Satisfy Your Sweet Tooth: Natural Sugars

It’s probably better to skip dessert, you tell yourself as the waiter brings the check, but let’s just take a peek at the menu.

Soon you’re three spoonfuls into a bowl of vanilla ice cream, and there’s a triple-fudge brownie waiting patiently for your attention. You smile in delight with each bite, then twinge with regret for your poor belly. Months from now you’ll curse yourself as you sink into a dentist’s chair and clutch on to an armrest for dear life.

For many of us, the taste of sugar is a bittersweet blend of euphoria and shame. If you struggle with dessert dependency, or if you’re one of the 29 million Americans with diabetes, we’ve written this article for you.

Beyond weight gain and tooth pain, sugar intake has been linked to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Recent science suggests that a high-sugar diet can complicate, and even cause, certain forms of cancer.

Sugar cane, corn syrup, honey — which is the worst? Which, if any, is actually good for you? In this two-part series on sugar, we’ll explore natural sweeteners as well as a few artificial alternatives, then offer some advice for sugar addicts.

Sugar Sources

Sugar is a vital part of life. Your body breaks down carbohydrates into sugars in order to make energy. We track the sugar inside of our bodies with a blood glucose level, which can be measured with a lab test or a personal glucometer.

When we talk about sugar, we’re usually talking about the direct form — not carbohydrates that break down inside of our bodies. Think of a nutrition label. The sugar section, measured in grams, can come from a variety of natural sweeteners. There’s no “% Daily Value” for sugar because the government hasn’t made any recommendations. The American Heart Association stepped in to give us some guidelines: nine teaspoons a day for men, six for women.

A can of Coca Cola has 33 grams of sugar. Since there are 4 grams of sugar in teaspoon, you’re slurping down eight teaspoons of sugar with each Coke — more than a whole day’s worth for women. Pepsi packs 41 grams in a can.

Don’t start enforcing teaspoon limits on yourself. That kind of thing usually doesn’t stick anyway. But you should read labels to see how much sugar you’re swallowing (here’s an online search tool). Look out for natural foods with hidden sweeteners: Instant oatmeal, for example, gets its kick from added sugars, not natural flavors.

Let’s pause here to clarify something. The American Heart Association guidelines only pertain to added sugars, not sugars that are naturally occurring in foods like fruit or milk. Added sugars are not artificial sugars — they are natural sugars that are added to foods in which they are not normally found, like instant oatmeal, either to improve or preserve flavor.

Added sugars come from a range of plants and crops. A traditional source is sugar cane, a tropical plant with tall green stalks. When harvested, the cane is shredded and its juices are stamped out and boiled into a thick mixture, which is crystallized in large tanks. Raw cane sugar is then separated from molasses, a dark brown syrup that can also be consumed.

At that point, the raw sugar can be refined and granulated into white sugar, commonly known as table sugar. Brown sugar is made by adding the molasses back in, which is why it’s relatively thick (light brown sugar is lighter because it has less molasses). Besides thickness, molasses offers calcium, potassium, and antioxidants, but that stuff doesn’t make the sugar function any differently in your body.

