Satisfy Your Sweet Tooth: Alternative Sugars

In the first article of this two-part series on sugar, we looked at the history and science of natural sweeteners. Sugar is an energy source, so it burns off easily in moderate doses — less than 10 teaspoons a day, says the American Heart Association — but most of us consume way more than that. This surplus sugar often sticks around in our bodies, enlisting in the fat reserves instead of the energy infantry.

What if we could stop sugar from sticking around? What if we could satisfy our sweet teeth without inflating our waists, spiking our blood sugar, and disappointing our dentists? That’s the sales pitch for sugar alcohols and artificial sugars.

From “sugar-free” to “zero-calorie,” alternative sweeteners promise all of the taste and none of the toothache. Whether they deliver on the taste part is a personal preference, but the safety of these sugar substitutes is guided by science… right? That’s what the government says, but many of us are suspicious. To find out for ourselves, let’s dive into the fizzy history of pseudosweetness.

The Known Unknown

Citing hundreds of toxicological trials and clinical studies, the FDA has approved six different high-intensity sweeteners for human consumption. Aspartame and sucralose in particular are two of the world’s most researched food additives. That sounds pretty conclusive, so what’s the fuss about?

For one, these sweeteners have shady backstories. As you’ll read below, GMO-giant Monsanto stars alongside former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in the history of aspartame. And even the most careless consumer would raise an eyebrow at how fast synthetic sugars were rushed to market by big pharmaceutical companies, often before adequate testing.

While extensive research has ruled out the risk of certain ailments, like liver damage or bladder cancer, new studies continue to link sugar substitutes to health problems. Loud voices and passionate stakeholders can further complicate things: Should we trust weightlifting websites, or parenting blogs? Soda companies, or government scientists?

Another reason for the mystery is time. We can track weight gain and dental damage over weeks and months, but diseases like cancer develop over years or even decades. In that case scientists can only make predictions, often using lab mice instead of humans, so take the results with a grain of sucrose. Or sucralose. It’s up to you.

Weighing the Risk

Aspartame and sucralose are called non-nutritive sweeteners because they aren’t metabolized like regular sugars (they’re not digested and stored, only excreted). Since they add taste without adding sugar — or in some cases even calories — these sweeteners could be a godsend for people living with obesity or diabetes. Now for the scary stuff.

Increased hunger

By whetting your appetite but not consuming any nutrients, you might be inciting a process that leads to weight gain. Think about it: You may be tricking your tongue, but your body still wants energy, and artificial sugars don’t provide any. The result? You could be hungrier — not fuller — than before.

Cardiovascular health and diabetes

Diet soda drinkers have also been linked to cardiovascular issues, but that demographic may tend to be more at risk for such events in the first place. As for diabetes, a popular study found that artificial sugars may throw off the body’s ability to control glucose, which could actually cause the condition. Researchers saw higher blood glucose levels in mice fed with aspartame and sucralose than those fed with sugar water.

Gut health

The same study, which also looked at human subjects, suggested that sugar substitutes could alter the bacteria in our gut (the sugars aren’t digested, but they still pass through). That said, our gut cells turn over every week, and the gastrointestinal tract is known for its resilience. The longterm affects of these sweeteners on our gut bacteria? They’re unknown — and we’re the lab rats.

Cancer

Last comes the scariest question about artificial sugars: What if they cause cancer? It’s always possible, but there’s currently no robust evidence for it, according to the American Cancer Society.

Yes, there a few alarming studies, some of which have come under international scrutiny. In 2006, the Ramazzini Institute in Italy noticed an increase in leukemia and lymphoma in rats that were fed huge doses of aspartame.

After reviewing the research, the European Union’s Food Safety Authority determined that many of the rats likely died from an infection, not aspartame, and that the rest were killed not by the sweetener itself but by the sheer size of the dose. Further scrutiny caused more concern about the institute: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency found that Ramazzini researchers couldn’t even correctly identify cancer cells in 22 out of 23 samples.

This year, the institute published a study linking sucralose to leukemia (the results were widely criticized when presented at a conference in 2012). Their findings have yet to be replicated in other labs, which is a core principle of science.

Your Call to Make

Our dietary choices should be viewed in context. The question isn’t whether diet soda is bad for you, but whether diet soda is worse than what you would drink otherwise. As we learned last week, eating too much natural sugar can create a pathway to cardiovascular illness and cancer. If you’re paranoid about getting leukemia from artificial sugars, it’s a bit ironic to slurp down 30 teaspoons of sucrose each day.

This article provides information, not a prescription. You know your body better than anyone else, and you should base your choices on your own life. If you have diabetes, you may decide that eating real sugar is worse for your immediate health than alternative sweeteners. If you’re not worried about your blood sugar, burning off the occasional can of Coke may be preferable to worrying about a future risk of gut damage.

