Faculty Friday: Michelle Martin

For Michelle Martin, the Beverly Cleary Professor for Children and Youth Services at the University of Washington’s Information School, reading’s best lessons aren’t found in the book, but in the binding.

“Sharing books is as much about relationship building as it is about skill development,” she says of literature’s connective quality. “There’s a difference between reading a story and telling a story. There’s this immersive quality when you are there with the storyteller.”

That live-out-loud quality defined Martin’s life long before she made a name for herself as an author, critic, community activist, and champion of diversity in children’s literature. Growing up in what she describes as a “middle-middle class African American neighborhood” in Columbia, South Carolina, Martin recalls classroom activities such as memorizing poetry and contests of rhetoric as having had a greater impression on her than reading any particular book in class.

“A lot of things were turned into drama. We always had really big productions for Black History Month,” she says of her experience at Greenview Elementary School. “I wouldn’t say our school had an Afro-centric bent to it, but that’s who was there: 100 percent black kids.” All the teachers, she says, possessed a strong sense of “letting these kids know where they came from and what they’re history is.”

At home, Martin’s family placed a high value on literacy. Her grandmother was a kindergarten teacher and only a few credits from finishing her Ph.D. when she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

“When you think about the fact that would have been in the 1950s and 60s, for an African American woman to have that sort of education, it was pretty unusual,” Martin says. “And phenomenal.”

Even with her family’s academic pedigree, Martin’s focus from a young age was elsewhere—and that usually meant the outdoors.

“I wasn’t the kid reading under the covers with a flashlight.”

Instead she was out earning a Gold Award as a Girl Scout in high school and, after majoring in English as an undergrad at William and Mary, embarked on a five-year career as an outdoor educator, during which time she served as a naturalist at Sesquicentennial State Park in South Carolina’s Sandhills region.

It wasn’t until well into her adult life that she first thought about children’s literature seriously. She describes a path-changing encounter at Northern Illinois University where she was pursuing a master’s in Outdoor Teacher Education. Listening to a professor read aloud from Tuck Everlasting as part of a one-off literature class she was taking, Martin was moved when he “broke down in tears because of the beauty of the language.”

“I was like, ‘Wow, if there’s that sort of power in these books, I want to know more.’”

Based on that experience, Martin decided to embark on an independent study to produce a curriculum guide for teachers called Branching Out aimed at integrating books with outdoor themes into what students were learning in literature and history. The project would prove the kernel for Read-a-Rama, a program Martin founded in 2001 to help underserved students ages four to 11 connect with reading in ways they might never have thought possible by placing books at the center of a host of activities organized around a certain theme. After running it for eight years as a semester program, Martin organized the first multi-day summer camp in 2009 around a theme of water and heat, dubbing it, Columbia Summer Sizzle.

“We took them swimming, we taught them about the scientific properties of water, we brought in a watercolorist to teach about how to paint with watercolors, we took them to see glassblowing so they could see how heat works,” she says of the program’s first full summer slate of activities, another hallmark of which is that all participants receive a free book.

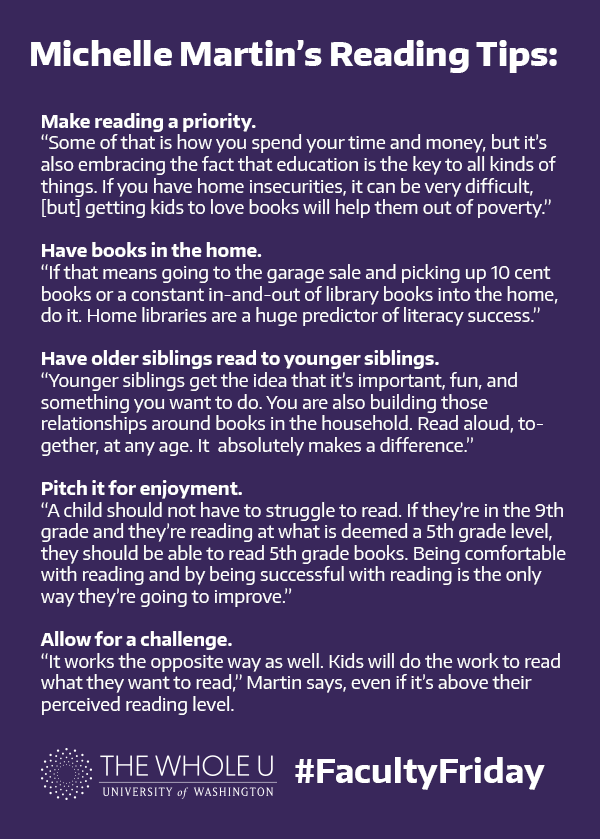

A recent study by the Packer and MacArthur Foundation found that the average middle class child logs 1000-1700 hours of one-on-one picture book reading against the low-income child’s 25 hours—nothing short of an egregious gulf in access and opportunity.

For Martin, her work is about reducing the distance between books and life as children live it.

“It’s a way to take puppetry and poetry and science and music and art and literature—throw it all into the same pot with books and teach kids how to live books,” Martin says. “It’s showing kids in a hands-on way that for anything you do in life, there’s a book that might be about that, and for any book you read, there’s something you can do to help deepen your experience of that book.”

Camp Read-a-Rama ran for five years at Clemson and for two at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, overlapping two summers. This coming summer in Seattle, Martin plans to run reading camps for two-and-a-half weeks—one for about 35 children at an affordable housing complex for formerly homeless families and another for young adults at the Gethsemane Lutheran Church downtown.