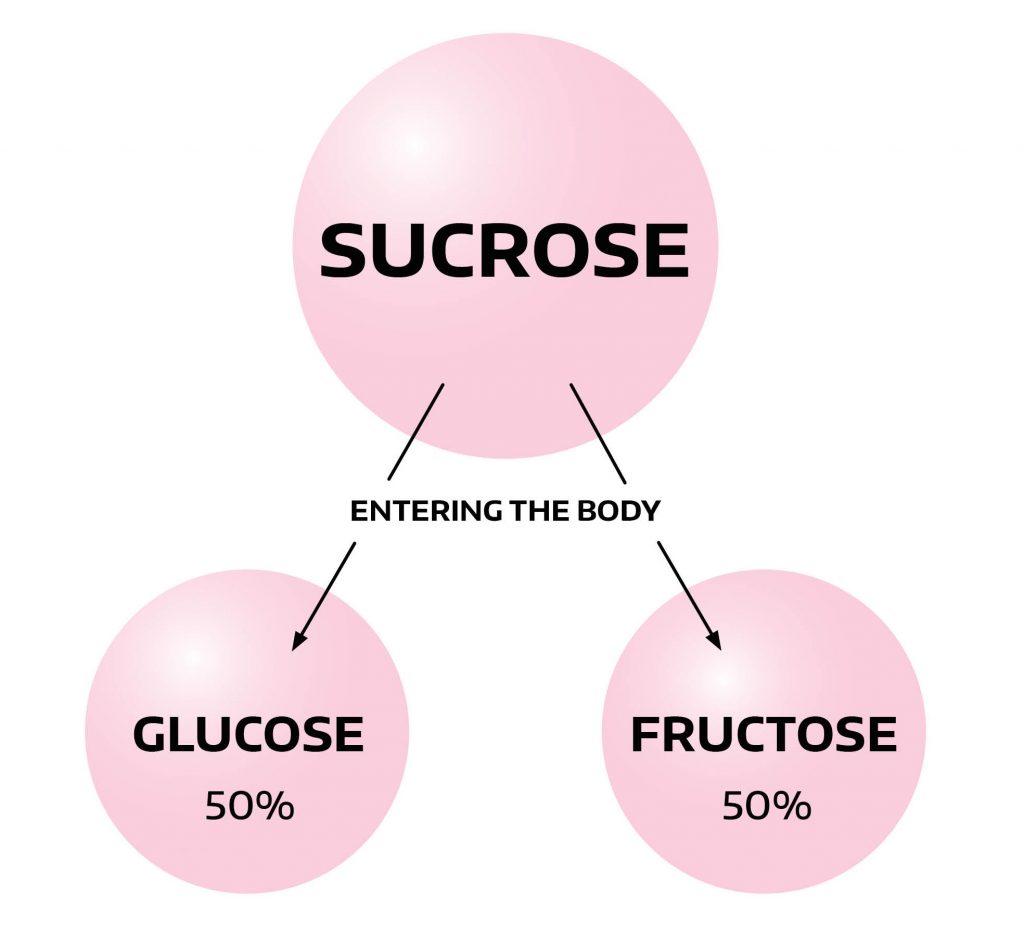

Sugar that comes from sugar cane plants is called sucrose. When sucrose enters the body, it breaks down into two other forms of sugar: glucose and fructose. You can find pure forms of fructose in honey, fruits, and vegetables, and you can produce glucose from starches like corn or potatoes.

Glucose became a major product in the late 1800’s because starches were grown throughout the U.S., rather than confined to the southeast or imported from the tropics like sugar cane. The liquid form of glucose, common in baking products and snacks, is corn syrup.

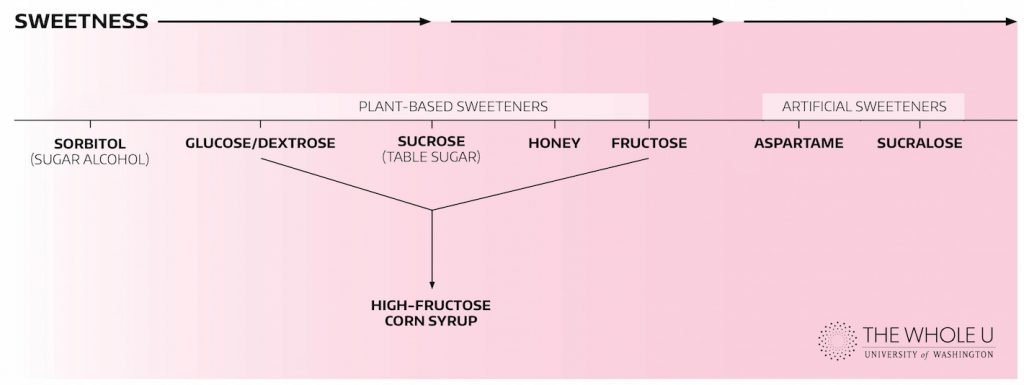

From a consumer standpoint, the downside of glucose is that it’s not as sweet as sucrose or fructose (see chart below). Scientists eventually found a way to change this by converting a half of the glucose molecules to the much-sweeter fructose. The result, high-fructose corn syrup, tastes similar to sucrose. A popular blend called HFCS 55 consists of 55% fructose.

