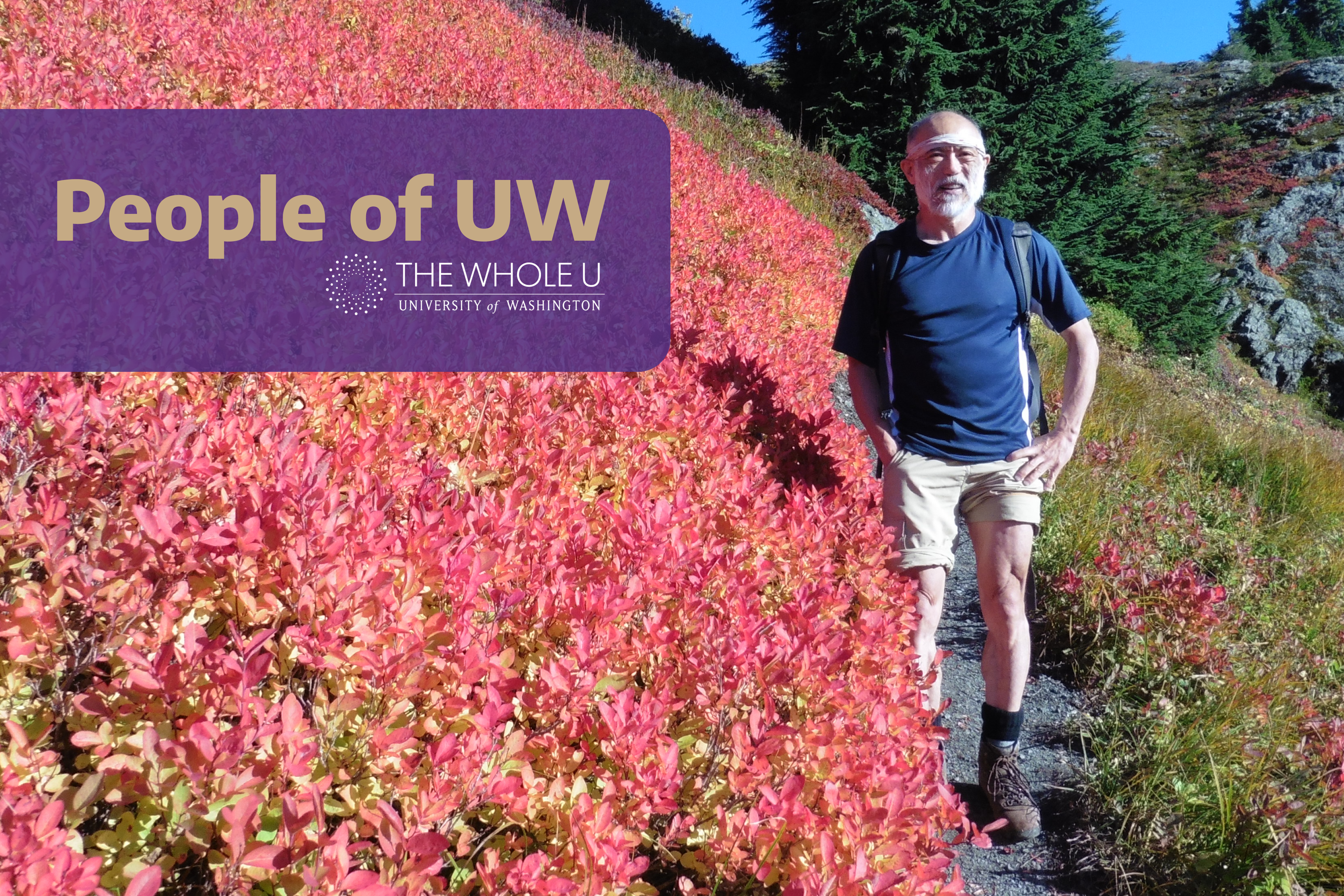

Meet Leo Egashira, the Optimistic Bearded Elder on a Bike

Leo Egashira is a man of many interests and pursuits. Talking to him, the word multipotentialite – a fancy new term for an old idea, of the polymath or Renaissance person – comes to mind.

The research coordinator with UW’s Indigenous Wellness Research Institute celebrates his 68th birthday this month, but he has no plans to slow down anytime soon. Retire? Eventually.

“Leo is a superstar,” said friend and colleague Bethany Hamamoto Robinson, a DEI Inclusion Analyst with UWHR.

Take his commitment to being carless, a decision made nearly 20 years ago. After his trusty Nissan Maxima’s transmission failed in 2003, Leo never looked back. He started biking upwards of 75 miles a week around Seattle’s notorious hills – rain or shine, every day.

“I ride my bikes to death,” he said. “When I take them in for major service the shop owner tells me it’s cheaper to buy a new bike.”

And when the pandemic obliged him to work from home, interrupting his daily commute, Leo nonetheless regularly hopped on his KONA bike – made locally in Ferndale, Washington – for exercise.

“I’ve never belonged to a gym,” he said. “I’ve never had to.”

Leo at Amabilis Mountain, East of Snoqualmie Pass, during a cross-country skiing trip in February 2022 / Courtesy Leo Egashira

Leo is also an avid hiker and backpacker, well into his fifth decade of the activity. He averages two trips a year to remote corners of North America, sometimes traveling solo, carrying a gear pack of 50 or more pounds.