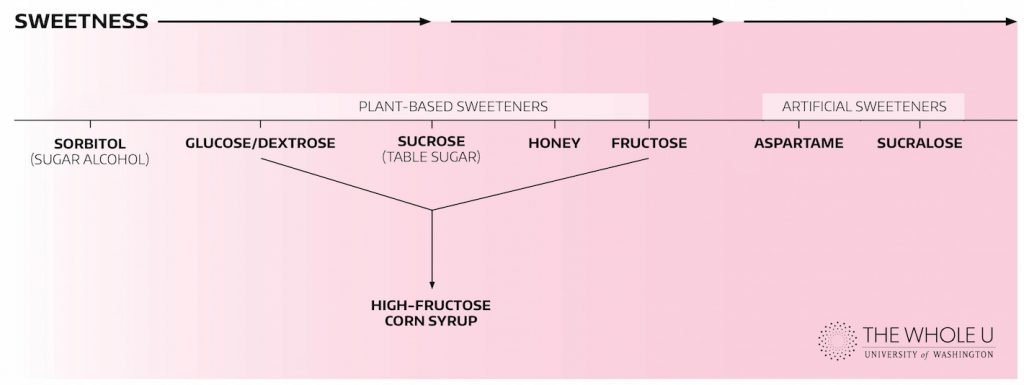

Now let’s take a closer look at sugar alcohols, aspartame, and sucralose. We’ll start by seeing where they land on last week’s sweetness graphic.

Sugar Alcohols

Found in: Chewing gum, toothpaste, candy, cookies

On a label: Sorbitol, xylitol, mannitol, maltitol, lactitol, erythritol, arabitol, glycerol

Compared to sucrose: 25% to 100% as sweet

Calories: Yes

Acceptable Daily Intake: N/A

Where it came from: No, sugar alcohols won’t get you tipsy, but their chemical makeup is similar to alcohol. They occur naturally in fruits or vegetables — from olives to asparagus — and they can be commercially manufactured from sugar. We grouped them with alternative sweeteners because they’re not as well-known or researched as other sugars.

Sugar alcohols carry half as many calories as sucrose, and they’re usually not as sweet. Because of their chemical makeup, they’re not fully broken down and absorbed by the body, but they still provide us with energy, making them a nutritive sweetener.

You can find sugar alcohols listed under the carbohydrate tab of a nutrition label, but the FDA hasn’t recommended a daily intake. Medical professionals warn that more than 10 to 15 grams a day can cause bloating, stomach pain, and even diarrhea.

If you’re a diabetic thirsting for a reliable sweetener, this might be it. Sugar alcohols don’t need insulin, and they won’t spike your blood sugar as much as natural sugars. Check out this UW Medicine guide about sweeteners for people with diabetes.

Because sugar alcohols aren’t broken down by the body, they won’t help plaque create cavities. Some dentists even encourage their patients to seek out xylitol, which has been linked to oral health. The Spry brand of gum and mints provides tasty doses of the sweetener. But some research has found that overdoing it could damage the teeth.

The FDA put together this sleek handout about sugar alcohols. But if you’re skeptical about information from the FDA — isn’t that, like, why we’re writing this article? — here’s a less flashy handout from Oregon State University. A crucial takeaway from the OSU guide: “Long-term benefits or risks have not been established.”

Aspartame

Found in: Diet Coke, Coke Zero, Diet Pepsi (starting again in September), Sugarfree Red Bull, Dannon Activia Light, blue packets of Equal and NutraSweet

On a label: Phenylalanine

Compared to sucrose: 60-200 times sweeter

Calories: Yes

Acceptable Daily Intake: 22.7 mg per pound of bodyweight

Where it came from: Aspartame was accidentally discovered by a chemist at a pharmaceutical company in the 1960s. Like many other people during that time period, he was up for experimenting, so he licked his finger while working on a treatment for ulcers. It was an odd combination of amino acids and methanol, but it tasted very, very good.

His bosses seized on the artificial sweetener, insisting they had run exhaustive tests to verify its safety. The FDA approved it in 1974, but a year later, new research suggested that it destroyed the livers of lab mice. The FDA put aspartame’s approval on hold.

The company found a new CEO, prominent Republican Donald Rumsfeld, and began selling aspartame overseas. By 1979, the FDA “found no evidence of toxicity, but … did not rule out the possibility that aspartame might cause brain tumors in rats,” writes Deborah Jean Warner in Sweet Stuff: An American History of Sweeteners from Sugar to Sucralose. The FDA commissioner wasn’t convinced.

Rumsfeld campaigned for Ronald Reagan in the 1980 presidential election and later served on his transition team. The next year a wave of anti-regulation swept the federal government, and aspartame got the green light from the FDA. By 1985, the company was purchased by Monsanto (it was later resold). The FDA now calls aspartame “one of the most exhaustively studied substances in the human food supply, with more than 100 studies supporting its safety.”

Still, the government has received thousands of health complaints ranging from headaches to seizures. If this happens to you, or if you experience any of the symptoms mentioned earlier, you should probably steer clear of synthetic sweeteners.