By the 1980s, major soda companies had adopted the locally produced cane substitute. HFCS has since found its way into every aisle of the grocery store, sneaking into bottled drinks, condiments, cereals, crackers, and frozen dinners.

The ‘Healthiest’ Sugar

In addition to sugar cane and corn syrup, natural sweeteners can be made from beets, dates, grains, honey, maple syrup, agave nectar, coconuts, and even palm tree sap. All of these sugars contain either glucose, fructose, or both.

Which one should we eat — if any? First, remember that this is an industry. Economics and politics flow through each and every sweetener. Over the years, cane sugar companies have pitched their sucrose products as a healthy energy booster (same goes for glucose producers), and locally grown beet sugar was marketed as a patriotic product. From 2011 to 2015, sugar groups and corn syrup producers sued each other for billions over advertising claims.

On the other side of the issue, fad diets often denounce sugar as demonic.

The critical question is what happens when glucose and fructose enter our bodies. “Virtually every cell in the body can use glucose for energy,” writes Patrick J. Skerrett, the former executive editor of Harvard Health. “In contrast, only liver cells break down fructose.”

Fructose produces triglyceride fats, which can harm the liver and build up plaque in your arteries. Eating too much of it can put you at risk for cardiovascular events, such as a stroke, and raise your cholesterol. That means a fructose-heavy diet could have the same effect as a diet filled with high-fat processed foods.

Researchers have also found that flooding the liver with fructose causes the pancreas to release excess insulin. Some cancer cells appear to have receptors for these insulin signals, allowing the tumor to consume the sugar — which could help the cancer spread.

Back to the basics for a second: Every form of sugar, including glucose, will store as fat if it’s not burned, and obesity increases your chance of cancer. Still, high-fructose corn syrup suffers most of the blame in the court of public opinion, and it’s a fact that rates of obesity and diabetes have ballooned over the past 50 years — along with the spread of HCFS 55. But cane-sugar products also tend to be highly processed, and like sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup consists of a mix of glucose and fructose.

