Searching for ‘Moby-Dick’

Search for Moby-Dick in the UW library database, and you’ll see over 40,000 results. Restrict that search to books published in 1851, and you’ll see two.

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the one published in New York by Harper & Brothers is the first edition. This is, after all, a Great American Novel we’re talking about.

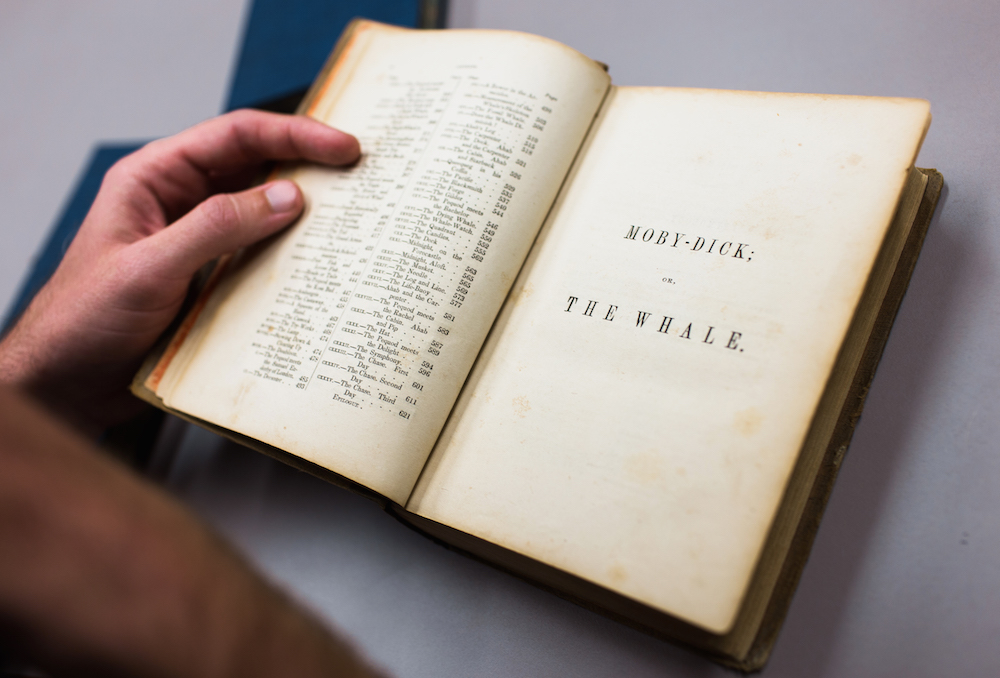

But the first people to read that famous opening line, “Call me Ishmael,” lived across the Atlantic in London. In November of 1851, a month before the American release, British publisher Richard Bentley released the book under the title The Whale. That’s the true first edition, and only 500 copies were printed.

One of those resides on campus, at the UW Libraries Special Collections.

My search for a first edition Moby-Dick began, like so many things, out of curiosity mixed with boredom. I didn’t necessarily need to read the book again; however, I searched the library database anyway, wondering just how many copies might sit in the stacks. But a library search isn’t an Amazon search, and I realized that some of the library copies were really, really old.

That realization led me to the basement of the Allen Library, where Special Collections stores most of its rare and archival material.

There I met with Sandra Kroupa, book arts and rare book curator, who curates 19th century American literature. Using funds from The Andrew and Frances Hilen Nineteenth Century Americana Endowment, left by a former UW English professor and his wife, Sandra purchased the London first edition of The Whale in the 1980s.

She also purchased a copy of the first American printing, the more famously titled Moby-Dick; or, the Whale.

Down in the library basement, I got a brief lesson on how to carefully handle antique books. I also safely stored my pen: stray ink has managed to mar more than one piece of the collection.

I was then free to flip through the 164-year-old pages of my favorite book. I searched for one passage that holds particular meaning for me:

“For now, since by many prolonged, repeated experiences, I have perceived that in all cases man must eventually lower, or at least shift, his conceit of attainable felicity; not placing it anywhere in the intellect or the fancy; but in the wife, the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fireside, the country.”

Searches mustn’t always be for a whale, of course. Sandra has also purchased first editions of other iconic works of American literature. Special Collections is home to The Scarlet Letter, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Little Women, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, and Walden, among others.

“I can give someone like you who loves the book the experience of holding it in your hand,” Sandra told me.

I first read Moby-Dick in 2012. Since then I’ve reread it, sometimes for wisdom, sometimes just to watch my bookmark slowly progress along the spine. I’ve followed the book on Twitter, and I’ve listened to Benedict Cumberbatch read it aloud. I’ve been known to buy the book simply for its cover. I’ve even purchased whale-themed home accessories.

When you love something you search for new and different ways to connect with it.

“Yes, a book’s ideas are important,” Sandra said, “but there’s something about the physical artifact and knowing what the book meant at the time it was printed.”

When it was first printed, however, Moby-Dick didn’t mean much to its British publisher.

“It was a dud,” Sandra told me.

In fact, when those first 500 copies were printed in London, they sold so poorly that some never left the printer. So the publisher waited two years, repackaged the unsold copies with a title page marked “1853,” and re-released the book in hopes of luring buyers looking for something “new.”

Sandra bought one of those for the collection, too — a first edition, published a second time.

The book didn’t sell well initially, but today a pristine first edition can fetch tens of thousands of dollars at auction. However, the copies in Special Collections are a little too well-loved to be considered pristine.

And Sandra is okay with that.

“Pristine books are really expensive, but they are pristine because nobody actually touched the book,” she said. “I think that’s kind of sad, actually. When I hold worn copies, I can picture myself in place of the original owner. It drops me down into history.”

After my visit with Sandra, I walked up the basement steps and out of the Allen Library. I had found my whale. In its 164 years, the book had crossed many hands and traveled an ocean. I had merely traveled across campus. Turns out, not every search is a struggle.

***

You can visit the Special Collections reference desk any time during its operating hours. But to see very rare books like Moby-Dick, make an appointment first, as these materials take advanced planning to retrieve. For more information, see the Special Collections hours and contact information.

Ryan Petersen works as a technical writer for UW Human Resources, where he doesn’t often write about antique books. He does hope, though, that the policy summary he wrote will one day be published as a collector’s edition.

Ryan Petersen works as a technical writer for UW Human Resources, where he doesn’t often write about antique books. He does hope, though, that the policy summary he wrote will one day be published as a collector’s edition.