A common concern about aspartame is that the methanol is toxic when it enters our GI tract. But you can also find methanol in citrus fruits and tomatoes, says Dr. David G. Hattan, a toxicologist at the Department of Health and Human Services. Methanol from aspartame “is the same as from other sources,” Hattan wrote on Snopes.com, and “it is readily and naturally metabolized.”

Mercola, an alternative medicine news website, disagrees. The methanol in aspartame can lead to breast and prostate cancer, a narrator states in one of their videos about aspartame, but it doesn’t happen in non-human animals because their bodies can break it down into harmless acids. Hence, lab tests on mice couldn’t rule out this danger. This is not a mainstream view among health organizations.

How much aspartame are you drinking? The magazine Diabetes Self-Management has some answers. Diet Coke, for example, has 187.5 mg in each 12-ounce can. If you want to cut back, reach for a Coke Zero (87 mg) or a Sprite Zero (75 mg).

Either way, it’ll be hard to reach the FDA’s daily intake limit, which is 3,405 mg for a person who weighs 150 pounds. That’s 39 cans of Coke Zero. Sound like a lot? It’s actually 100 times less than the amount of aspartame believed to cause harm.

Sucralose

Found in: Gatorade Propel, Sparkling Ice, Sugarfree Red Bull, Log Cabin Sugar Free Syrup, PowerBar, yellow packets of Splenda

On a label: Sucralose

Compared to sucrose: 600 times sweeter

Calories: No

Acceptable Daily Intake: 2.2 mg per pound of bodyweight

Where it came from: Sucralose was also invented on accident. A group of chemists in London were experimenting with sugar (chemically known as C12H22O11) when they replaced three of its oxygen molecules with chlorine and created a calorie-free sweetener. Somehow, when you mix sugar with chlorine, it still tastes good — 600 times as good, to be exact. (Sound gross? You also ingest trace amounts of chlorine when you drink tap water.)

Sucralose sweetens a wide range of consumer products, but it became famous thanks to those yellow packets of Splenda. The company’s original slogan was “Made from sugar so it tastes like sugar.” An inevitable lawsuit made way for a less exciting replacement: “Starts with sugar, tastes like sugar, but is not sugar.”

Each packet has 12 mg of sucralose mixed with glucose fillers, so that one teaspoon of Splenda tastes similar to one teaspoon of sugar. Since it’s a very strong sweetener, the recommended daily intake is much lower than aspartame: 330 mg for a 150-pound person.

Sugarfree Red Bull has sucralose, aspartame and acesulfame K, a third artificial sweetener. Diet Mountain Dew also has all three. If you’re freaked out by synthetic sugars, you probably want to skip these drinks — assuming you don’t have an all-night video game tournament to attend.

The major health concerns about sucralose have been covered in earlier sections.

Full disclosure: This article was written under the influence of Red Bull, as well as Sugarfree Red Bull and Red Bull Total Zero. The author cannot say with certainty which flavor damaged his body the most. But, hey — he finished the article.

2 Thoughts on “Satisfy Your Sweet Tooth: Alternative Sugars”

On August 21, 2016 at 10:03 AM, sheryl said:

What is this website about – if it’s a portal to the UW please, use UW resources and oversight. I’m concerned the UW is giving credence to Mercola – ugh. Dangerous for public health. You are representing the UW Medical community. This is a guy who thinks vaccines are dangerous and that your body energy changes by walking barefoot on the earth – he makes millions of dollars selling supplements. Why not interview an expert on campus instead of relying on Mercola website? Though aspects of this article have merit, the conspiracy surrounding the FDA is not conducive to public health – there are issues with the FDA but the tone of this article is conspiratorial. The trend on this UW website overall is not science-based. I am concerned about overview by MDs – even web MD has websites reviewed by experts. Use your people – I’d much rather read a post by a UW physician, what is concerning them? There are metabolism researchers at the UW – what is their take on artificial sweeteners?

On August 22, 2016 at 10:47 AM, Quinn Russell Brown said:

Hi,

Author here. The Mercola mention is a tiny part of the article that I felt needed to be included. Mercola has a major presence on the internet and many of our readers will encounter it either way. I wanted to use this platform to educate them about what it is. Mercola is, according to my article, “an alternative medicine news website” whose positions “are not mainstream view[s] among health organizations.”

Prior to the Mercola mention, a source from the Department of Health & Human Services explains why mainstream science believes the Mercola view is wrong, and throughout the article we exclusively source mainstream medicine. We also mention the Ramazzini Institute. This is important because Mercola and the Ramazzini Institute are two of the loudest voices linking artificial sugar to cancer. I felt ignoring them would be disingenuous. I am a health writer, not a scientist: My goal was for this to be thorough and fair reporting, not a scientific journal.

Still, this article has not given shoddy science a platform; it’s actually the opposite. The reality is that people are skeptical of artificial sweeteners. This article empathizes with their skepticism but, ultimately, takes the side of established science. A mention of minority science — or fringe science, or pseudoscience — should not be interpreted as an endorsement.

Comments are closed.