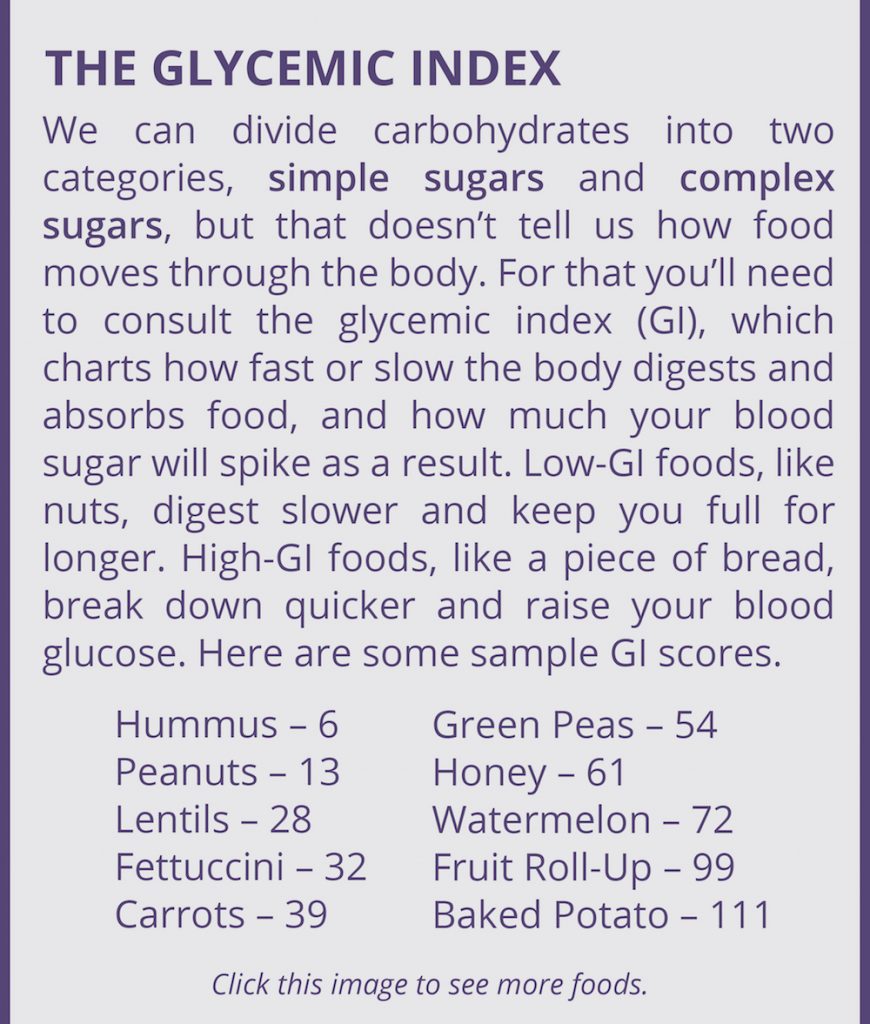

One chemical difference is that the molecules in high-fructose corn syrup are not bonded together like they are with sucrose. As a result, some research has suggested that those sugars might absorb into your bloodstream quicker. That matters because slow-absorbing foods can give you energy over time — instead of right away — and burn off easier.

On the glycemic index, which predicts how fast the body digests and absorbs food, pure fructose scores better than sucrose and glucose. For all its other faults, fructose won’t spike your blood sugar as much as other forms of sugar. But the same can’t be said for high-fructose corn syrup, since it’s a processed blend of glucose and fructose.

Why not play it safe and ditch fructose altogether? It’s not that simple. Remember, fructose isn’t just in high-fructose corn syrup. It’s also in sucrose, honey, agave, and fruit — and isn’t fruit supposed to be healthy? After all, a 2015 Gallup poll found that half of Americans actively try to avoid sugar, but a mere 1% of us try to avoid fruit.

Our views on sugar and fruit may be contradictory, but they’re based on something rational. Fruit has sugar, but it also has fiber that slows the release of that sugar in the bloodstream, plus a bunch of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. That’s why you should opt for an orange instead of a handful of orange Starbursts. Finally, when compared to processed sweets, fruit is relatively low-calorie and only has one ingredient.

Even still, some die-hard opponents of sugar have sworn off fruit. Other people embrace it as a satiating alternative to processed products. You’ll need to decide how it fits into your lifestyle.

Agave and honey tend to be fructose-dominant — sometimes as high as 70% fructose, 30% sucrose — but the range varies depending on quality. Like fruit, the sugars in agave and honey come with other nutrients, and since they’re sweeter, you can satiate yourself with less of it (1 teaspoon of honey might do what 2 teaspoons of glucose or 1.5 teaspoons of sucrose can do).

One study found a drop in weight gain and insulin levels in mice that were fed with agave instead of sucrose. But that’s just one study, and cross-species experiments only offer broad predictions about how the human body works. Also, keep in mind that agave and honey are often highly processed, which strips them of their nutrients.

At the End of the Meal, Sugar is Sugar

Whether it’s sucrose, glucose, or fructose, all natural sweeteners will boost your blood sugar to varying degrees and potentially store in the body as fat. So what can we do about it? In general, it’s better to treat your sweet tooth with a nutrient-dense dish — not a straight shot of sugar. Yogurt and a handful of dates are better than Sour Patch Kids and a Slurpee. Choose real strawberries and cream instead of the Starbucks Frappuccino. You get the point.

How do you know if your sugars will store as fat? The basic equation of gaining or losing weight is simple: When you consume more calories than you burn, you gain weight, and when you burn more than you consume, you lose weight. You can track an association (but not a strict causation) between sugar and your weight by logging your meals and hitting the scale each day.

If every type of sugar stores as fat if it’s not burned off, why not switch to sugar-free sweeteners? More about that in the Part Two: Artificial Sugars, which will run on Friday, Aug. 19.

If you have diabetes or prediabetes, consult your doctor or a nutritionist for specific questions. This article provides an overview of natural sweeteners, not a prescriptive guide to sugar consumption.

2 Thoughts on “Satisfy Your Sweet Tooth: Natural Sugars”

On August 12, 2016 at 6:00 AM, Tom said:

No mention of Xylitol and all the health benefits claimed in its name.

On August 12, 2016 at 1:04 PM, Quinn Russell Brown said:

Hi Tom,

While Xylitol is technically a natural sugar, we will cover sugar alcohols along with artificial sugars in part two of this series. Stay tuned!

Comments are closed.