A memorable hiking trip to Newfoundland required a Visa for entry to the tiny islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, a self-governing French territory of some 6,000 people on 93 square miles. Just 45 minutes off the mainland by ferry, Leo nonetheless had to find a guichet automatique (ATM) to withdraw Euros for his cash B&B payment.

This spring, he’s headed to Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument in Utah to hike the slot canyons – some so narrow even a day pack is too big to fit through.

In the winter months it’s cross-country skiing and snow-shoeing, naturally. And the occasional game of bridge.

There’s his enthusiasm for foreign languages. Fluent in Japanese, Leo also speaks “tourist Chinese,” has studied linguistics and is a strong advocate for the recovery and retention of indigenous languages.

He’s unquestionably passionate about experiencing the world. Leo’s first act after graduating from Harvard with a degree in East Asian Languages was to spend a year in Japan, teaching English and studying Japanese – immediately followed by six months in Taiwan, where he had lived for two years as a child, to practice his Chinese.

Leo lived in the Bay Area for four years while pursuing his MBA at UC Berkeley. While the training he received at Berkeley would prove valuable later in his career, at the time the South of Market scene in San Francisco held more appeal.

Incidentally, Leo has worn a full beard since 1972, a choice considered unusual – even eccentric – for a Japanese man in many Asian countries. He recalls being stared at on public transportation and once asked if he was Mongolian.

Since those early traveling days, there have been dozens of trips, both overseas and in North America. Leo has been to 49 of the 50 U.S. states, with just Kansas awaiting his visit. He was a mere 90-minute drive away on a recent trip, but, he says, he found no compelling reason at the time to make the effort.

“Maybe if Kansas had a ‘Wizard of Oz’ museum,” he said. “I would have gone for that.”

Centering identity

Leo is especially passionate about centering identity – his own, and the identities of those, like himself, who identify as both BIPOC and LGBTQIA.

As the child of an issei (first generation) mother and nisei (second generation) father, Leo considers himself more closely aligned with the sansei, or third, generation of Japanese Americans, though he jokes that he’s a “2.5”, halfway between nisei and sansei.

Leo’s parents met and married in Japan during World War II, during which time they both endured wartime hardships: food rationing, air raids, and rampant tuberculosis, among other things. As a U.S. citizen, Leo’s father held “enemy citizenship” and had a difficult time bringing his new bride home to Seattle.

Stateside, all of Leo’s extended family members were placed in internment camps.

The oldest of nine siblings, Leo spoke Japanese as his native language and taught himself English by watching American TV and listening to other kids.

A dedicated Catholic since childhood – with perhaps a hiccup here or there – Leo has become increasingly involved in faith-based LGBTQIA advocacy, serving on the board of directors for Dignity USA, a national gay and lesbian Roman Catholic civil rights organization, and for Generations Aging with Pride, a Seattle advocacy organization for LGBTQIA seniors.

His mid-career path led to self-employment as an export broker for the Japanese housing market. Then, the Japanese recession hit in the early 2000s. Clients went bankrupt, and Leo found himself scrambling.

“I went from self-employed to self-under-employed to self-unemployed very quickly,” he said.

So, at a time when many might start planning for retirement, Leo, then 55, jumped into an entirely new field: coordinating research into health disparities among Native Americans and piloting resilience-based interventions in Indigenous communities with the UW Indigenous Wellness Research Institute (IWRI).

Championing Indigenous public health

As a research coordinator for both the IWRI and Seven Directions, a Center for Indigenous Public Health, Leo focuses his prodigious energy on increasing public health capacity in Indigenous communities, including projects in opioid overdose prevention and elderly fall prevention.

“I was extraordinarily grateful to be given the opportunity,” he said. “There was a huge learning curve.”

Seven Directions is the first national public health institute to focus entirely on Indigenous health and wellness. It is housed in the Center for the Study of Health & Risk Behaviors in the UW Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences.

The work is rewarding, Leo says, because it affords him the opportunity to visit Indigenous community partners throughout the U.S., addressing health inequities in underserved populations.

The ‘eccentric’ beard of Leo’s youth, coupled with his balding head and the fact that he is not white, lend him credibility as an advocate and educator. Many in these Indigenous communities treat him with the respect accorded to an elder.

And when they learn of his family’s incarceration in Japanese internment camps, many of which were relegated to desolate, unproductive parts of the country – just as tribal lands have been – the sense of shared experience is profoundly reinforced.

Grateful for each year

Leo was diagnosed with HIV in 1992, the same year his partner, Joseph, died from complications. For 30 years, he has lived with a disease with no known cure, participating in many clinical research trials, riding his bike, faithfully taking his antiretroviral medications and staying hopeful.

What used to be an intense regimen of 20 antiretroviral pills per day has become, thanks to advances in HIV research, just one pill each day. Optimistic news about new cure strategies and a universal HIV vaccine are reported in the media frequently and there is hope that a cure might be just a few years away.

Leo doesn’t have any specific plans for his birthday – he’s not a big birthday guy. However, another birthday means another year of living, of engaging his many interests and using his energy to make the world a better, more hopeful place.

“I’m grateful,” he said. “To live this long, to be around for another year, and for living a fulfilling life.”

Happy birthday, Leo.

One Thought on “Meet Leo Egashira, the Optimistic Bearded Elder on a Bike”

On April 27, 2022 at 11:03 AM, Kiyomi Taguchi said:

Thank you for this wonderful portrait. I’m inspired by people who buck trends, follow their own course, and I especially love seeing the complexity of people’s identities, wonderfully eccentric and familiar at the same time. I hope to run. into Leo someday!

Comments are closed.