- and long-distance events in high school before being offered a scholarship to attend college at Concordia University in Minnesota. His tuition was covered by the school, but his plane fare was not, so his mother and several village elders organized a fundraiser to send Guyo to the U.S.

“When I left my village, I took this journey not for myself, but for the service of others,” he says. Fifteen years later, Guyo couldn’t find himself farther from home—or closer to an ultimate return.

Journey to the West

Ask Guyo about his role as UW Combined Fund Drive coordinator for the Facilities and Building Services Department last year when he and a team of 21 participants raised more than $2,700 and he will tell you a little goes a long way. He would know. He arrived in Minneapolis in 2004 with little more than the $50 in his pocket.

“My end goal was to go back home and make a difference in my community,” he says.

But before that, he had to find a job to cover his daily expenses as a student-athlete at Concordia. He worked as a custodian, delivered items around campus, and—just as many college students do—found work in the library.

“That really helped.”

And, just as many college students do, he fell in love, having been introduced to his future wife by a mutual acquaintance in Kenya. There was one hitch—she lived in Seattle at the time. But the inconvenience would prove only temporary.

After dating long-distance for a spell, Guyo moved to join her in Seattle in 2007, transferring his college credits to Evergreen College in Olympia where he completed his B.A. in Economics and Business Administration.

“I want to use this moment to really make a difference; to work on something larger than my own life,” he says. “My end goal, really, was to get my law degree, go back home, and do something around social justice, human rights, issues around women’s rights, health issues, and economic development.”

With an athlete’s mindset, Guyo determined the most effective way of eventually impacting his own community in Kenya was to get practice doing the same type of work in Seattle. Living in Rainier Valley at the time, he became active in the area’s migrant African community as an advisor and tutor.

“I’ve worked on a lot of issues affecting children, children’s rights, women’s rights, social justice, indigenous people’s rights, land rights—these are issues very dear to my heart,” he says, adding that his own background as part of Kenya’s indigenous population has informed his perspective state-side. “Native people, indigenous people—you have to fight for your own survival.”

Some eight years after moving to the Seattle area, Guyo found there was “no perfect place better than law school” to examine the issues he cared about most.

“I took a few classes and liked it,” he says of his pivot to life on the UW’s Seattle campus. “When I moved here, I was really inspired.”

Guyo says his pursuit of a Master’s in Sustainable International Development Law—the first graduate program at a U.S. law school to focus on international development law—is a means to another end. The outcome won’t be to practice law.

“I can use that law degree to make a difference—a difference in a different way. It’s using that law degree to expose issues of corruption back in Kenya; of creating awareness.”

To assist with tuition, he started working as a custodial supervisor 2 in the UW Intercollegiate Athletic Department before transferring to the Facilities and Building Services Department where he now supervises 30 custodians.

“People are very supportive around here,” he says. “There’s a sense of community and belonging—of moving together.”

His is a dual perspective of both staff and student. His days start on campus at 4:30 a.m. When work wraps at 1:30 p.m., he heads to the Law library to read and study before classes start in the evening.

“Sometimes, I’ll leave the library at midnight,” he says. “It’s tough schedule to manage, but I’m used to that.”

He says he realizes the custodians he manages have tough schedules as well, often commuting long distances to work in addition to sometimes holding other jobs.

“I think they work really hard in spite of the language and cultural barriers,” Guyo says of his team, adding that while UW is a place defined by “community, compassion, and understanding” with “many resources and opportunities to grow and develop,” the current socioeconomic climate in Seattle places many burdens on lower-income workers.

“Seattle is booming and housing availability is almost out of reach for most refugees, immigrants, and low-income people,” he says. “I know most of my staff of custodians are migrant workers and they’ve moved out of Seattle to places like Tacoma, Burien, Federal Way. They live far away and have to drive to campus. To get here can be very time-consuming and difficult.”

“These are the struggles that, as a supervisor, I realize I see,” he says. “Those are the things that frustrate me a lot.”

Even so, he calls UW a “home away from home”—a launching pad for his own hopes of ameliorating the issues of disease, poverty, and environmental degradation that blight his own village in Kenya and the country at large. Since coming to the U.S., he lost two siblings and his mother to malaria. More recently, he’s been able to return home about once a year—serving as an advocate and mediator for his village in its dealings with the government. When he does go back, he doesn’t always recognize it from past visits.

“It’s heartbreaking when I go there,” he says. “People cut down trees, burn charcoal, and sell wood to people living in cities. When I was growing up, there were big forests. Now, everything is cut down. I cannot believe that’s the place I grew up.”

In Kenya, rural community lands cover two-thirds of the country’s land area, yet only around 6% of the country’s land is formally designated for or owned by local communities—much lower than the global average of 18%. Additionally, as of a 2015 study, the country’s forest cover is less than 7% of total land area—well below the constitutional requirement of 10%—with deforestation estimated at 50,000 hectares annually.

As short-term economic pressures continue to diminish woodlands, forests’ role as natural “water towers” for outlying areas is significantly reduced, causing rivers to dry and compounding issues of population health, hunger, and economic insecurity nationwide.

As short-term economic pressures continue to diminish woodlands, forests’ role as natural “water towers” for outlying areas is significantly reduced, causing rivers to dry and compounding issues of population health, hunger, and economic insecurity nationwide.

Once he graduates from UW School of Law this June, Guyo, who is fluent in Swahili, Arabic, Urdu/Hindi, and Oromo, plans to redouble his outreach efforts, returning more often and for longer stretches at a time. He’ll start at home and go from there.

“I’m very optimistic things will change, but there should be a concerted effort to really make a way forward,” he says, adding that a fresh approach is needed in Kenya, currently mired in a political crisis.

Whether on the local level in Seattle or nationally in Kenya, Guyo says it’s about turning adversity into opportunity. Like his mother before him, he sees hope in the future.

“Hope is a good thing.”

Hassan Guyo holds an M.S. in Justice Studies with a concentration in Public Administration and Policy from Southern New Hampshire University and a B.A. in Business Administration from Evergreen State College. He is currently enrolled in the Masters in Sustainable International Development Law at the University of Washington School of Law.

2 Thoughts on “Staff Story: Hassan Guyo”

On November 18, 2017 at 3:59 PM, Job Ombati said:

Guyo is my brother. Any Kenyan who knows him knows that he is a true patriots and I wish him all the best in his endeavor.

On November 21, 2017 at 4:23 PM, Jennifer Simpson said:

What a moving story. Mr. Guyo sounds like a truly dedicated person, and best of luck in his journey to improve conditions in Kenya and raise environmental awareness.

Comments are closed.