Faculty Friday: Patricia Ebrey

If you’re interested in taking a whirlwind journey through thousands of years of Chinese history, but not keen on sacrificing scholarly attention to detail or a sound sense of storytelling, you’ll want Patricia Ebrey to be your guide.

A professor of history at the University of Washington, Ebrey has devoted more than four decades to illuminating the history of China for hundreds of thousands of readers. Her books give students a firm footing in China’s past at a time when the country is moving faster than ever into the future.

With high-speed rail lines and a bevy of other ambitious civil engineering projects, the China of today is a far cry from the country Ebrey remembers encountering during her first brief ten days’ visit in 1978 and again two years later during a three-month stay in Beijing, when China was just emerging from the Mao era.

“It has been amazing to watch the changes that have occurred in China since my first visits in 1978 and 1980,” she says. “No place in the world has changed as fast as China has in my lifetime.”

Such rapid change is not just limited to infrastructure.

Ebrey says new archaeological discoveries, more access to sources, more use of science in fields like environmental history, and more opportunities to collaborate internationally have the potential to “completely change the narrative” of Chinese history.

It all places Ebrey, the historian, in a unique position of being able to update her own widely read works to reflect such changes. This past December, she committed to revise her Cambridge Illustrated History of China, which covers all of Chinese history from the Neolithic period of 10,000 years ago to today.

She initially wrote the book in the mid 1990s for the general public, but it proved so accessible (and subsequently so popular), that is now regularly used as a textbook. Ebrey says it always feels good to meet people who tell her they used the book in class or that it was the first text they read on Chinese history.

“If, for the next 20 years, that can be the case, it’s worth taking the time to update it,” Ebrey says. Hers is a spirit of historical stewardship that finds its roots in one of those happy accidents of undergraduate course selection.

“I decided I wanted to be a college teacher before I decided what subject,” Ebrey says, recalling the story that set her on a trajectory to becoming one of the most widely read and respected historians in her field.

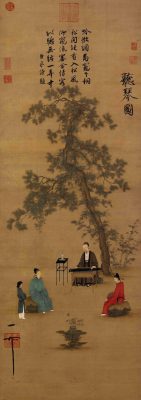

Besides being talented in music and poetry, Song Dynasty Emperor Huizong (r. 1100 to 1126) is considered among the best artists in Chinese history, earning a reputation for his achievements in calligraphy and painting.

As an undergraduate majoring in history at the University of Chicago, she was required to take a class on non-western civilization. Among the four choices of India, China, Japan, and Russia, Ebrey chose China. In high school, she had always enjoyed learning French, so she decided that if she was going to take a class on Chinese civilization, she might as well take Chinese language. It happened that the University of Chicago was an outlier at the time as the only institution to teach classical Chinese before students progressed to learn the modern language.

“You were starting with real texts that the literate elite of China had memorized,” Ebrey recalls. “This was a very different way to teach and learn it, but I found it very appealing and interesting so I stuck with it.”

After finishing her undergraduate degree, Ebrey started graduate work at Columbia University. Shortly thereafter, the Vietnam War ended, causing enrollment in Asian Studies classes to drop, which in turn meant there weren’t nearly as many jobs as there had been in years prior. But Ebrey says she felt too invested in her research to be discouraged.

“[Once] you get into something, it’s natural that people say, I’ve put in all this time already, [so] I’m going to stick with it,” she says. So she did—embarking on a dissertation that traced the fortunes of one family of elite status over a period of more than 900 years beginning around 0 AD.

“One reason I ended up picking China was realizing there were so many big questions that people hadn’t worked on yet,” Ebrey says. “In a Western civilization class, somebody could do a dissertation on orphanages in southern France from 1780-1800, but with China, people were doing big topics because they hadn’t been done yet.”

For the last four decades, Ebrey has focused on the Song Dynasty (960–1279): three centuries marked by sustained economic growth, technological innovations, and a flourishing of literature and the arts that gave birth to moveable type, paper money, water-powered mechanical clocks, gunpowder, the use of coal as fuel, and an expansion of foreign trade that made China the most advanced country in the world. Printing led to the survival of many more sources, making it possible to do research on a much wider range of topics, including topics like the lives of women.

If the scope and depth of Chinese history feels daunting, Ebrey says there’s “really no right or wrong answer” about where to start reading about it. Some surveys of Chinese history begin with “oracle bones”—remnants of bovine shoulder blades and tortoise shells that were used by elites in ancient times to communicate with dead ancestors and divine their wishes.

“You would heat it and get a crack and, depending on the direction the crack, you get a yes or no answer,” Ebrey says, explaining how the process served as a means of using ancestors as intermediaries to the gods who could intercede on your behalf or find out what the gods want. “These were often then inscribed as part of record-keeping.”

Ebrey will discuss how this practice by powerful members of ancient Chinese society spread and shaped the everyday life of ordinary people for many centuries in a February 5 lecture, “Death and the Ancestors: The Religion of the Family in China,” part of the Department of History’s winter lecture series, “Life, Death, and the Gods.”

“…the book is a supreme example of meticulous scholarship and eloquence.” —The Spectator

The lecture will reflect Ebrey’s ability to move easily between time periods and topics throughout her distinguished career.

Perhaps the most telling examples of Ebrey’s talents as an historian can be found in her critically-acclaimed eponymous biography of Song Dynasty Emperor Huizong (1085-1135), one of China’s greatest and most gifted emperors who excelled as a calligrapher, poet, painter, and a pioneer in the collection of art and antiquities.

But his accomplishments as a patron of arts, architecture, music, medicine, and Daoism are often occluded by his tragic end—spending the final eight years of his life as a captive of the invading Jurchens.

“Most who have heard of Huizong know him as a ruler talented at painting and calligraphy but inept at selecting advisers and overly self-indulgent,” Ebrey told UW News at the time of the book’s publication.

“Chinese historians have traditionally assessed Huizong’s reign with its end in mind; since Huizong’s government came to a bad end, he must have been at fault. I hope my book will convince people that it is time to set aside that way of thinking. I think that viewing the world from one person’s perspective is an excellent way to get into an age and a place.”

There can be little doubt that Ebrey’s own historical perspective will continue to open portals to the past for countless multitudes for many years to come.

Get tickets to Patricia Ebrey’s February 5 lecture, “Death and the Ancestors: The Religion of the Family in China” here.