Martin’s outreach specifically targets areas with high populations of low-income students who are especially susceptible to “summer slide,” the three month period where many tend to lose ground academically. She says her hope is that Read-a-Rama one day serves as a national model for literacy engagement camps for children.

“We’ve had this program in a very rural area and in an urban area that is nowhere close to the size of Seattle, so this will be a third habitat very different from the other two,” she says. “I’m really excited to see how it will work.”

Missing Pages

Children’s literature, for all its whimsy and innocence, still bears countenance to issues of marginalization and race at work in society today. Many traditions of minority literature find their origins in stories written for the entertainment of a white readership before “champions from within” were able to reclaim it as their own.

For Martin, this literary history of appropriation and ignorance limits minority populations from the imagination and growth that comes from being able to see oneself reflected in the world.

“We need diverse books in which children can find reflections of themselves,” Martin says, referencing renowned author and children’s literature scholar Rudine Sims Bishop’s seminal “Mirrors, Windows, and Doors” thesis, which holds that children’s literature should be a mirror in which children can to see themselves reflected, a window through which they can see other worlds, and a sliding glass door so as to allow readers to enter such worlds.

Martin says that with time reading options have become “more and more colorful and diverse,” but there persists what she dubs a “pipeline problem.”

“Almost everybody publishing children’s books, almost everybody on the award committees, almost everybody in librarianship—all those pipelines involved in getting children’s books into children’s hands—are still largely white,” Martin says. “We’re not out of the woods yet.”

Martin is at work on a book about the two “fathers of African American children’s literature,” Langston Hughes and Arna Bontemps, who, as part of Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, created a large body of work for children celebrating African American life, much of which remains unpublished to this day. Resurfacing such texts is essential not only because they are seminal classics, but also because they provide a new context for how African American life is typically portrayed in what books do exist.

“If you remove from African American children’s literature all the books about civil rights and all the books about slavery and all the books about important historical figures, you’ve got a very paltry pile left,” Martin says. “You miss the daily-ness of being a black child. There need to be a lot more representations of kids doing what kids do.”

To bridge the gulf created when publishing’s gatekeepers refuse to break the exclusionary molds and models they’ve established and to which they, by and large, unswervingly adhere, Martin says many authors and illustrators are creating their own presses and books to get their work into the world.

“Sometimes it’s the commitment to getting those stories out there for the writer that’s more important than that it’s going to be turned into a movie,” she says. “Stories are the building blocks of expression, and you really change the culture when stories drop out of the picture.”

Wizards, Whangdoodles, and Whizzpoppers

Wizards, Whangdoodles, and Whizzpoppers

It’s a do-it-yourself spirit of outreach and connection that Martin also finds so alive at the iSchool, which she calls, “second to none.”

“Much of what goes on at the iSchool has direct implications for those in the community—whether that’s down the street at the local library or in a computer lab in Puyallup,” she says. “Intentionality and impact has always been a part of this unit at University of Washington.”

This quarter, Martin is teaching “Multicultural Resources for Youth” and next quarter will teach “Intellectual Freedom” and “History of Children’s and Young Adult Literature.” She says the diverse stories, perspectives, and insights her students bring to this quarter’s class have been “phenomenal.”

“It’s taking me a long time to grade their work because they’re taking me in different directions every posting.” Not that you’ll find Martin complaining. “I’m having a great time. I love classes that stretch me.”

This summer, Martin plans to stretch far indeed—leading a study abroad program to Great Britain, titled “Wizards, Whangdoodles, and Whizzpoppers” after elements found in the work of famed British children’s authors J.K. Rowling and Roald Dahl.

“My goal is to not only give them a good dose of traditional Anglo-British children’s literature, but also to bring them into the 21st century and learn about the diverse authors who are publishing British literature now,” Martin says, adding that in addition to helping hosting several Read-a-Rama programs in London, Cambridge, and Newcastle, students will visit libraries, literary sites, theaters, and spend “significant time in archives.”

And that will just be her first year here.

Moving forward, Martin plans to keep outreach front and center through teaching, Read-a-Rama camps, and pushing students into the community, “especially into diverse areas where they might be less in their comfort zone.”

She also says she looks forward to working with librarians statewide and nationally “to make sure

students here are well-equipped, culturally competent, and excited to work with kids and communities.”

While Martin’s major goal is to diversify people’s thinking about the histories of children’s and young adult literature, she recognizes her own limitations. She says that while her own cultural competence is strong for African American literature, she will work to bring experts to campus whose insight into other children’s literary traditions better and more broadly reflect the cultural milieu.

“I’m able to teach librarians who are going to put books in children’s hands who are now going to know a totally different canon than I grew up with because I’m doing this at this level,” Martin says. “That’s pretty exciting.”

It’s the cross-generational impact of her work Martin finds most invigorating— whether that’s on a scholarly level, at a student camp, or in her own home. At night, she and her husband still make a habit of reading together with their 13-year-old daughter. Reading with mom has recently entailed cracking the spine of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, while reading with dad tackles The Grapes of Wrath.

“That is not a book I would recommend for a 13-year-old,” Martin says, but it is one she says her daughter might not have picked up on her own. “If there’s a parent or sibling reading with them to bring them into this other story, it absolutely makes a difference.”

For Martin, the difference is clear.

“I wasn’t a kid who ate books as a child. I have a child who eats books now. That does my heart good.”

Michelle Martin has a B.A. in English literature from the College of William and Mary, a Master’s in Outdoor Teacher Education from Northern Illinois University, and a Ph.D. in English from Illinois State University. Learn more about Read-a-Rama here.

Wizards, Whangdoodles, and Whizzpoppers

Wizards, Whangdoodles, and Whizzpoppers